Classification of Prostatitis Syndrome

The diagnosis of symptomatic prostatitis refers to a variety of entities which may be related to infection and inflammation of the prostate gland (bacterial prostatitis), inflammatory and non-inflammatory chronic pelvic pain syndrome, and pelvic pain not related to prostatitis.

Clinical Diagnostics

In acute bacterial prostatitis, clinical symptoms are typical. Infection is defined by midstream urine analysis. In CBP, the key point of diagnosis is the use of a 2-glass test, with or without additional ejaculate analysis. The same test is used to define or exclude inflammation and / or infection in CPPS. In CPPS, symptomatic evaluation is based on a validated NIH-CPSI questionnaire. Additional phenotyping may be helpful in characterizing the predominant symptoms.

Therapy

Antibiotics surely play a fundamental role in bacterial prostatitis therapy. They should be introduced empirically in acute prostatitis with a high intravenous dose and always guided by resistance determination in chronic cases. Thanks to their pharmacokinetic properties and antimicrobial spectrum, fluoroquinolones remain the most highly recommended antibiotics. The most appropriate treatment for chronic pelvic pain syndrome is a multimodal approach based on phenotyping including alpha-blockers, antibiotics, anti-inflammatory medication, hormonal therapy, phytotherapy, antispasmotics and non-drug-related strategies, such as psychotherapy and attempts to improve relaxation of the pelvic floor. The response can be evaluated by a drop in symptoms, using the scoring of the NIH-CPSI.

Diagnosis of prostatitis refers to a variety of inflammatory and non-inflammatory, symptomatic and non-symptomatic entities often not affecting the prostate gland. Prostatitis syndrome has been classified in a consensus process as infectious disease (acute and chronic), chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CPPS) and asymptomatic prostatitis [1] (Table 1). Prostatitis-like symptoms, especially pelvic pain, occur with a prevalence of about 8% [2], with severe symptoms especially in CPPS. The National Institutes of Health Chronic Prostatitis Syndrome Index (NIH-CPSI) represents world-wide the validated assessment tool for evaluating prostatitis-like symptoms [3] and [4]. Only Category IV prostatitis is asymptomatic with the diagnosis normally resulting from histological evaluation by biopsy [4].

Table 1

NIH classification system for prostatitis syndromes [1]

| Category | Nomenclature |

|---|---|

| I | Acute bacterial prostatitis |

| II | Chronic bacterial prostatitis |

| III | Chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CPPS) |

| III A | Inflammatory |

| III B | Non-inflammatory |

| IV | Asymptomatic prostatitis |

In clinical practice, 90 percent of outpatients suffer from CPPS, inflammatory or non-inflammatory disease [5] and [6]. Management of pelvic pain is a major challenge for the urologist [5]. Men with proven bacterial prostatitis need meticulous diagnostic management and therapy, some of them have to be hospitalized [6], [7], [8], [9], and [10].

This review covers accepted aspects of diagnostic procedures and therapeutic attempts in men suffering from symptomatic prostatitis and CPPS (Categories I to III).

Careful medical history (e.g. physical examination) investigating presence of fever and voiding dysfunction is fundamental. It should include scrotal evaluation and a gentle digital rectal examination without prostate massage, which is not recommended due to the risk of bacterial dissemination. The prostate is usually described as tender and swollen [6], [7], [8], and [9].

Diagnosis is based on microscopic analysis of a midstream urine specimen with evidence of leucocytes and confirmed by a microbiological culture, which is mandatory and the only laboratory examination required [7], [10], and [11]. Enterobacteriaceae, especially E. coli, are most common (Table 2) [6], [7], and [11]. Prostatic specific antigen is often increased and may be used diagnostically [7] and [9].

Table 2

Common pathogens in bacterial prostatitis (NIH I, II) [6] and [11]

| Etiologically recognized pathogens | Microorganisms of debatable significance | Fastidious microorganisms |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | Staphylococci | M. tuberculosis |

| Klebsiella sp. | Streptococci | Candida sp. |

| Proteus mirabilis | Corynebacterium sp. |

|

| Enterococcus faecalis | C. trachomatis |

|

| P. aeruginosa | U. urealyticum |

|

|

|

M. hominis |

|

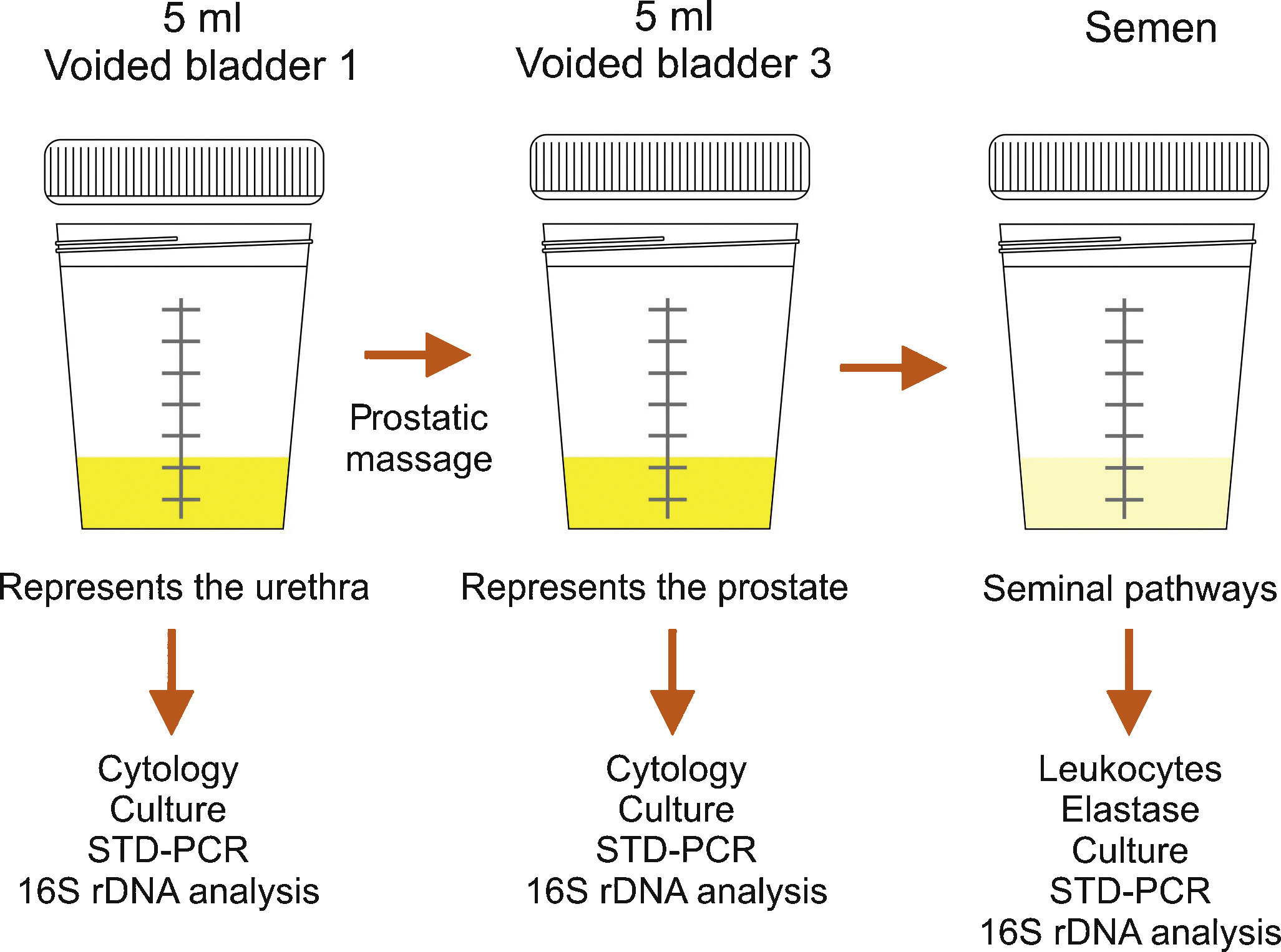

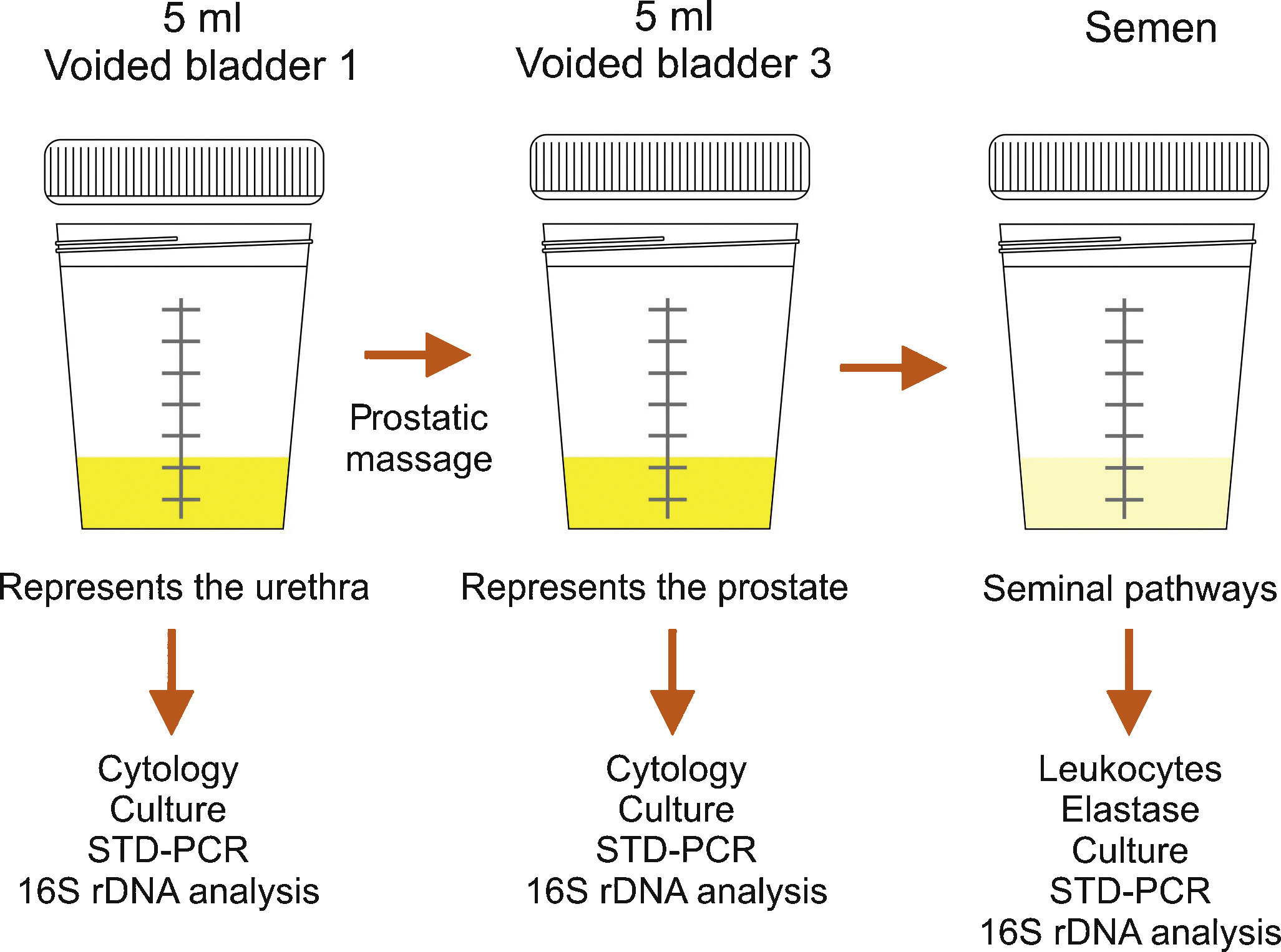

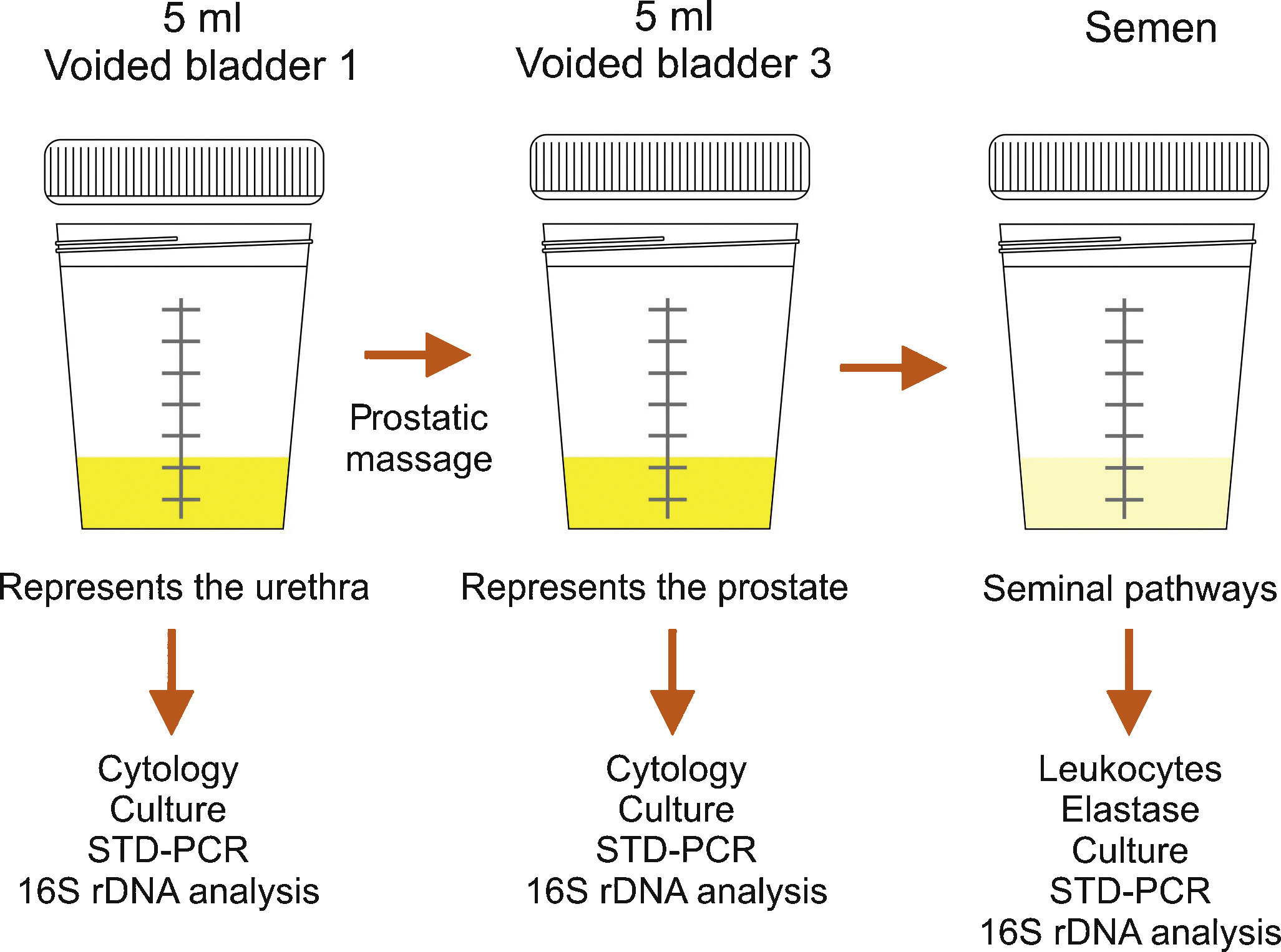

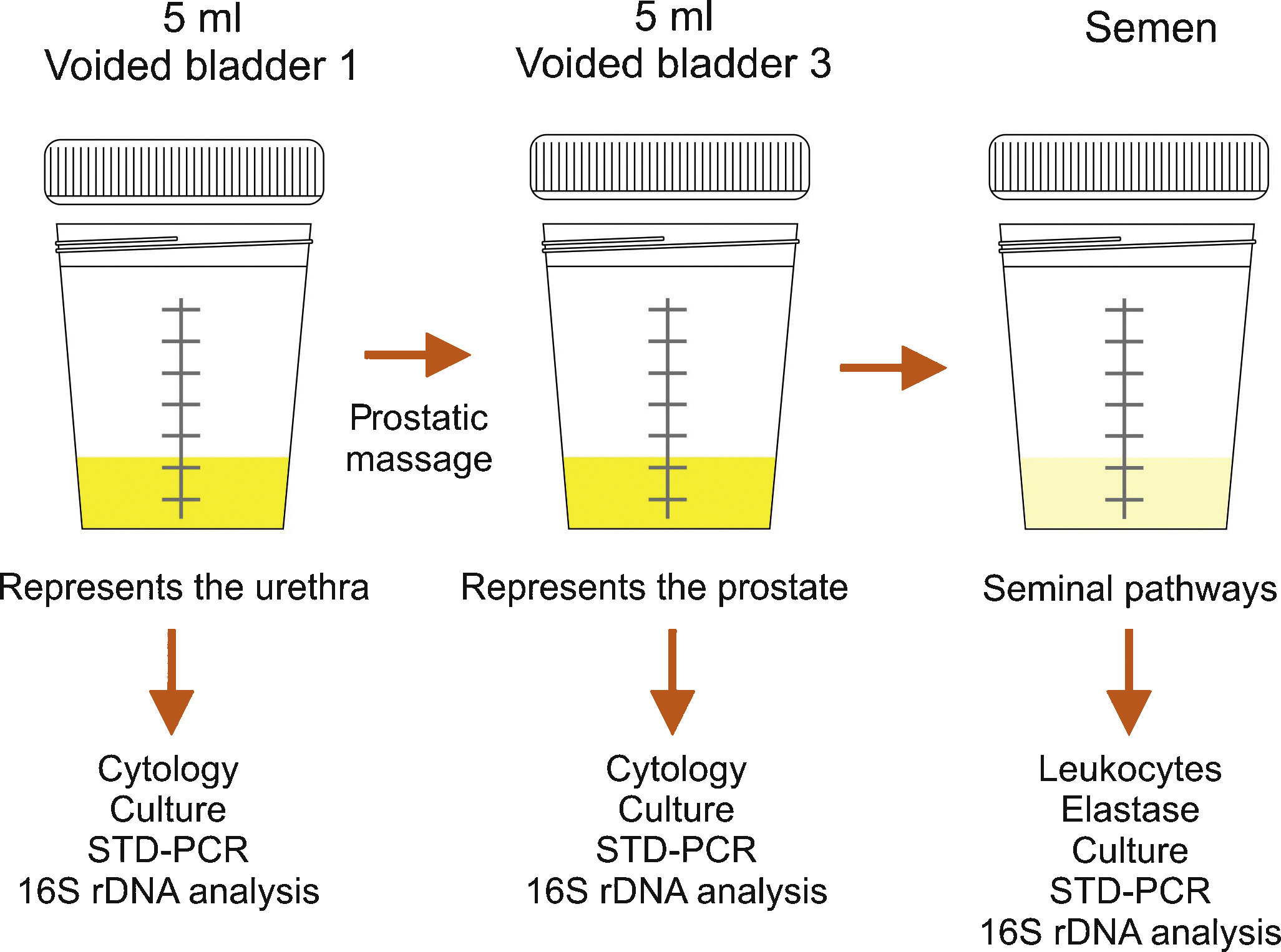

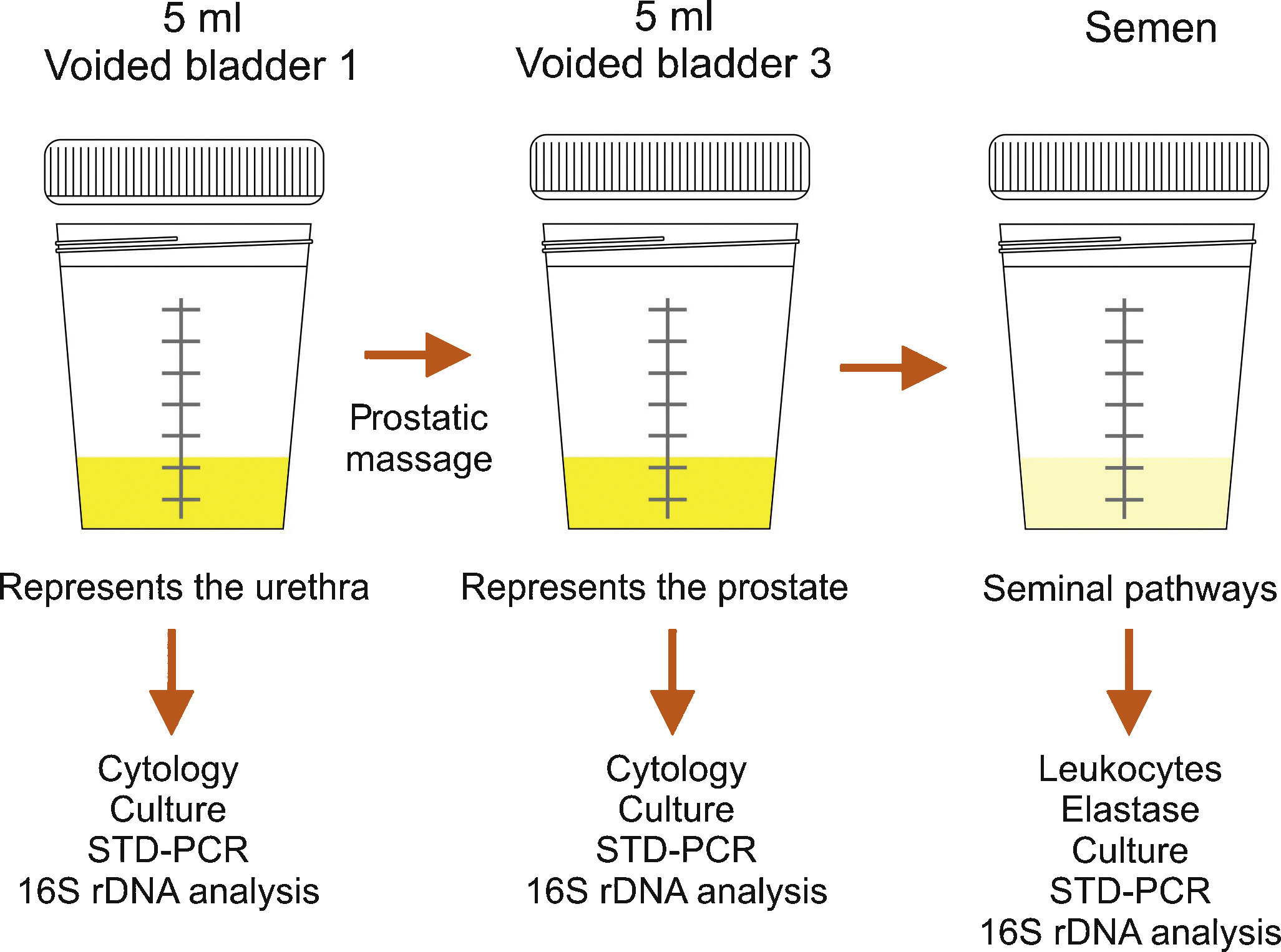

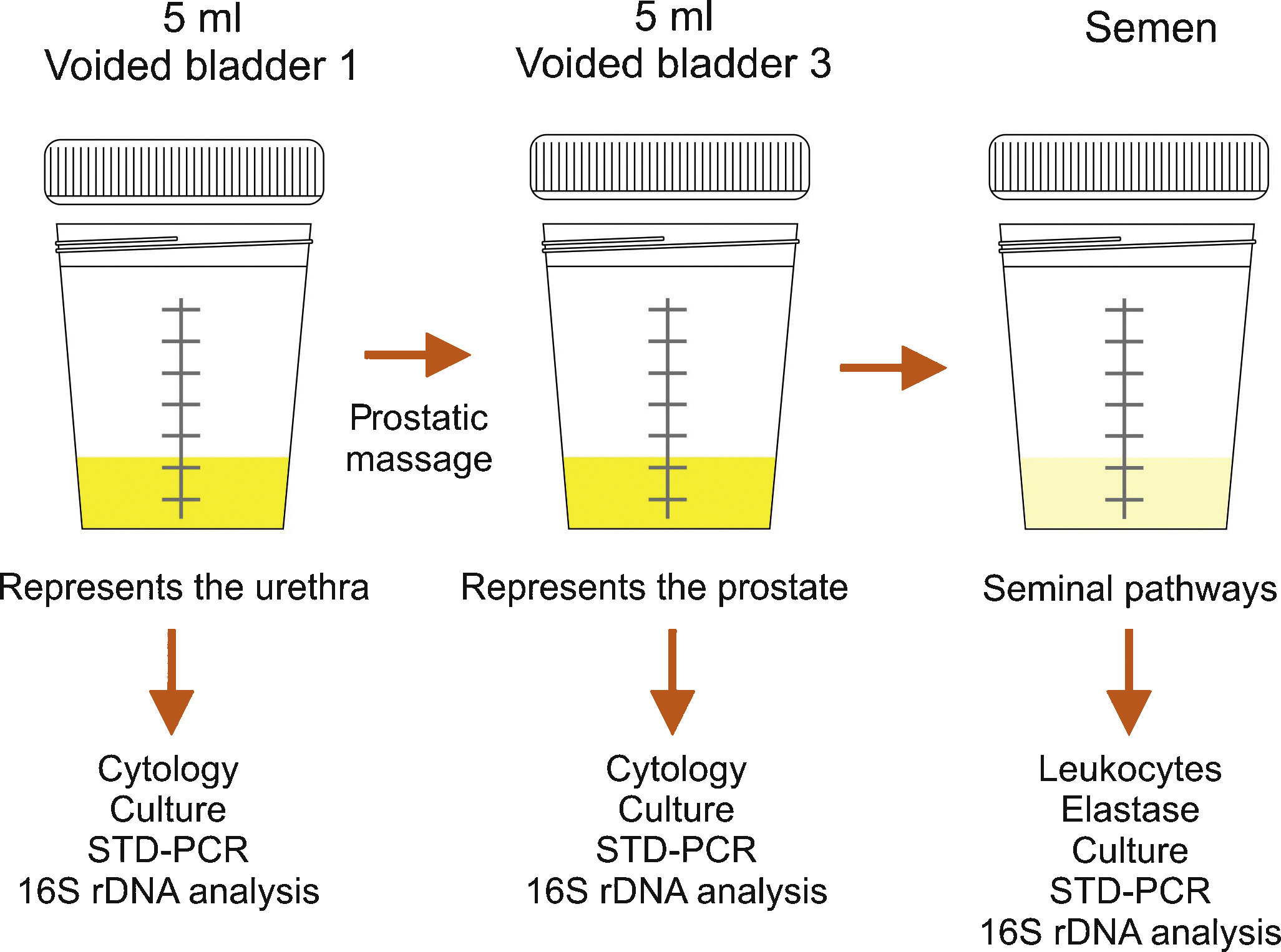

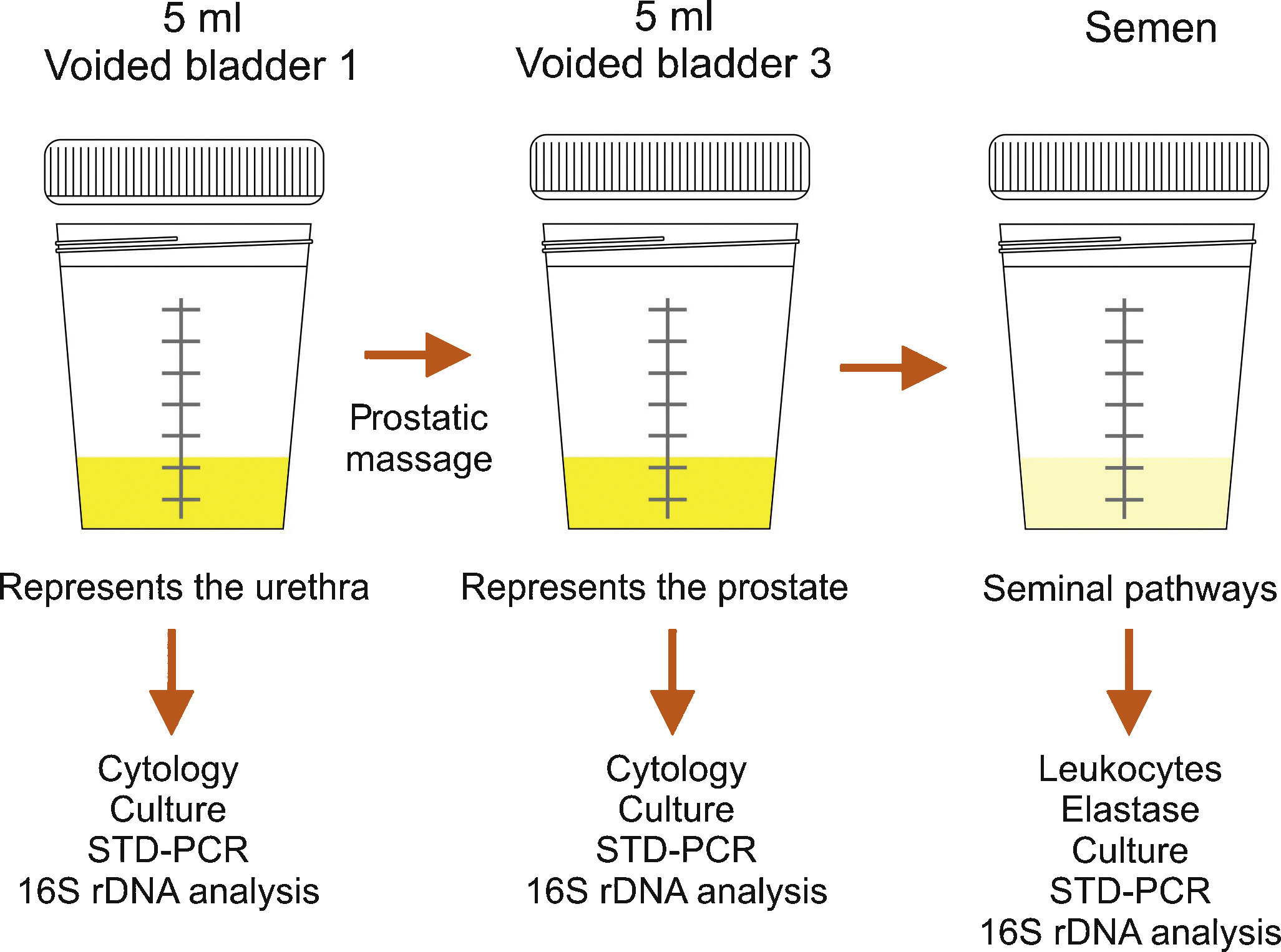

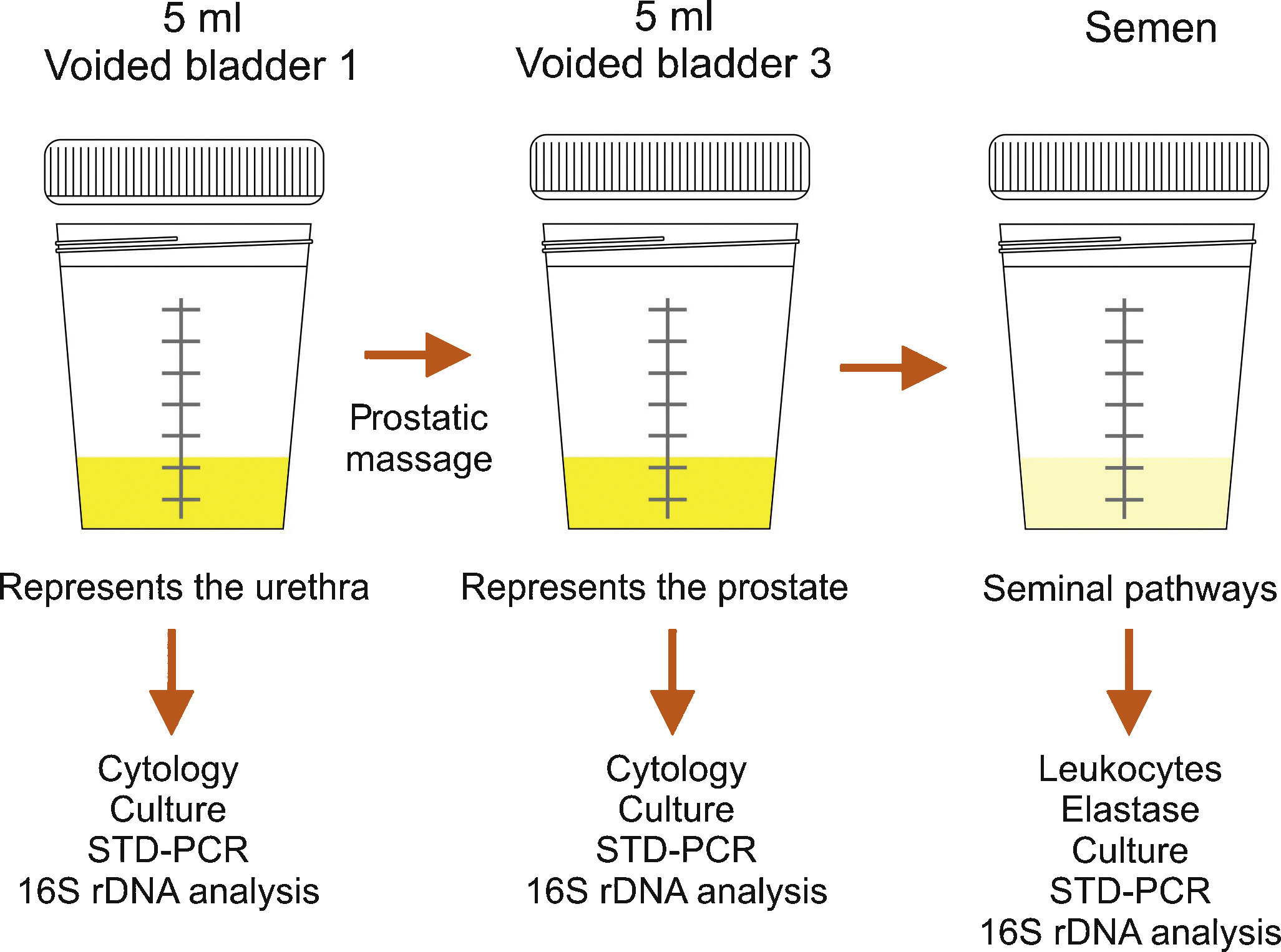

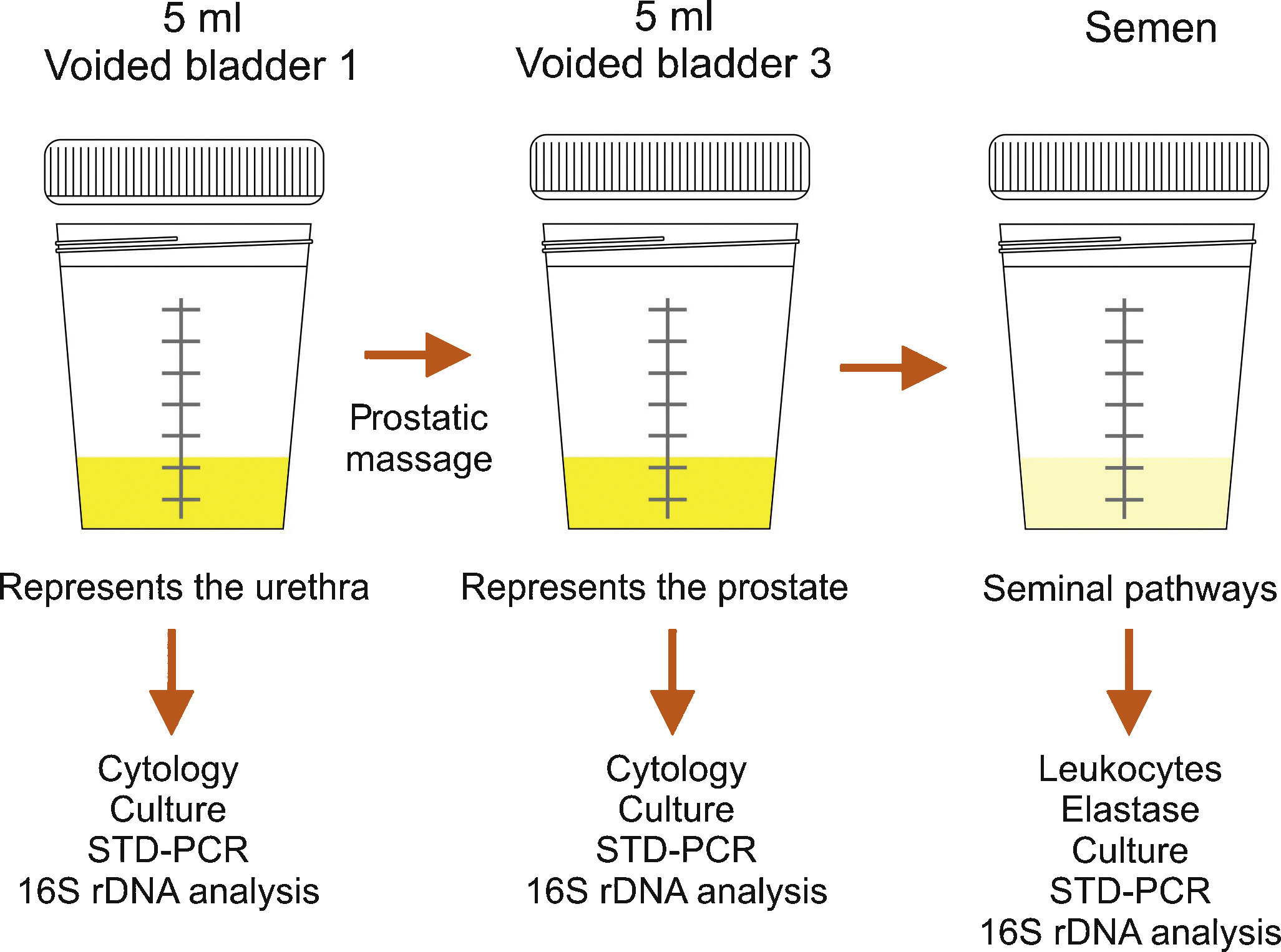

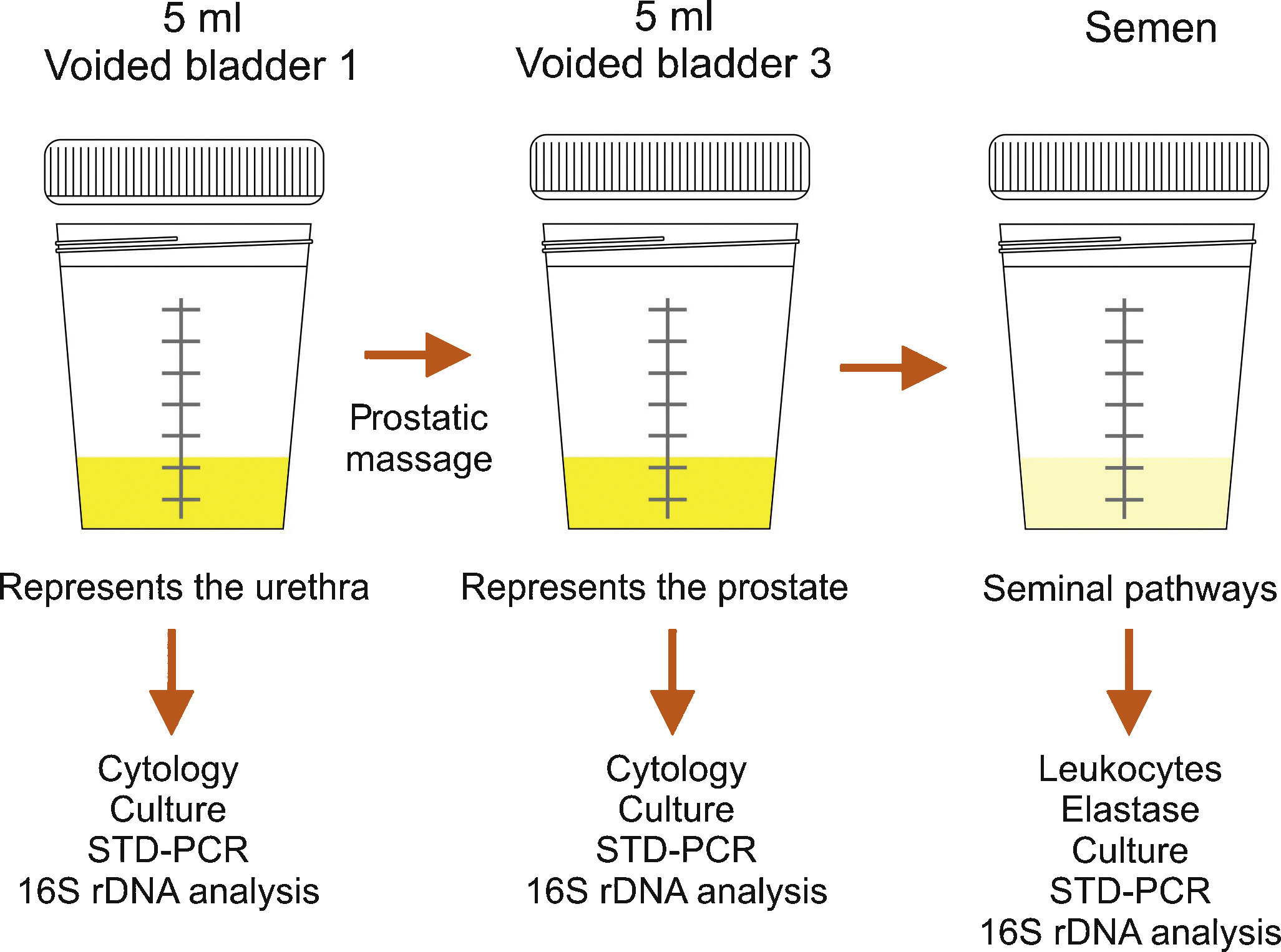

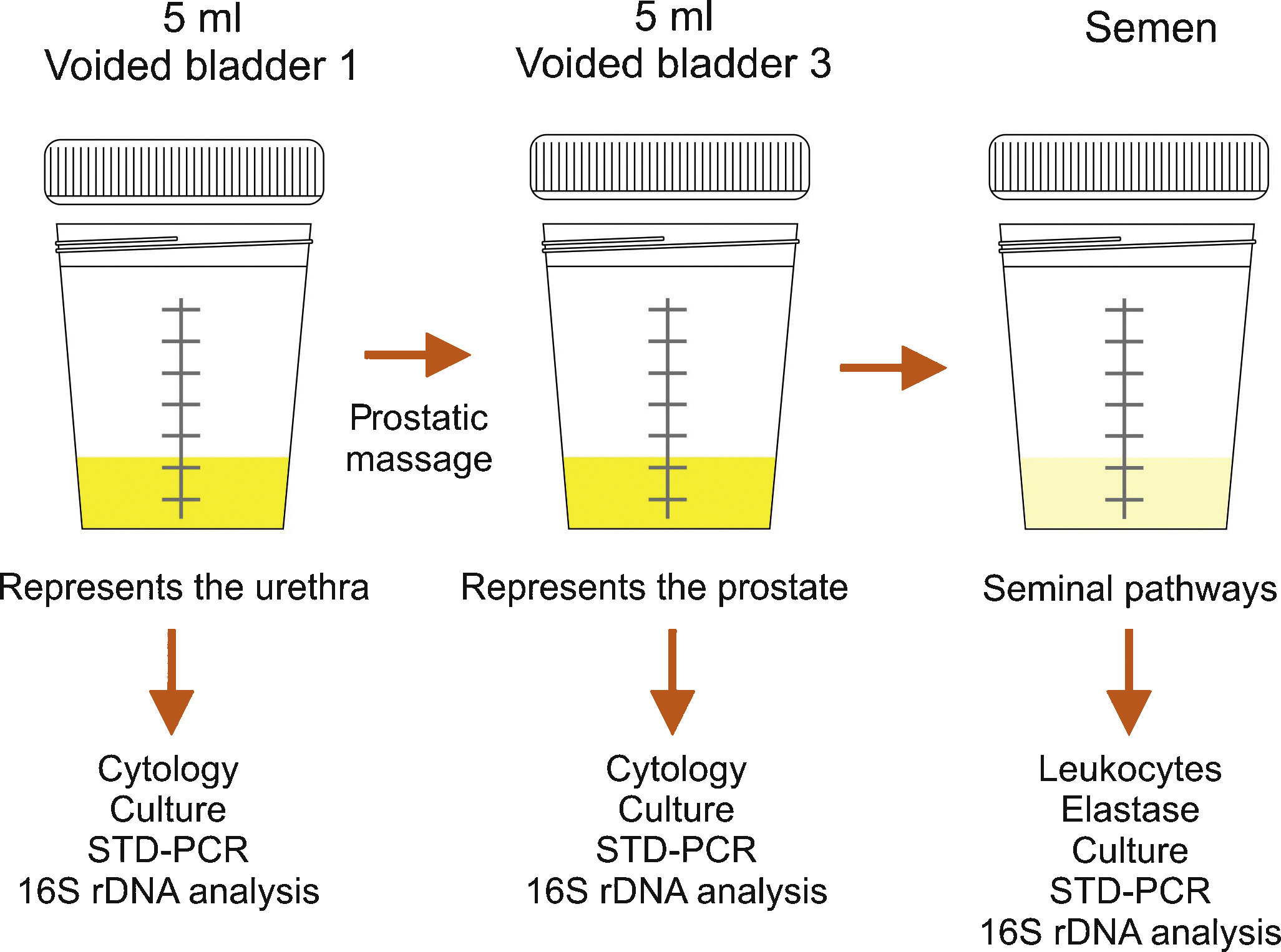

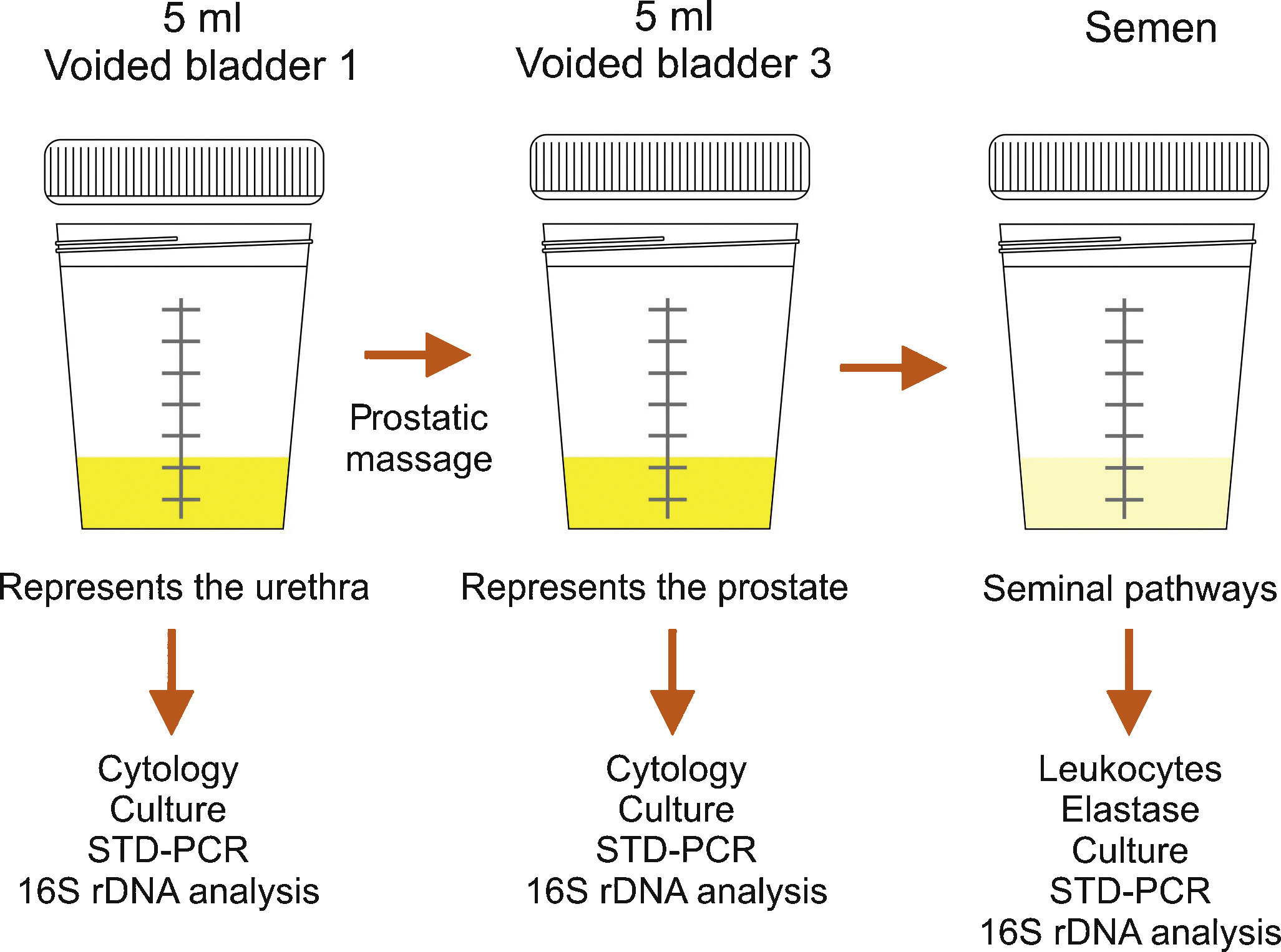

Bacteriological localization cultures are fundamental for the diagnosis of chronic bacterial prostatitis [7] and [11]. In the past, the “4-glass test” was the gold standard [13], but in the meantime, a “2-glass test”, which is a simpler and reasonably accurate alternative [14] and [15], is routinely used in the “Giessen Prostatitis Research Group”. This includes a comparative approach on a cultural basis with a 10-fold increase in voided bladder urine after prostatic massage for diagnosis of CBP (Figure 1). Normally, an ejaculate analysis for bacteriological, cytological or spermatological reasons can be added. The suggestion of the WHO [16] is to do this after passing urine (Figure 1). A good correlation of results with the “2-glass test” has been demonstrated [14] and [15]. Regarding microbiological diagnostics from the “2-glass test” and ejaculate material, a combination of culture-dependent and culture-independent methods has been shown to improve the microbial findings [17]. For bacterial culture, it is of utmost importance to process and cultivate the samples within 2-4 hours after sampling. Storage at 4 °C in the refrigerator decreases the sensitivity of culture-based tests and has to be avoided. The culture-independent tests are not affected by transportation time and consist of two consecutive PCR methods: 1) specific PCR, targeting DNA regions of common STD pathogens such as Mycoplasma genitalium, Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae (STD-PCR), and 2) broad-range PCR, targeting the 16S rRNA gene of bacteria (16S-PCR) and followed by sequencing. 16S-PCR is a highly sensitive method for detecting non-cultivable bacteria and should be applied only if the bacterial culture and the STD-PCR are negative [18]. Further advances in next generation sequencing (NGS) and a fall in the cost of sequencing techniques will soon facilitate comprehensive microbiome analysis of prostate secretions for identifying microbial communities in more detail.

Semen culture of the ejaculate alone is not sufficient for diagnosis of CBP due to a sensibility of only 50% in identifying bacteriospermia [7] and [8]. The most common pathogens are similar to acute bacterial prostatitis (Table 1); fastidious pathogens such as M tuberculosis and Candida sp. need PCR-mediated investigation in the urine [11]. Uncommon microorganisms, e.g. C. trachomatis and Mycoplasma species, may spread to the different accessory glands (see overview in [19]). Until today, proven prostatic infections have not been confirmed for chlamydiae [20]. Obviously, the possibility of urethral infection reduces the biological significance of positive chlamydial finding in post-prostatic massage urine [20]. Questionably increased IL-8 levels and evidence of antichlamydial mucosal IG-A in seminal plasma may be helpful for clarification [21]. The role of Mycoplasma species (M. hominis, M. genitalium, U. urealytium) in prostatitis remains unsettled (see overview in [19]). Recent data suggest a detection rate of 25% in urogenital secretions without an association to urogenital symptoms, depending upon the patient population.

Lower urinary tract symptoms and pelvic pain due to pathologies of the prostate have always affected quality of life in men of all ages. For years, understanding of the condition was based merely on a prostate relationship via an organ pathology involving somatic or visual tissue lesions [5] and [22]. Today, emotional, cognitive, behavioral and sexual responses are also accepted as possible trigger mechanisms for pain symptoms [4], [5], [22], and [23]. The National Institutes of Health Chronic Prostatitis Symptom Index (NIH-CPSI) represents an objective assessment tool and has been validated in many European languages [3], [4], and [22]. As a validated instrument, it is commonly used in clinical trials for measuring treatment response. In this context, the IPPS and the IIEF significantly support initial assessment and the course of disease in response to treatment [7], [8], and [24]. Additionally, the concept of phenotyping of all symptomatic patients in clinical domains is a new issue (see below) for improving therapy [23] (Table 3).

Table 3

Phenotype classification modified according to Shoskes and Nickel [23], [26], and [28]

| U | P | O | I | N | T | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urinary | Psychological | Organ specific | Infection | Neurologic/Systemic | Tenderness | Sexual dysfunction |

| Disturbed voiding | Depression | Inflammatory prostatic secretions | Infection | Instable bowel syndrome, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome | Pelvic floor spasm | Erectile, ejaculatory, orgasmic dysfunction |

The simple “2-glass test” for analyzing the number of leukocytes in VB3 [14] and [15] and an additional ejaculate analysis for counting of leucocytes [7], [8], and [16] can be used to differentiate inflammatory and non-inflammatory CPPS. Various parameters with database cut-off points for inflammatory reaction are used by different groups. There is no validated limit regarding WBCs for differentiating NIH IIIa vs IIIb forms [24]. We suggest complementary parameters in urine after prostate massage, EPS and semen (Table 4) for differentiation purposes [24].

TRUS is normally not indicated [7]. Urodynamics should be proposed to patients with LUTS to rule out bladder neck hypertrophy, bladder outlet obstruction, and vesicosphincter dyssynergia. Uroflowmetry and residual urine bladder scan may produce more sophisticated urodynamics [7]. Cystoscopy is not routinely indicated; in suspected interstitial cystitis, specific diagnostics are mandatory [7] and [11].

An association between male sexual dysfunction and prostatitis syndrome, especially CPPS, has been the subject of controversy for years [25]. Although the exact mechanisms of sexual dysfunction in CPPS have not been elucidated, recent data suggest a multifactorial origin with vascular, endocrine, psychogenic and neuromuscular causes [26]. Consensus data based on a PubMed database analysis confirmed a significant percentage of ED in men suffering from CP/CPPS between 30 to 72 percent, measured using IIEF and NIH-CPSI [27]. Clinical phenotyping of CPPS patients (UPOINT[s]) or adding a sexual dysfunction domain to the standard questionnaire might be helpful [4], [5], and [28]. When discussing etiology of ED in these cases, there are hints that psychogenic factors are mainly relevant in all patients suffering from CPPS and ED [27] and [29]. Another very important entity is the interaction between CPPS symptoms and ejaculatory dysfunction. Based on studies from Asia, premature ejaculation seems to be a significant factor in sexual dysfunction in up to 77% of patients with CPPS (see Overview in 27). It appears similarly important to us that “prostatitis” patients suffer from ejaculatory pain [30] and [31]. The presence of ejaculatory pain in CPPS seems to be associated with more severe symptoms in the NIH-CPSI [31].

Since prostatitis is common in males of reproductive age, a negative impact on semen composition, and thus on fertility, may be suspected. Unfortunately, only a few studies are available investigating different types of prostatitis. In patients with NIH type II prostatitis, a recent meta-analysis evaluated seven studies including 249 patients and 163 controls [32]. While sperm vitality, sperm total motility and the percentage of progressively motile sperm were significantly impaired, no impact was identified regarding semen volume, sperm concentration and semen liquefaction. However, the meta-analysis has to be looked at more carefully, because three studies from China are not available through PubMed. In addition, one study from China published in English looks similar to another study included in the meta-analysis from the same group and has been retracted by the editors of the original journal because of scientific misconduct. Unfortunately, one full study was not included [33]. Thus, further larger studies with adequate control groups are necessary to answer the question of whether chronic bacterial prostatitis has a negative impact on semen parameters. More studies are available investigating NIH type III prostatitis. Again, a recent meta-analysis is available on this population of patients, including a total of 12 studies with 999 patients and 455 controls [34]. The meta-analysis showed that sperm concentration, percentage of progressively motile sperm and sperm morphology of patients were significantly lower than in controls. Limitations include the lack of differentiation between type IIIA and IIIB prostatitis and the heterogeneity of recruited controls, ranging from asymptomatic men to healthy sperm donors with fully normal semen. Finally, prostatitis-like symptoms, defined as a cluster of bothersome perineal and/or ejaculatory pains or general discomfort, were not associated with any sperm parameter investigated in males of infertile couples [35]. In summary, both meta-analyses indicate significant impairment of at least some sperm parameters in patients with prostatitis compared to controls. However, whether the adverse effect on sperm parameters has any impact on fertility has not been proven so far.

Acute bacterial prostatitis is a serious infection. The main symptoms are high fever, pelvic pain and general discomfort. It can also result in septicemia and urosepsis, with elevated risk for the patient's life and mandatory hospitalization [36]. Initial antibiotic treatment is empirical and experience-based [37]. A broad-spectrum penicillin derivative with a beta-lactamase inhibitor, third-generation cephalosporin or fluoroquinolone, possibly in association with aminoglycoside, is suggested [10] and [11]. Patients without complicated symptoms may be treated with oral fluoroquinolones [37], [38], and [39]. After initial improvement and evaluation of bacterial susceptibility, appropriate oral therapy can be administered and should be performed for at least 4 weeks [24]. Some authors suggest suprapubic catheterization in the event of urinary retention to avoid a blockade of the prostate ducts by a transurethral catheter [9] and [24]. If a prostatic abscess is identified which is more than 1 cm in diameter, it should be aspirated and drained [7] and [9].

Due to their proven pharmacokinetic properties and antimicrobial spectrum, fluoroquinolones (especially levofloxacin and ciprofloxacin) are the most recommended antibiotics agents for treating chronic bacterial prostatitis [11], [37], [38], and [39]. They have a strong antimicrobial effect on the most common Gram-negative, Gram-positive and atypical pathogens. The recommended administration period is about 4 weeks [10] and [11]. Some evidence also points to the efficacy of macrolides [40]. In the event of resistance to fluoroquinolones, a 3-month therapy with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole has been suggested [10]. Table 5 summarizes therapeutic suggestions of the Giessen group. No advantage of a combination of antimicrobials and alpha-blockers [41] has been proven.

Due to the complexity of the pathogenetic mechanisms and the heterogeneity of symptoms, understanding CPPS, especially the appropriate therapeutic approach, is still a challenge and a matter of debate [5]. Up to now, the efficacy of a monotherapy has not really been proven despite a meta-analysis of many common treatments such as alpha-blockers, antibiotics, alpha-blockers and antibiotics, anti-inflammatory working substances and phytotherapy [42].

Due to this unsatisfactory situation, a multimodal therapy seems to be the best approach [43] if the above mentioned UPOINT(s) system involving all clinical domains (Table 3) is used. Symptom severity is assessed using NIH-CPSI and the patient should show a positive development, whereby a minimum 6-point drop in the total scale is considered a successful endpoint. A web-based algorithm is also available at http://www.upointmd.com. Other therapeutic approaches include psychological support in patients with enduring symptoms and depression [44] and [45], while surgical procedures in cases where an anatomical cause of obstruction is proven [6] and [11] are an ongoing matter of debate [7]. Physiotherapeutic “pelvic floor” relaxant options have been suggested, including shock-wave therapy of the prostatic area [45] and [46]. There is no evidence that therapy of prostatitis-syndrome improves sexual function. One myth is that the frequency of sexual activity may change prostatic health and sexual activity [47]. Both refraining from ejaculation and an increase in regular sexual activity with high ejaculatory frequency have been suggested as factors for improving sexual function (see Overview in 27). Also the benefit of PDE-5 inhibitors has been discussed although data analysis does not provide clear evidence of efficacy on sexual dysfunction in CPPS patients outside cohorts with predominant LUTS [48].

It is nowadays generally agreed that this condition does not require additional diagnosis or therapy. Antimicrobial therapy can be suggested to patients with raised PSA [24], but evidence-based data are lacking.

Dr. Benelli is assigned to Giessen University for “Uro-Andrology” for one year

Supported by Excellence Initiative of Hessen: LOEWE: Urogenital infection/inflammation and male infertility (MIBIE)

Diagnosis of prostatitis refers to a variety of inflammatory and non-inflammatory, symptomatic and non-symptomatic entities often not affecting the prostate gland. Prostatitis syndrome has been classified in a consensus process as infectious disease (acute and chronic), chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CPPS) and asymptomatic prostatitis [1] (Table 1). Prostatitis-like symptoms, especially pelvic pain, occur with a prevalence of about 8% [2], with severe symptoms especially in CPPS. The National Institutes of Health Chronic Prostatitis Syndrome Index (NIH-CPSI) represents world-wide the validated assessment tool for evaluating prostatitis-like symptoms [3] and [4]. Only Category IV prostatitis is asymptomatic with the diagnosis normally resulting from histological evaluation by biopsy [4].

Table 1

NIH classification system for prostatitis syndromes [1]

| Category | Nomenclature |

|---|---|

| I | Acute bacterial prostatitis |

| II | Chronic bacterial prostatitis |

| III | Chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CPPS) |

| III A | Inflammatory |

| III B | Non-inflammatory |

| IV | Asymptomatic prostatitis |

In clinical practice, 90 percent of outpatients suffer from CPPS, inflammatory or non-inflammatory disease [5] and [6]. Management of pelvic pain is a major challenge for the urologist [5]. Men with proven bacterial prostatitis need meticulous diagnostic management and therapy, some of them have to be hospitalized [6], [7], [8], [9], and [10].

This review covers accepted aspects of diagnostic procedures and therapeutic attempts in men suffering from symptomatic prostatitis and CPPS (Categories I to III).

Careful medical history (e.g. physical examination) investigating presence of fever and voiding dysfunction is fundamental. It should include scrotal evaluation and a gentle digital rectal examination without prostate massage, which is not recommended due to the risk of bacterial dissemination. The prostate is usually described as tender and swollen [6], [7], [8], and [9].

Diagnosis is based on microscopic analysis of a midstream urine specimen with evidence of leucocytes and confirmed by a microbiological culture, which is mandatory and the only laboratory examination required [7], [10], and [11]. Enterobacteriaceae, especially E. coli, are most common (Table 2) [6], [7], and [11]. Prostatic specific antigen is often increased and may be used diagnostically [7] and [9].

Table 2

Common pathogens in bacterial prostatitis (NIH I, II) [6] and [11]

| Etiologically recognized pathogens | Microorganisms of debatable significance | Fastidious microorganisms |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | Staphylococci | M. tuberculosis |

| Klebsiella sp. | Streptococci | Candida sp. |

| Proteus mirabilis | Corynebacterium sp. |

|

| Enterococcus faecalis | C. trachomatis |

|

| P. aeruginosa | U. urealyticum |

|

|

|

M. hominis |

|

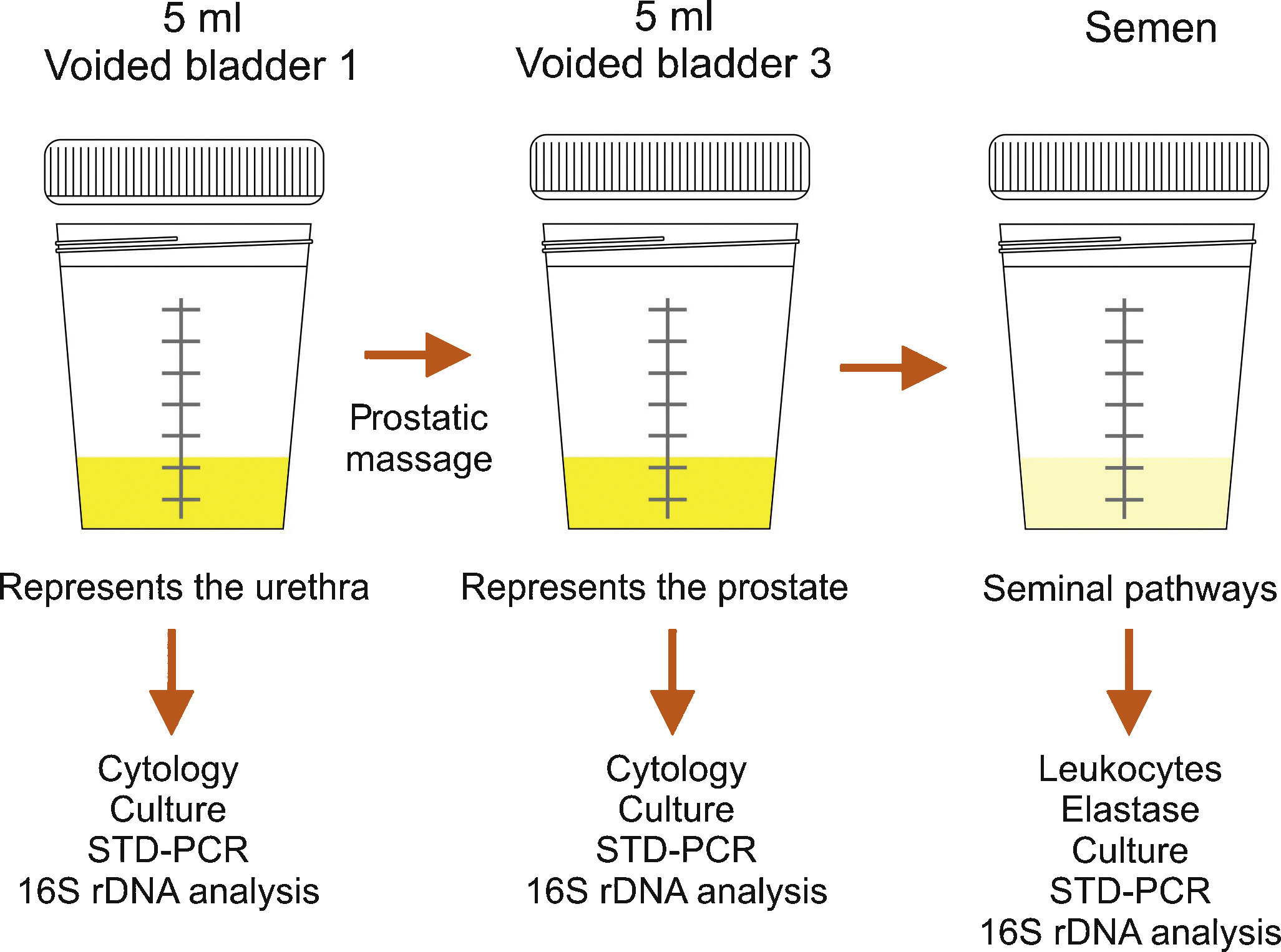

Bacteriological localization cultures are fundamental for the diagnosis of chronic bacterial prostatitis [7] and [11]. In the past, the “4-glass test” was the gold standard [13], but in the meantime, a “2-glass test”, which is a simpler and reasonably accurate alternative [14] and [15], is routinely used in the “Giessen Prostatitis Research Group”. This includes a comparative approach on a cultural basis with a 10-fold increase in voided bladder urine after prostatic massage for diagnosis of CBP (Figure 1). Normally, an ejaculate analysis for bacteriological, cytological or spermatological reasons can be added. The suggestion of the WHO [16] is to do this after passing urine (Figure 1). A good correlation of results with the “2-glass test” has been demonstrated [14] and [15]. Regarding microbiological diagnostics from the “2-glass test” and ejaculate material, a combination of culture-dependent and culture-independent methods has been shown to improve the microbial findings [17]. For bacterial culture, it is of utmost importance to process and cultivate the samples within 2-4 hours after sampling. Storage at 4 °C in the refrigerator decreases the sensitivity of culture-based tests and has to be avoided. The culture-independent tests are not affected by transportation time and consist of two consecutive PCR methods: 1) specific PCR, targeting DNA regions of common STD pathogens such as Mycoplasma genitalium, Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae (STD-PCR), and 2) broad-range PCR, targeting the 16S rRNA gene of bacteria (16S-PCR) and followed by sequencing. 16S-PCR is a highly sensitive method for detecting non-cultivable bacteria and should be applied only if the bacterial culture and the STD-PCR are negative [18]. Further advances in next generation sequencing (NGS) and a fall in the cost of sequencing techniques will soon facilitate comprehensive microbiome analysis of prostate secretions for identifying microbial communities in more detail.

Semen culture of the ejaculate alone is not sufficient for diagnosis of CBP due to a sensibility of only 50% in identifying bacteriospermia [7] and [8]. The most common pathogens are similar to acute bacterial prostatitis (Table 1); fastidious pathogens such as M tuberculosis and Candida sp. need PCR-mediated investigation in the urine [11]. Uncommon microorganisms, e.g. C. trachomatis and Mycoplasma species, may spread to the different accessory glands (see overview in [19]). Until today, proven prostatic infections have not been confirmed for chlamydiae [20]. Obviously, the possibility of urethral infection reduces the biological significance of positive chlamydial finding in post-prostatic massage urine [20]. Questionably increased IL-8 levels and evidence of antichlamydial mucosal IG-A in seminal plasma may be helpful for clarification [21]. The role of Mycoplasma species (M. hominis, M. genitalium, U. urealytium) in prostatitis remains unsettled (see overview in [19]). Recent data suggest a detection rate of 25% in urogenital secretions without an association to urogenital symptoms, depending upon the patient population.

Lower urinary tract symptoms and pelvic pain due to pathologies of the prostate have always affected quality of life in men of all ages. For years, understanding of the condition was based merely on a prostate relationship via an organ pathology involving somatic or visual tissue lesions [5] and [22]. Today, emotional, cognitive, behavioral and sexual responses are also accepted as possible trigger mechanisms for pain symptoms [4], [5], [22], and [23]. The National Institutes of Health Chronic Prostatitis Symptom Index (NIH-CPSI) represents an objective assessment tool and has been validated in many European languages [3], [4], and [22]. As a validated instrument, it is commonly used in clinical trials for measuring treatment response. In this context, the IPPS and the IIEF significantly support initial assessment and the course of disease in response to treatment [7], [8], and [24]. Additionally, the concept of phenotyping of all symptomatic patients in clinical domains is a new issue (see below) for improving therapy [23] (Table 3).

Table 3

Phenotype classification modified according to Shoskes and Nickel [23], [26], and [28]

| U | P | O | I | N | T | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urinary | Psychological | Organ specific | Infection | Neurologic/Systemic | Tenderness | Sexual dysfunction |

| Disturbed voiding | Depression | Inflammatory prostatic secretions | Infection | Instable bowel syndrome, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome | Pelvic floor spasm | Erectile, ejaculatory, orgasmic dysfunction |

The simple “2-glass test” for analyzing the number of leukocytes in VB3 [14] and [15] and an additional ejaculate analysis for counting of leucocytes [7], [8], and [16] can be used to differentiate inflammatory and non-inflammatory CPPS. Various parameters with database cut-off points for inflammatory reaction are used by different groups. There is no validated limit regarding WBCs for differentiating NIH IIIa vs IIIb forms [24]. We suggest complementary parameters in urine after prostate massage, EPS and semen (Table 4) for differentiation purposes [24].

TRUS is normally not indicated [7]. Urodynamics should be proposed to patients with LUTS to rule out bladder neck hypertrophy, bladder outlet obstruction, and vesicosphincter dyssynergia. Uroflowmetry and residual urine bladder scan may produce more sophisticated urodynamics [7]. Cystoscopy is not routinely indicated; in suspected interstitial cystitis, specific diagnostics are mandatory [7] and [11].

An association between male sexual dysfunction and prostatitis syndrome, especially CPPS, has been the subject of controversy for years [25]. Although the exact mechanisms of sexual dysfunction in CPPS have not been elucidated, recent data suggest a multifactorial origin with vascular, endocrine, psychogenic and neuromuscular causes [26]. Consensus data based on a PubMed database analysis confirmed a significant percentage of ED in men suffering from CP/CPPS between 30 to 72 percent, measured using IIEF and NIH-CPSI [27]. Clinical phenotyping of CPPS patients (UPOINT[s]) or adding a sexual dysfunction domain to the standard questionnaire might be helpful [4], [5], and [28]. When discussing etiology of ED in these cases, there are hints that psychogenic factors are mainly relevant in all patients suffering from CPPS and ED [27] and [29]. Another very important entity is the interaction between CPPS symptoms and ejaculatory dysfunction. Based on studies from Asia, premature ejaculation seems to be a significant factor in sexual dysfunction in up to 77% of patients with CPPS (see Overview in 27). It appears similarly important to us that “prostatitis” patients suffer from ejaculatory pain [30] and [31]. The presence of ejaculatory pain in CPPS seems to be associated with more severe symptoms in the NIH-CPSI [31].

Since prostatitis is common in males of reproductive age, a negative impact on semen composition, and thus on fertility, may be suspected. Unfortunately, only a few studies are available investigating different types of prostatitis. In patients with NIH type II prostatitis, a recent meta-analysis evaluated seven studies including 249 patients and 163 controls [32]. While sperm vitality, sperm total motility and the percentage of progressively motile sperm were significantly impaired, no impact was identified regarding semen volume, sperm concentration and semen liquefaction. However, the meta-analysis has to be looked at more carefully, because three studies from China are not available through PubMed. In addition, one study from China published in English looks similar to another study included in the meta-analysis from the same group and has been retracted by the editors of the original journal because of scientific misconduct. Unfortunately, one full study was not included [33]. Thus, further larger studies with adequate control groups are necessary to answer the question of whether chronic bacterial prostatitis has a negative impact on semen parameters. More studies are available investigating NIH type III prostatitis. Again, a recent meta-analysis is available on this population of patients, including a total of 12 studies with 999 patients and 455 controls [34]. The meta-analysis showed that sperm concentration, percentage of progressively motile sperm and sperm morphology of patients were significantly lower than in controls. Limitations include the lack of differentiation between type IIIA and IIIB prostatitis and the heterogeneity of recruited controls, ranging from asymptomatic men to healthy sperm donors with fully normal semen. Finally, prostatitis-like symptoms, defined as a cluster of bothersome perineal and/or ejaculatory pains or general discomfort, were not associated with any sperm parameter investigated in males of infertile couples [35]. In summary, both meta-analyses indicate significant impairment of at least some sperm parameters in patients with prostatitis compared to controls. However, whether the adverse effect on sperm parameters has any impact on fertility has not been proven so far.

Acute bacterial prostatitis is a serious infection. The main symptoms are high fever, pelvic pain and general discomfort. It can also result in septicemia and urosepsis, with elevated risk for the patient's life and mandatory hospitalization [36]. Initial antibiotic treatment is empirical and experience-based [37]. A broad-spectrum penicillin derivative with a beta-lactamase inhibitor, third-generation cephalosporin or fluoroquinolone, possibly in association with aminoglycoside, is suggested [10] and [11]. Patients without complicated symptoms may be treated with oral fluoroquinolones [37], [38], and [39]. After initial improvement and evaluation of bacterial susceptibility, appropriate oral therapy can be administered and should be performed for at least 4 weeks [24]. Some authors suggest suprapubic catheterization in the event of urinary retention to avoid a blockade of the prostate ducts by a transurethral catheter [9] and [24]. If a prostatic abscess is identified which is more than 1 cm in diameter, it should be aspirated and drained [7] and [9].

Due to their proven pharmacokinetic properties and antimicrobial spectrum, fluoroquinolones (especially levofloxacin and ciprofloxacin) are the most recommended antibiotics agents for treating chronic bacterial prostatitis [11], [37], [38], and [39]. They have a strong antimicrobial effect on the most common Gram-negative, Gram-positive and atypical pathogens. The recommended administration period is about 4 weeks [10] and [11]. Some evidence also points to the efficacy of macrolides [40]. In the event of resistance to fluoroquinolones, a 3-month therapy with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole has been suggested [10]. Table 5 summarizes therapeutic suggestions of the Giessen group. No advantage of a combination of antimicrobials and alpha-blockers [41] has been proven.

Due to the complexity of the pathogenetic mechanisms and the heterogeneity of symptoms, understanding CPPS, especially the appropriate therapeutic approach, is still a challenge and a matter of debate [5]. Up to now, the efficacy of a monotherapy has not really been proven despite a meta-analysis of many common treatments such as alpha-blockers, antibiotics, alpha-blockers and antibiotics, anti-inflammatory working substances and phytotherapy [42].

Due to this unsatisfactory situation, a multimodal therapy seems to be the best approach [43] if the above mentioned UPOINT(s) system involving all clinical domains (Table 3) is used. Symptom severity is assessed using NIH-CPSI and the patient should show a positive development, whereby a minimum 6-point drop in the total scale is considered a successful endpoint. A web-based algorithm is also available at http://www.upointmd.com. Other therapeutic approaches include psychological support in patients with enduring symptoms and depression [44] and [45], while surgical procedures in cases where an anatomical cause of obstruction is proven [6] and [11] are an ongoing matter of debate [7]. Physiotherapeutic “pelvic floor” relaxant options have been suggested, including shock-wave therapy of the prostatic area [45] and [46]. There is no evidence that therapy of prostatitis-syndrome improves sexual function. One myth is that the frequency of sexual activity may change prostatic health and sexual activity [47]. Both refraining from ejaculation and an increase in regular sexual activity with high ejaculatory frequency have been suggested as factors for improving sexual function (see Overview in 27). Also the benefit of PDE-5 inhibitors has been discussed although data analysis does not provide clear evidence of efficacy on sexual dysfunction in CPPS patients outside cohorts with predominant LUTS [48].

It is nowadays generally agreed that this condition does not require additional diagnosis or therapy. Antimicrobial therapy can be suggested to patients with raised PSA [24], but evidence-based data are lacking.

Dr. Benelli is assigned to Giessen University for “Uro-Andrology” for one year

Supported by Excellence Initiative of Hessen: LOEWE: Urogenital infection/inflammation and male infertility (MIBIE)

Diagnosis of prostatitis refers to a variety of inflammatory and non-inflammatory, symptomatic and non-symptomatic entities often not affecting the prostate gland. Prostatitis syndrome has been classified in a consensus process as infectious disease (acute and chronic), chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CPPS) and asymptomatic prostatitis [1] (Table 1). Prostatitis-like symptoms, especially pelvic pain, occur with a prevalence of about 8% [2], with severe symptoms especially in CPPS. The National Institutes of Health Chronic Prostatitis Syndrome Index (NIH-CPSI) represents world-wide the validated assessment tool for evaluating prostatitis-like symptoms [3] and [4]. Only Category IV prostatitis is asymptomatic with the diagnosis normally resulting from histological evaluation by biopsy [4].

Table 1

NIH classification system for prostatitis syndromes [1]

| Category | Nomenclature |

|---|---|

| I | Acute bacterial prostatitis |

| II | Chronic bacterial prostatitis |

| III | Chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CPPS) |

| III A | Inflammatory |

| III B | Non-inflammatory |

| IV | Asymptomatic prostatitis |

In clinical practice, 90 percent of outpatients suffer from CPPS, inflammatory or non-inflammatory disease [5] and [6]. Management of pelvic pain is a major challenge for the urologist [5]. Men with proven bacterial prostatitis need meticulous diagnostic management and therapy, some of them have to be hospitalized [6], [7], [8], [9], and [10].

This review covers accepted aspects of diagnostic procedures and therapeutic attempts in men suffering from symptomatic prostatitis and CPPS (Categories I to III).

Careful medical history (e.g. physical examination) investigating presence of fever and voiding dysfunction is fundamental. It should include scrotal evaluation and a gentle digital rectal examination without prostate massage, which is not recommended due to the risk of bacterial dissemination. The prostate is usually described as tender and swollen [6], [7], [8], and [9].

Diagnosis is based on microscopic analysis of a midstream urine specimen with evidence of leucocytes and confirmed by a microbiological culture, which is mandatory and the only laboratory examination required [7], [10], and [11]. Enterobacteriaceae, especially E. coli, are most common (Table 2) [6], [7], and [11]. Prostatic specific antigen is often increased and may be used diagnostically [7] and [9].

Table 2

Common pathogens in bacterial prostatitis (NIH I, II) [6] and [11]

| Etiologically recognized pathogens | Microorganisms of debatable significance | Fastidious microorganisms |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | Staphylococci | M. tuberculosis |

| Klebsiella sp. | Streptococci | Candida sp. |

| Proteus mirabilis | Corynebacterium sp. |

|

| Enterococcus faecalis | C. trachomatis |

|

| P. aeruginosa | U. urealyticum |

|

|

|

M. hominis |

|

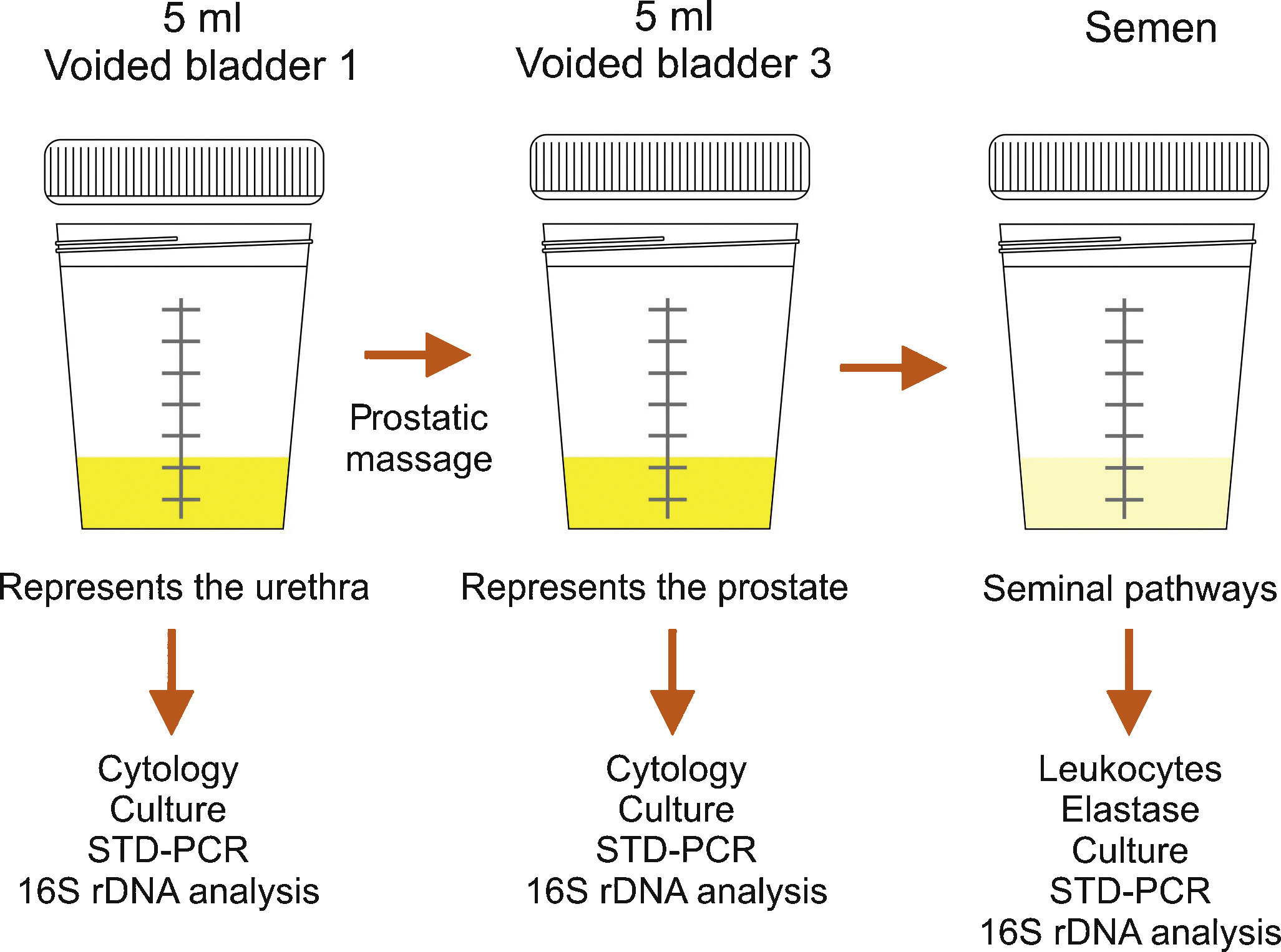

Bacteriological localization cultures are fundamental for the diagnosis of chronic bacterial prostatitis [7] and [11]. In the past, the “4-glass test” was the gold standard [13], but in the meantime, a “2-glass test”, which is a simpler and reasonably accurate alternative [14] and [15], is routinely used in the “Giessen Prostatitis Research Group”. This includes a comparative approach on a cultural basis with a 10-fold increase in voided bladder urine after prostatic massage for diagnosis of CBP (Figure 1). Normally, an ejaculate analysis for bacteriological, cytological or spermatological reasons can be added. The suggestion of the WHO [16] is to do this after passing urine (Figure 1). A good correlation of results with the “2-glass test” has been demonstrated [14] and [15]. Regarding microbiological diagnostics from the “2-glass test” and ejaculate material, a combination of culture-dependent and culture-independent methods has been shown to improve the microbial findings [17]. For bacterial culture, it is of utmost importance to process and cultivate the samples within 2-4 hours after sampling. Storage at 4 °C in the refrigerator decreases the sensitivity of culture-based tests and has to be avoided. The culture-independent tests are not affected by transportation time and consist of two consecutive PCR methods: 1) specific PCR, targeting DNA regions of common STD pathogens such as Mycoplasma genitalium, Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae (STD-PCR), and 2) broad-range PCR, targeting the 16S rRNA gene of bacteria (16S-PCR) and followed by sequencing. 16S-PCR is a highly sensitive method for detecting non-cultivable bacteria and should be applied only if the bacterial culture and the STD-PCR are negative [18]. Further advances in next generation sequencing (NGS) and a fall in the cost of sequencing techniques will soon facilitate comprehensive microbiome analysis of prostate secretions for identifying microbial communities in more detail.

Semen culture of the ejaculate alone is not sufficient for diagnosis of CBP due to a sensibility of only 50% in identifying bacteriospermia [7] and [8]. The most common pathogens are similar to acute bacterial prostatitis (Table 1); fastidious pathogens such as M tuberculosis and Candida sp. need PCR-mediated investigation in the urine [11]. Uncommon microorganisms, e.g. C. trachomatis and Mycoplasma species, may spread to the different accessory glands (see overview in [19]). Until today, proven prostatic infections have not been confirmed for chlamydiae [20]. Obviously, the possibility of urethral infection reduces the biological significance of positive chlamydial finding in post-prostatic massage urine [20]. Questionably increased IL-8 levels and evidence of antichlamydial mucosal IG-A in seminal plasma may be helpful for clarification [21]. The role of Mycoplasma species (M. hominis, M. genitalium, U. urealytium) in prostatitis remains unsettled (see overview in [19]). Recent data suggest a detection rate of 25% in urogenital secretions without an association to urogenital symptoms, depending upon the patient population.

Lower urinary tract symptoms and pelvic pain due to pathologies of the prostate have always affected quality of life in men of all ages. For years, understanding of the condition was based merely on a prostate relationship via an organ pathology involving somatic or visual tissue lesions [5] and [22]. Today, emotional, cognitive, behavioral and sexual responses are also accepted as possible trigger mechanisms for pain symptoms [4], [5], [22], and [23]. The National Institutes of Health Chronic Prostatitis Symptom Index (NIH-CPSI) represents an objective assessment tool and has been validated in many European languages [3], [4], and [22]. As a validated instrument, it is commonly used in clinical trials for measuring treatment response. In this context, the IPPS and the IIEF significantly support initial assessment and the course of disease in response to treatment [7], [8], and [24]. Additionally, the concept of phenotyping of all symptomatic patients in clinical domains is a new issue (see below) for improving therapy [23] (Table 3).

Table 3

Phenotype classification modified according to Shoskes and Nickel [23], [26], and [28]

| U | P | O | I | N | T | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urinary | Psychological | Organ specific | Infection | Neurologic/Systemic | Tenderness | Sexual dysfunction |

| Disturbed voiding | Depression | Inflammatory prostatic secretions | Infection | Instable bowel syndrome, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome | Pelvic floor spasm | Erectile, ejaculatory, orgasmic dysfunction |

The simple “2-glass test” for analyzing the number of leukocytes in VB3 [14] and [15] and an additional ejaculate analysis for counting of leucocytes [7], [8], and [16] can be used to differentiate inflammatory and non-inflammatory CPPS. Various parameters with database cut-off points for inflammatory reaction are used by different groups. There is no validated limit regarding WBCs for differentiating NIH IIIa vs IIIb forms [24]. We suggest complementary parameters in urine after prostate massage, EPS and semen (Table 4) for differentiation purposes [24].

TRUS is normally not indicated [7]. Urodynamics should be proposed to patients with LUTS to rule out bladder neck hypertrophy, bladder outlet obstruction, and vesicosphincter dyssynergia. Uroflowmetry and residual urine bladder scan may produce more sophisticated urodynamics [7]. Cystoscopy is not routinely indicated; in suspected interstitial cystitis, specific diagnostics are mandatory [7] and [11].

An association between male sexual dysfunction and prostatitis syndrome, especially CPPS, has been the subject of controversy for years [25]. Although the exact mechanisms of sexual dysfunction in CPPS have not been elucidated, recent data suggest a multifactorial origin with vascular, endocrine, psychogenic and neuromuscular causes [26]. Consensus data based on a PubMed database analysis confirmed a significant percentage of ED in men suffering from CP/CPPS between 30 to 72 percent, measured using IIEF and NIH-CPSI [27]. Clinical phenotyping of CPPS patients (UPOINT[s]) or adding a sexual dysfunction domain to the standard questionnaire might be helpful [4], [5], and [28]. When discussing etiology of ED in these cases, there are hints that psychogenic factors are mainly relevant in all patients suffering from CPPS and ED [27] and [29]. Another very important entity is the interaction between CPPS symptoms and ejaculatory dysfunction. Based on studies from Asia, premature ejaculation seems to be a significant factor in sexual dysfunction in up to 77% of patients with CPPS (see Overview in 27). It appears similarly important to us that “prostatitis” patients suffer from ejaculatory pain [30] and [31]. The presence of ejaculatory pain in CPPS seems to be associated with more severe symptoms in the NIH-CPSI [31].

Since prostatitis is common in males of reproductive age, a negative impact on semen composition, and thus on fertility, may be suspected. Unfortunately, only a few studies are available investigating different types of prostatitis. In patients with NIH type II prostatitis, a recent meta-analysis evaluated seven studies including 249 patients and 163 controls [32]. While sperm vitality, sperm total motility and the percentage of progressively motile sperm were significantly impaired, no impact was identified regarding semen volume, sperm concentration and semen liquefaction. However, the meta-analysis has to be looked at more carefully, because three studies from China are not available through PubMed. In addition, one study from China published in English looks similar to another study included in the meta-analysis from the same group and has been retracted by the editors of the original journal because of scientific misconduct. Unfortunately, one full study was not included [33]. Thus, further larger studies with adequate control groups are necessary to answer the question of whether chronic bacterial prostatitis has a negative impact on semen parameters. More studies are available investigating NIH type III prostatitis. Again, a recent meta-analysis is available on this population of patients, including a total of 12 studies with 999 patients and 455 controls [34]. The meta-analysis showed that sperm concentration, percentage of progressively motile sperm and sperm morphology of patients were significantly lower than in controls. Limitations include the lack of differentiation between type IIIA and IIIB prostatitis and the heterogeneity of recruited controls, ranging from asymptomatic men to healthy sperm donors with fully normal semen. Finally, prostatitis-like symptoms, defined as a cluster of bothersome perineal and/or ejaculatory pains or general discomfort, were not associated with any sperm parameter investigated in males of infertile couples [35]. In summary, both meta-analyses indicate significant impairment of at least some sperm parameters in patients with prostatitis compared to controls. However, whether the adverse effect on sperm parameters has any impact on fertility has not been proven so far.

Acute bacterial prostatitis is a serious infection. The main symptoms are high fever, pelvic pain and general discomfort. It can also result in septicemia and urosepsis, with elevated risk for the patient's life and mandatory hospitalization [36]. Initial antibiotic treatment is empirical and experience-based [37]. A broad-spectrum penicillin derivative with a beta-lactamase inhibitor, third-generation cephalosporin or fluoroquinolone, possibly in association with aminoglycoside, is suggested [10] and [11]. Patients without complicated symptoms may be treated with oral fluoroquinolones [37], [38], and [39]. After initial improvement and evaluation of bacterial susceptibility, appropriate oral therapy can be administered and should be performed for at least 4 weeks [24]. Some authors suggest suprapubic catheterization in the event of urinary retention to avoid a blockade of the prostate ducts by a transurethral catheter [9] and [24]. If a prostatic abscess is identified which is more than 1 cm in diameter, it should be aspirated and drained [7] and [9].

Due to their proven pharmacokinetic properties and antimicrobial spectrum, fluoroquinolones (especially levofloxacin and ciprofloxacin) are the most recommended antibiotics agents for treating chronic bacterial prostatitis [11], [37], [38], and [39]. They have a strong antimicrobial effect on the most common Gram-negative, Gram-positive and atypical pathogens. The recommended administration period is about 4 weeks [10] and [11]. Some evidence also points to the efficacy of macrolides [40]. In the event of resistance to fluoroquinolones, a 3-month therapy with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole has been suggested [10]. Table 5 summarizes therapeutic suggestions of the Giessen group. No advantage of a combination of antimicrobials and alpha-blockers [41] has been proven.

Due to the complexity of the pathogenetic mechanisms and the heterogeneity of symptoms, understanding CPPS, especially the appropriate therapeutic approach, is still a challenge and a matter of debate [5]. Up to now, the efficacy of a monotherapy has not really been proven despite a meta-analysis of many common treatments such as alpha-blockers, antibiotics, alpha-blockers and antibiotics, anti-inflammatory working substances and phytotherapy [42].

Due to this unsatisfactory situation, a multimodal therapy seems to be the best approach [43] if the above mentioned UPOINT(s) system involving all clinical domains (Table 3) is used. Symptom severity is assessed using NIH-CPSI and the patient should show a positive development, whereby a minimum 6-point drop in the total scale is considered a successful endpoint. A web-based algorithm is also available at http://www.upointmd.com. Other therapeutic approaches include psychological support in patients with enduring symptoms and depression [44] and [45], while surgical procedures in cases where an anatomical cause of obstruction is proven [6] and [11] are an ongoing matter of debate [7]. Physiotherapeutic “pelvic floor” relaxant options have been suggested, including shock-wave therapy of the prostatic area [45] and [46]. There is no evidence that therapy of prostatitis-syndrome improves sexual function. One myth is that the frequency of sexual activity may change prostatic health and sexual activity [47]. Both refraining from ejaculation and an increase in regular sexual activity with high ejaculatory frequency have been suggested as factors for improving sexual function (see Overview in 27). Also the benefit of PDE-5 inhibitors has been discussed although data analysis does not provide clear evidence of efficacy on sexual dysfunction in CPPS patients outside cohorts with predominant LUTS [48].

It is nowadays generally agreed that this condition does not require additional diagnosis or therapy. Antimicrobial therapy can be suggested to patients with raised PSA [24], but evidence-based data are lacking.

Dr. Benelli is assigned to Giessen University for “Uro-Andrology” for one year

Supported by Excellence Initiative of Hessen: LOEWE: Urogenital infection/inflammation and male infertility (MIBIE)

Diagnosis of prostatitis refers to a variety of inflammatory and non-inflammatory, symptomatic and non-symptomatic entities often not affecting the prostate gland. Prostatitis syndrome has been classified in a consensus process as infectious disease (acute and chronic), chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CPPS) and asymptomatic prostatitis [1] (Table 1). Prostatitis-like symptoms, especially pelvic pain, occur with a prevalence of about 8% [2], with severe symptoms especially in CPPS. The National Institutes of Health Chronic Prostatitis Syndrome Index (NIH-CPSI) represents world-wide the validated assessment tool for evaluating prostatitis-like symptoms [3] and [4]. Only Category IV prostatitis is asymptomatic with the diagnosis normally resulting from histological evaluation by biopsy [4].

Table 1

NIH classification system for prostatitis syndromes [1]

| Category | Nomenclature |

|---|---|

| I | Acute bacterial prostatitis |

| II | Chronic bacterial prostatitis |

| III | Chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CPPS) |

| III A | Inflammatory |

| III B | Non-inflammatory |

| IV | Asymptomatic prostatitis |

In clinical practice, 90 percent of outpatients suffer from CPPS, inflammatory or non-inflammatory disease [5] and [6]. Management of pelvic pain is a major challenge for the urologist [5]. Men with proven bacterial prostatitis need meticulous diagnostic management and therapy, some of them have to be hospitalized [6], [7], [8], [9], and [10].

This review covers accepted aspects of diagnostic procedures and therapeutic attempts in men suffering from symptomatic prostatitis and CPPS (Categories I to III).

Careful medical history (e.g. physical examination) investigating presence of fever and voiding dysfunction is fundamental. It should include scrotal evaluation and a gentle digital rectal examination without prostate massage, which is not recommended due to the risk of bacterial dissemination. The prostate is usually described as tender and swollen [6], [7], [8], and [9].

Diagnosis is based on microscopic analysis of a midstream urine specimen with evidence of leucocytes and confirmed by a microbiological culture, which is mandatory and the only laboratory examination required [7], [10], and [11]. Enterobacteriaceae, especially E. coli, are most common (Table 2) [6], [7], and [11]. Prostatic specific antigen is often increased and may be used diagnostically [7] and [9].

Table 2

Common pathogens in bacterial prostatitis (NIH I, II) [6] and [11]

| Etiologically recognized pathogens | Microorganisms of debatable significance | Fastidious microorganisms |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | Staphylococci | M. tuberculosis |

| Klebsiella sp. | Streptococci | Candida sp. |

| Proteus mirabilis | Corynebacterium sp. |

|

| Enterococcus faecalis | C. trachomatis |

|

| P. aeruginosa | U. urealyticum |

|

|

|

M. hominis |

|

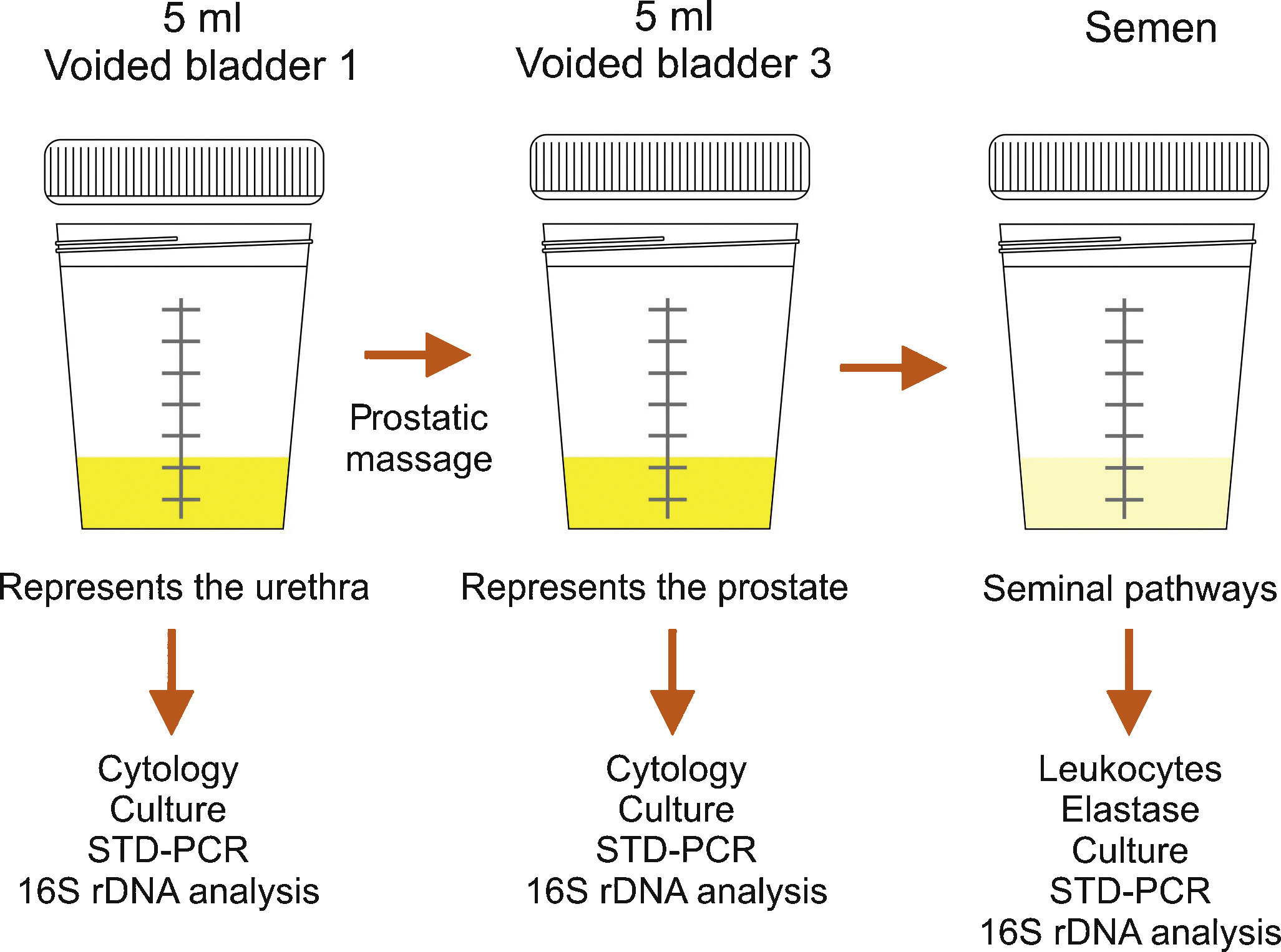

Bacteriological localization cultures are fundamental for the diagnosis of chronic bacterial prostatitis [7] and [11]. In the past, the “4-glass test” was the gold standard [13], but in the meantime, a “2-glass test”, which is a simpler and reasonably accurate alternative [14] and [15], is routinely used in the “Giessen Prostatitis Research Group”. This includes a comparative approach on a cultural basis with a 10-fold increase in voided bladder urine after prostatic massage for diagnosis of CBP (Figure 1). Normally, an ejaculate analysis for bacteriological, cytological or spermatological reasons can be added. The suggestion of the WHO [16] is to do this after passing urine (Figure 1). A good correlation of results with the “2-glass test” has been demonstrated [14] and [15]. Regarding microbiological diagnostics from the “2-glass test” and ejaculate material, a combination of culture-dependent and culture-independent methods has been shown to improve the microbial findings [17]. For bacterial culture, it is of utmost importance to process and cultivate the samples within 2-4 hours after sampling. Storage at 4 °C in the refrigerator decreases the sensitivity of culture-based tests and has to be avoided. The culture-independent tests are not affected by transportation time and consist of two consecutive PCR methods: 1) specific PCR, targeting DNA regions of common STD pathogens such as Mycoplasma genitalium, Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae (STD-PCR), and 2) broad-range PCR, targeting the 16S rRNA gene of bacteria (16S-PCR) and followed by sequencing. 16S-PCR is a highly sensitive method for detecting non-cultivable bacteria and should be applied only if the bacterial culture and the STD-PCR are negative [18]. Further advances in next generation sequencing (NGS) and a fall in the cost of sequencing techniques will soon facilitate comprehensive microbiome analysis of prostate secretions for identifying microbial communities in more detail.

Semen culture of the ejaculate alone is not sufficient for diagnosis of CBP due to a sensibility of only 50% in identifying bacteriospermia [7] and [8]. The most common pathogens are similar to acute bacterial prostatitis (Table 1); fastidious pathogens such as M tuberculosis and Candida sp. need PCR-mediated investigation in the urine [11]. Uncommon microorganisms, e.g. C. trachomatis and Mycoplasma species, may spread to the different accessory glands (see overview in [19]). Until today, proven prostatic infections have not been confirmed for chlamydiae [20]. Obviously, the possibility of urethral infection reduces the biological significance of positive chlamydial finding in post-prostatic massage urine [20]. Questionably increased IL-8 levels and evidence of antichlamydial mucosal IG-A in seminal plasma may be helpful for clarification [21]. The role of Mycoplasma species (M. hominis, M. genitalium, U. urealytium) in prostatitis remains unsettled (see overview in [19]). Recent data suggest a detection rate of 25% in urogenital secretions without an association to urogenital symptoms, depending upon the patient population.

Lower urinary tract symptoms and pelvic pain due to pathologies of the prostate have always affected quality of life in men of all ages. For years, understanding of the condition was based merely on a prostate relationship via an organ pathology involving somatic or visual tissue lesions [5] and [22]. Today, emotional, cognitive, behavioral and sexual responses are also accepted as possible trigger mechanisms for pain symptoms [4], [5], [22], and [23]. The National Institutes of Health Chronic Prostatitis Symptom Index (NIH-CPSI) represents an objective assessment tool and has been validated in many European languages [3], [4], and [22]. As a validated instrument, it is commonly used in clinical trials for measuring treatment response. In this context, the IPPS and the IIEF significantly support initial assessment and the course of disease in response to treatment [7], [8], and [24]. Additionally, the concept of phenotyping of all symptomatic patients in clinical domains is a new issue (see below) for improving therapy [23] (Table 3).

Table 3

Phenotype classification modified according to Shoskes and Nickel [23], [26], and [28]

| U | P | O | I | N | T | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urinary | Psychological | Organ specific | Infection | Neurologic/Systemic | Tenderness | Sexual dysfunction |

| Disturbed voiding | Depression | Inflammatory prostatic secretions | Infection | Instable bowel syndrome, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome | Pelvic floor spasm | Erectile, ejaculatory, orgasmic dysfunction |

The simple “2-glass test” for analyzing the number of leukocytes in VB3 [14] and [15] and an additional ejaculate analysis for counting of leucocytes [7], [8], and [16] can be used to differentiate inflammatory and non-inflammatory CPPS. Various parameters with database cut-off points for inflammatory reaction are used by different groups. There is no validated limit regarding WBCs for differentiating NIH IIIa vs IIIb forms [24]. We suggest complementary parameters in urine after prostate massage, EPS and semen (Table 4) for differentiation purposes [24].

TRUS is normally not indicated [7]. Urodynamics should be proposed to patients with LUTS to rule out bladder neck hypertrophy, bladder outlet obstruction, and vesicosphincter dyssynergia. Uroflowmetry and residual urine bladder scan may produce more sophisticated urodynamics [7]. Cystoscopy is not routinely indicated; in suspected interstitial cystitis, specific diagnostics are mandatory [7] and [11].

An association between male sexual dysfunction and prostatitis syndrome, especially CPPS, has been the subject of controversy for years [25]. Although the exact mechanisms of sexual dysfunction in CPPS have not been elucidated, recent data suggest a multifactorial origin with vascular, endocrine, psychogenic and neuromuscular causes [26]. Consensus data based on a PubMed database analysis confirmed a significant percentage of ED in men suffering from CP/CPPS between 30 to 72 percent, measured using IIEF and NIH-CPSI [27]. Clinical phenotyping of CPPS patients (UPOINT[s]) or adding a sexual dysfunction domain to the standard questionnaire might be helpful [4], [5], and [28]. When discussing etiology of ED in these cases, there are hints that psychogenic factors are mainly relevant in all patients suffering from CPPS and ED [27] and [29]. Another very important entity is the interaction between CPPS symptoms and ejaculatory dysfunction. Based on studies from Asia, premature ejaculation seems to be a significant factor in sexual dysfunction in up to 77% of patients with CPPS (see Overview in 27). It appears similarly important to us that “prostatitis” patients suffer from ejaculatory pain [30] and [31]. The presence of ejaculatory pain in CPPS seems to be associated with more severe symptoms in the NIH-CPSI [31].

Since prostatitis is common in males of reproductive age, a negative impact on semen composition, and thus on fertility, may be suspected. Unfortunately, only a few studies are available investigating different types of prostatitis. In patients with NIH type II prostatitis, a recent meta-analysis evaluated seven studies including 249 patients and 163 controls [32]. While sperm vitality, sperm total motility and the percentage of progressively motile sperm were significantly impaired, no impact was identified regarding semen volume, sperm concentration and semen liquefaction. However, the meta-analysis has to be looked at more carefully, because three studies from China are not available through PubMed. In addition, one study from China published in English looks similar to another study included in the meta-analysis from the same group and has been retracted by the editors of the original journal because of scientific misconduct. Unfortunately, one full study was not included [33]. Thus, further larger studies with adequate control groups are necessary to answer the question of whether chronic bacterial prostatitis has a negative impact on semen parameters. More studies are available investigating NIH type III prostatitis. Again, a recent meta-analysis is available on this population of patients, including a total of 12 studies with 999 patients and 455 controls [34]. The meta-analysis showed that sperm concentration, percentage of progressively motile sperm and sperm morphology of patients were significantly lower than in controls. Limitations include the lack of differentiation between type IIIA and IIIB prostatitis and the heterogeneity of recruited controls, ranging from asymptomatic men to healthy sperm donors with fully normal semen. Finally, prostatitis-like symptoms, defined as a cluster of bothersome perineal and/or ejaculatory pains or general discomfort, were not associated with any sperm parameter investigated in males of infertile couples [35]. In summary, both meta-analyses indicate significant impairment of at least some sperm parameters in patients with prostatitis compared to controls. However, whether the adverse effect on sperm parameters has any impact on fertility has not been proven so far.

Acute bacterial prostatitis is a serious infection. The main symptoms are high fever, pelvic pain and general discomfort. It can also result in septicemia and urosepsis, with elevated risk for the patient's life and mandatory hospitalization [36]. Initial antibiotic treatment is empirical and experience-based [37]. A broad-spectrum penicillin derivative with a beta-lactamase inhibitor, third-generation cephalosporin or fluoroquinolone, possibly in association with aminoglycoside, is suggested [10] and [11]. Patients without complicated symptoms may be treated with oral fluoroquinolones [37], [38], and [39]. After initial improvement and evaluation of bacterial susceptibility, appropriate oral therapy can be administered and should be performed for at least 4 weeks [24]. Some authors suggest suprapubic catheterization in the event of urinary retention to avoid a blockade of the prostate ducts by a transurethral catheter [9] and [24]. If a prostatic abscess is identified which is more than 1 cm in diameter, it should be aspirated and drained [7] and [9].

Due to their proven pharmacokinetic properties and antimicrobial spectrum, fluoroquinolones (especially levofloxacin and ciprofloxacin) are the most recommended antibiotics agents for treating chronic bacterial prostatitis [11], [37], [38], and [39]. They have a strong antimicrobial effect on the most common Gram-negative, Gram-positive and atypical pathogens. The recommended administration period is about 4 weeks [10] and [11]. Some evidence also points to the efficacy of macrolides [40]. In the event of resistance to fluoroquinolones, a 3-month therapy with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole has been suggested [10]. Table 5 summarizes therapeutic suggestions of the Giessen group. No advantage of a combination of antimicrobials and alpha-blockers [41] has been proven.

Due to the complexity of the pathogenetic mechanisms and the heterogeneity of symptoms, understanding CPPS, especially the appropriate therapeutic approach, is still a challenge and a matter of debate [5]. Up to now, the efficacy of a monotherapy has not really been proven despite a meta-analysis of many common treatments such as alpha-blockers, antibiotics, alpha-blockers and antibiotics, anti-inflammatory working substances and phytotherapy [42].

Due to this unsatisfactory situation, a multimodal therapy seems to be the best approach [43] if the above mentioned UPOINT(s) system involving all clinical domains (Table 3) is used. Symptom severity is assessed using NIH-CPSI and the patient should show a positive development, whereby a minimum 6-point drop in the total scale is considered a successful endpoint. A web-based algorithm is also available at http://www.upointmd.com. Other therapeutic approaches include psychological support in patients with enduring symptoms and depression [44] and [45], while surgical procedures in cases where an anatomical cause of obstruction is proven [6] and [11] are an ongoing matter of debate [7]. Physiotherapeutic “pelvic floor” relaxant options have been suggested, including shock-wave therapy of the prostatic area [45] and [46]. There is no evidence that therapy of prostatitis-syndrome improves sexual function. One myth is that the frequency of sexual activity may change prostatic health and sexual activity [47]. Both refraining from ejaculation and an increase in regular sexual activity with high ejaculatory frequency have been suggested as factors for improving sexual function (see Overview in 27). Also the benefit of PDE-5 inhibitors has been discussed although data analysis does not provide clear evidence of efficacy on sexual dysfunction in CPPS patients outside cohorts with predominant LUTS [48].

It is nowadays generally agreed that this condition does not require additional diagnosis or therapy. Antimicrobial therapy can be suggested to patients with raised PSA [24], but evidence-based data are lacking.

Dr. Benelli is assigned to Giessen University for “Uro-Andrology” for one year

Supported by Excellence Initiative of Hessen: LOEWE: Urogenital infection/inflammation and male infertility (MIBIE)

Diagnosis of prostatitis refers to a variety of inflammatory and non-inflammatory, symptomatic and non-symptomatic entities often not affecting the prostate gland. Prostatitis syndrome has been classified in a consensus process as infectious disease (acute and chronic), chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CPPS) and asymptomatic prostatitis [1] (Table 1). Prostatitis-like symptoms, especially pelvic pain, occur with a prevalence of about 8% [2], with severe symptoms especially in CPPS. The National Institutes of Health Chronic Prostatitis Syndrome Index (NIH-CPSI) represents world-wide the validated assessment tool for evaluating prostatitis-like symptoms [3] and [4]. Only Category IV prostatitis is asymptomatic with the diagnosis normally resulting from histological evaluation by biopsy [4].

Table 1

NIH classification system for prostatitis syndromes [1]

| Category | Nomenclature |

|---|---|

| I | Acute bacterial prostatitis |

| II | Chronic bacterial prostatitis |

| III | Chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CPPS) |

| III A | Inflammatory |

| III B | Non-inflammatory |

| IV | Asymptomatic prostatitis |

In clinical practice, 90 percent of outpatients suffer from CPPS, inflammatory or non-inflammatory disease [5] and [6]. Management of pelvic pain is a major challenge for the urologist [5]. Men with proven bacterial prostatitis need meticulous diagnostic management and therapy, some of them have to be hospitalized [6], [7], [8], [9], and [10].

This review covers accepted aspects of diagnostic procedures and therapeutic attempts in men suffering from symptomatic prostatitis and CPPS (Categories I to III).

Careful medical history (e.g. physical examination) investigating presence of fever and voiding dysfunction is fundamental. It should include scrotal evaluation and a gentle digital rectal examination without prostate massage, which is not recommended due to the risk of bacterial dissemination. The prostate is usually described as tender and swollen [6], [7], [8], and [9].

Diagnosis is based on microscopic analysis of a midstream urine specimen with evidence of leucocytes and confirmed by a microbiological culture, which is mandatory and the only laboratory examination required [7], [10], and [11]. Enterobacteriaceae, especially E. coli, are most common (Table 2) [6], [7], and [11]. Prostatic specific antigen is often increased and may be used diagnostically [7] and [9].

Table 2

Common pathogens in bacterial prostatitis (NIH I, II) [6] and [11]

| Etiologically recognized pathogens | Microorganisms of debatable significance | Fastidious microorganisms |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | Staphylococci | M. tuberculosis |

| Klebsiella sp. | Streptococci | Candida sp. |

| Proteus mirabilis | Corynebacterium sp. |

|

| Enterococcus faecalis | C. trachomatis |

|

| P. aeruginosa | U. urealyticum |

|

|

|

M. hominis |

|

Bacteriological localization cultures are fundamental for the diagnosis of chronic bacterial prostatitis [7] and [11]. In the past, the “4-glass test” was the gold standard [13], but in the meantime, a “2-glass test”, which is a simpler and reasonably accurate alternative [14] and [15], is routinely used in the “Giessen Prostatitis Research Group”. This includes a comparative approach on a cultural basis with a 10-fold increase in voided bladder urine after prostatic massage for diagnosis of CBP (Figure 1). Normally, an ejaculate analysis for bacteriological, cytological or spermatological reasons can be added. The suggestion of the WHO [16] is to do this after passing urine (Figure 1). A good correlation of results with the “2-glass test” has been demonstrated [14] and [15]. Regarding microbiological diagnostics from the “2-glass test” and ejaculate material, a combination of culture-dependent and culture-independent methods has been shown to improve the microbial findings [17]. For bacterial culture, it is of utmost importance to process and cultivate the samples within 2-4 hours after sampling. Storage at 4 °C in the refrigerator decreases the sensitivity of culture-based tests and has to be avoided. The culture-independent tests are not affected by transportation time and consist of two consecutive PCR methods: 1) specific PCR, targeting DNA regions of common STD pathogens such as Mycoplasma genitalium, Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae (STD-PCR), and 2) broad-range PCR, targeting the 16S rRNA gene of bacteria (16S-PCR) and followed by sequencing. 16S-PCR is a highly sensitive method for detecting non-cultivable bacteria and should be applied only if the bacterial culture and the STD-PCR are negative [18]. Further advances in next generation sequencing (NGS) and a fall in the cost of sequencing techniques will soon facilitate comprehensive microbiome analysis of prostate secretions for identifying microbial communities in more detail.

Semen culture of the ejaculate alone is not sufficient for diagnosis of CBP due to a sensibility of only 50% in identifying bacteriospermia [7] and [8]. The most common pathogens are similar to acute bacterial prostatitis (Table 1); fastidious pathogens such as M tuberculosis and Candida sp. need PCR-mediated investigation in the urine [11]. Uncommon microorganisms, e.g. C. trachomatis and Mycoplasma species, may spread to the different accessory glands (see overview in [19]). Until today, proven prostatic infections have not been confirmed for chlamydiae [20]. Obviously, the possibility of urethral infection reduces the biological significance of positive chlamydial finding in post-prostatic massage urine [20]. Questionably increased IL-8 levels and evidence of antichlamydial mucosal IG-A in seminal plasma may be helpful for clarification [21]. The role of Mycoplasma species (M. hominis, M. genitalium, U. urealytium) in prostatitis remains unsettled (see overview in [19]). Recent data suggest a detection rate of 25% in urogenital secretions without an association to urogenital symptoms, depending upon the patient population.

Lower urinary tract symptoms and pelvic pain due to pathologies of the prostate have always affected quality of life in men of all ages. For years, understanding of the condition was based merely on a prostate relationship via an organ pathology involving somatic or visual tissue lesions [5] and [22]. Today, emotional, cognitive, behavioral and sexual responses are also accepted as possible trigger mechanisms for pain symptoms [4], [5], [22], and [23]. The National Institutes of Health Chronic Prostatitis Symptom Index (NIH-CPSI) represents an objective assessment tool and has been validated in many European languages [3], [4], and [22]. As a validated instrument, it is commonly used in clinical trials for measuring treatment response. In this context, the IPPS and the IIEF significantly support initial assessment and the course of disease in response to treatment [7], [8], and [24]. Additionally, the concept of phenotyping of all symptomatic patients in clinical domains is a new issue (see below) for improving therapy [23] (Table 3).

Table 3

Phenotype classification modified according to Shoskes and Nickel [23], [26], and [28]

| U | P | O | I | N | T | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urinary | Psychological | Organ specific | Infection | Neurologic/Systemic | Tenderness | Sexual dysfunction |

| Disturbed voiding | Depression | Inflammatory prostatic secretions | Infection | Instable bowel syndrome, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome | Pelvic floor spasm | Erectile, ejaculatory, orgasmic dysfunction |

The simple “2-glass test” for analyzing the number of leukocytes in VB3 [14] and [15] and an additional ejaculate analysis for counting of leucocytes [7], [8], and [16] can be used to differentiate inflammatory and non-inflammatory CPPS. Various parameters with database cut-off points for inflammatory reaction are used by different groups. There is no validated limit regarding WBCs for differentiating NIH IIIa vs IIIb forms [24]. We suggest complementary parameters in urine after prostate massage, EPS and semen (Table 4) for differentiation purposes [24].

TRUS is normally not indicated [7]. Urodynamics should be proposed to patients with LUTS to rule out bladder neck hypertrophy, bladder outlet obstruction, and vesicosphincter dyssynergia. Uroflowmetry and residual urine bladder scan may produce more sophisticated urodynamics [7]. Cystoscopy is not routinely indicated; in suspected interstitial cystitis, specific diagnostics are mandatory [7] and [11].

An association between male sexual dysfunction and prostatitis syndrome, especially CPPS, has been the subject of controversy for years [25]. Although the exact mechanisms of sexual dysfunction in CPPS have not been elucidated, recent data suggest a multifactorial origin with vascular, endocrine, psychogenic and neuromuscular causes [26]. Consensus data based on a PubMed database analysis confirmed a significant percentage of ED in men suffering from CP/CPPS between 30 to 72 percent, measured using IIEF and NIH-CPSI [27]. Clinical phenotyping of CPPS patients (UPOINT[s]) or adding a sexual dysfunction domain to the standard questionnaire might be helpful [4], [5], and [28]. When discussing etiology of ED in these cases, there are hints that psychogenic factors are mainly relevant in all patients suffering from CPPS and ED [27] and [29]. Another very important entity is the interaction between CPPS symptoms and ejaculatory dysfunction. Based on studies from Asia, premature ejaculation seems to be a significant factor in sexual dysfunction in up to 77% of patients with CPPS (see Overview in 27). It appears similarly important to us that “prostatitis” patients suffer from ejaculatory pain [30] and [31]. The presence of ejaculatory pain in CPPS seems to be associated with more severe symptoms in the NIH-CPSI [31].

Since prostatitis is common in males of reproductive age, a negative impact on semen composition, and thus on fertility, may be suspected. Unfortunately, only a few studies are available investigating different types of prostatitis. In patients with NIH type II prostatitis, a recent meta-analysis evaluated seven studies including 249 patients and 163 controls [32]. While sperm vitality, sperm total motility and the percentage of progressively motile sperm were significantly impaired, no impact was identified regarding semen volume, sperm concentration and semen liquefaction. However, the meta-analysis has to be looked at more carefully, because three studies from China are not available through PubMed. In addition, one study from China published in English looks similar to another study included in the meta-analysis from the same group and has been retracted by the editors of the original journal because of scientific misconduct. Unfortunately, one full study was not included [33]. Thus, further larger studies with adequate control groups are necessary to answer the question of whether chronic bacterial prostatitis has a negative impact on semen parameters. More studies are available investigating NIH type III prostatitis. Again, a recent meta-analysis is available on this population of patients, including a total of 12 studies with 999 patients and 455 controls [34]. The meta-analysis showed that sperm concentration, percentage of progressively motile sperm and sperm morphology of patients were significantly lower than in controls. Limitations include the lack of differentiation between type IIIA and IIIB prostatitis and the heterogeneity of recruited controls, ranging from asymptomatic men to healthy sperm donors with fully normal semen. Finally, prostatitis-like symptoms, defined as a cluster of bothersome perineal and/or ejaculatory pains or general discomfort, were not associated with any sperm parameter investigated in males of infertile couples [35]. In summary, both meta-analyses indicate significant impairment of at least some sperm parameters in patients with prostatitis compared to controls. However, whether the adverse effect on sperm parameters has any impact on fertility has not been proven so far.