Context

Chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS) is a common condition that causes severe symptoms, bother, and quality-of-life impact in the 8.2% of men who are believed to be affected. Research suggests a complex pathophysiology underlying this syndrome that is mirrored by its heterogeneous clinical presentation. Management of patients diagnosed with CP/CPPS has always been a formidable task in clinical practice. Due to its enigmatic etiology, a plethora of clinical trials failed to identify an efficient monotherapy.

Objective

A comprehensive review of published randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on the treatment of CP/CPPS and practical best evidence recommendations for management.

Evidence acquisition

Medline and the Cochrane database were screened for RCTs on the treatment of CP/CPPS from 1998 to December 2014, using the National Institutes of Health Chronic Prostatitis Symptom Index as an objective outcome measure. Published data in concert with expert opinion were used to formulate a practical best evidence statement for the management of CP/CPPS.

Evidence synthesis

Twenty-eight RCTs identified were eligible for this review and presented. Trials evaluating antibiotics, α-blockers, anti-inflammatory and immune-modulating substances, hormonal agents, phytotherapeutics, neuromodulatory drugs, agents that modify bladder function, and physical treatment options failed to reveal a clear therapeutic benefit. With its multifactorial pathophysiology and its various clinical presentations, the management of CP/CPPS demands a phenotypic-directed approach addressing the individual clinical profile of each patient. Different categorization algorithms have been proposed. First studies applying the UPOINTs classification system provided promising results. Introducing three index patients with CP/CPPS, we present practical best evidence recommendations for management.

Conclusions

Our current understanding of the pathophysiology underlying CP/CPPS resulting in this highly variable syndrome does not speak in favor of a monotherapy for management. No efficient monotherapeutic option is available. The best evidence-based management of CP/CPPS strongly suggests a multimodal therapeutic approach addressing the individual clinical phenotypic profile.

Patient summary

Chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome presents a variable syndrome. Successful management of this condition is challenging. It appears that a tailored treatment strategy addressing individual patient characteristics is more effective than one single therapy.

Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) and pelvic pain due to pathologies of the prostate have always considerably affected quality of life of men of all ages. Epidemiologic data suggest that the prevalence of prostatitis-like symptoms is comparable with ischemic heart disease and diabetes mellitus. The rate of prostatitis-like symptoms ranges from 2.2% to 9.7%, with a mean prevalence of 8.2% [1] .

In the late 1990s, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) established a consensus definition and classification system for prostatitis [2] . It has been accepted internationally in both clinical practice and research ( Table 1 ). Prostatitis syndromes comprise infectious forms (acute and chronic), the chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CPPS), and asymptomatic prostatitis [2] . In <10% of patients with prostatitis syndrome, a causative uropathogenic organism can be detected. An acute bacterial episode will lead to chronic bacterial prostatitis in 10% and to CPPS in a further 10% [3] . CPPS accounts for most of the prostatitis-like symptoms in >90% of men.

Table 1 National Institutes of Health classification system for prostatitis syndromes

| Category | Nomenclature |

|---|---|

| I | Acute bacterial prostatitis |

| II | Chronic bacterial prostatitis |

| III | Chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome |

| IIIA | Inflammatory |

| IIIB | Noninflammatory |

| IV | Asymptomatic prostatitis |

The National Institutes of Health Chronic Prostatitis Symptom Index (NIH-CPSI) presents an objective assessment tool and outcome measure for prostatitis-like symptoms [4] and [5]. The introduction of a generally accepted classification system and an objective outcome measure led to a plethora of clinical trials that made one particular point clear. Although the treatment of bacterial prostatitis obviously relies on the adequate use of antimicrobial agents, successful management of CPPS has always been a formidable task. The complex and heterogeneous pathophysiology of CPPS is poorly understood. Consequently, an effective monotherapy is not available, which makes the management of CPPS challenging for both physicians and patients. Clinical trials were not able to identify a monotherapy with significant clinical efficacy. A meta-analysis evaluating data of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) using the NIH-CPSI as a common outcome measure failed to derive a guideline statement on the treatment of this bothersome condition [6] and [7].

The dilemma of limited success of clinical trials prompted us to provide a comprehensive review with expert interpretations of the available literature to formulate best practice recommendations. Introducing index patients diagnosed with CPPS, we demonstrate how these recommendations might be applied in clinical practice. The main objective of this review is to present best practice recommendations for the management of CPPS (NIH type III).

We performed a systematic review of the literature in the PubMed and Cochrane database according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis statement [8] . We searched for RCTs and meta-analyses on the treatment of chronic prostatitis CP/CPPS from January 1988 to December 2014. A detailed description of the search strategy is presented in Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Figure 1. In addition, references of review articles were screened for possibly missed articles.

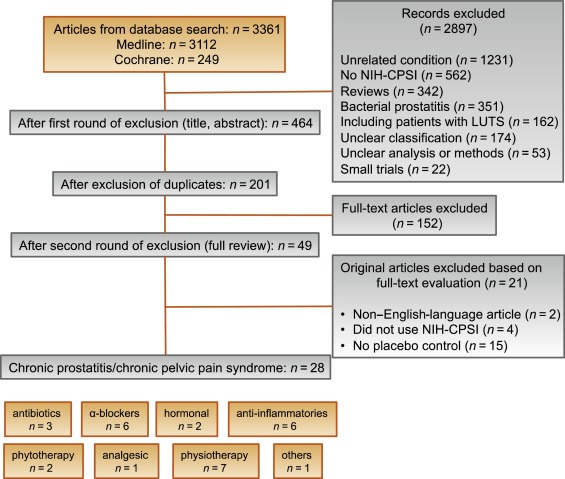

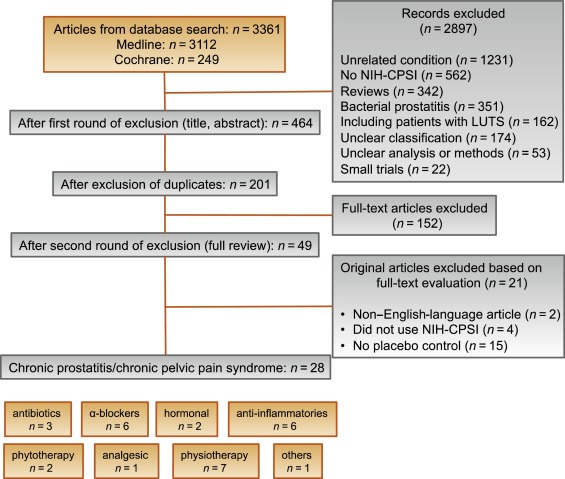

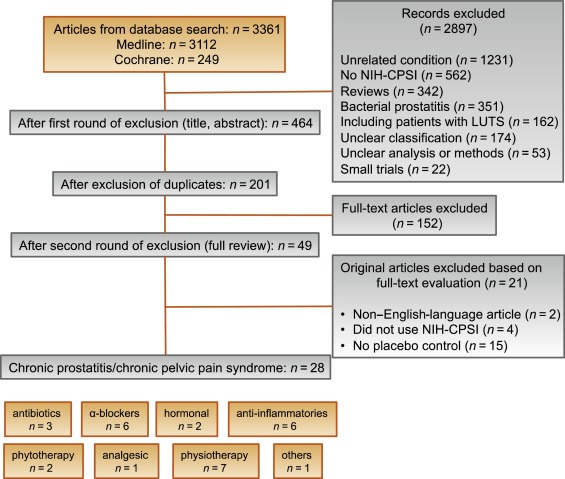

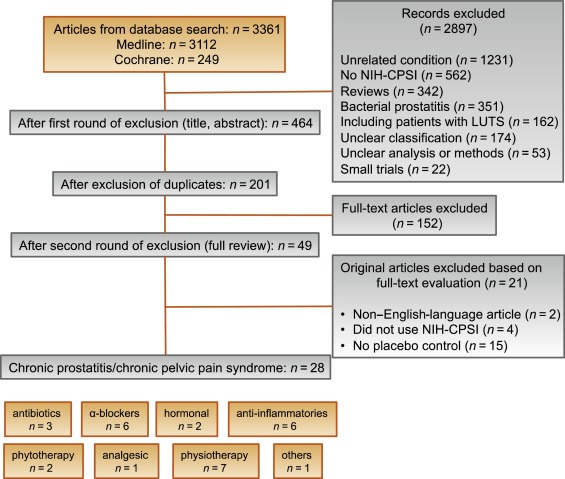

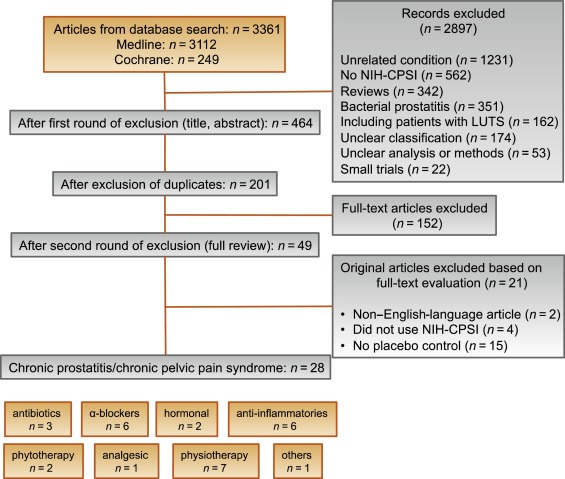

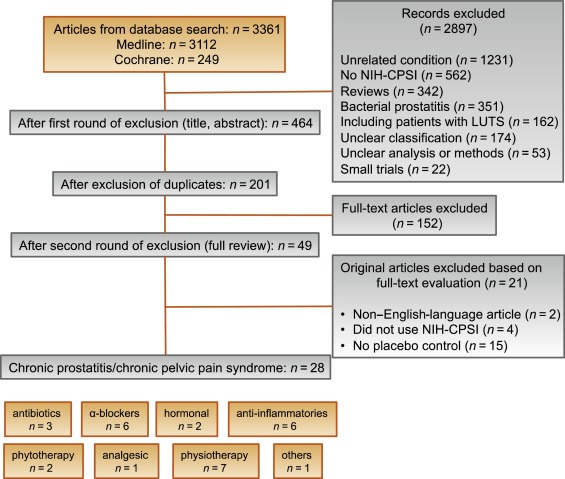

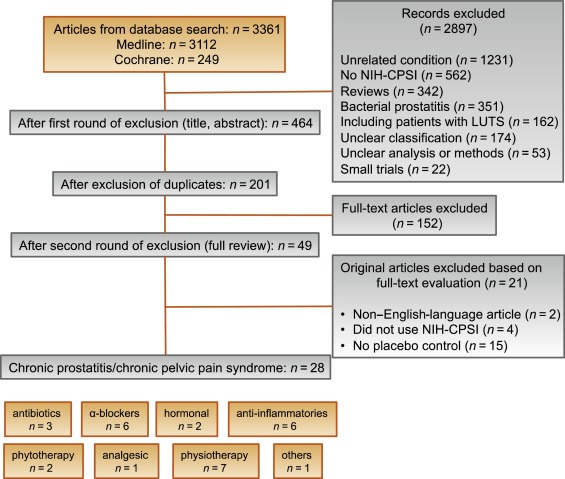

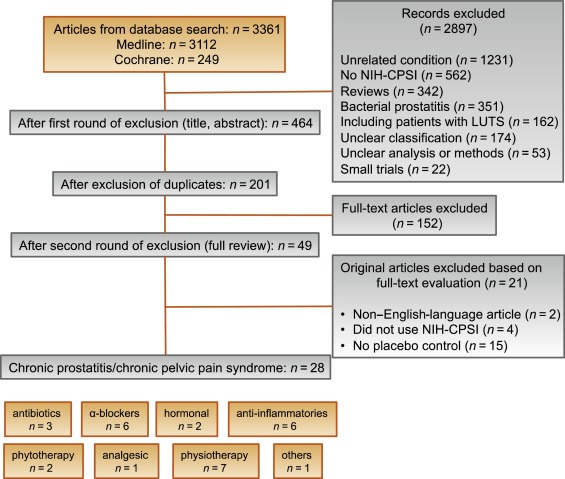

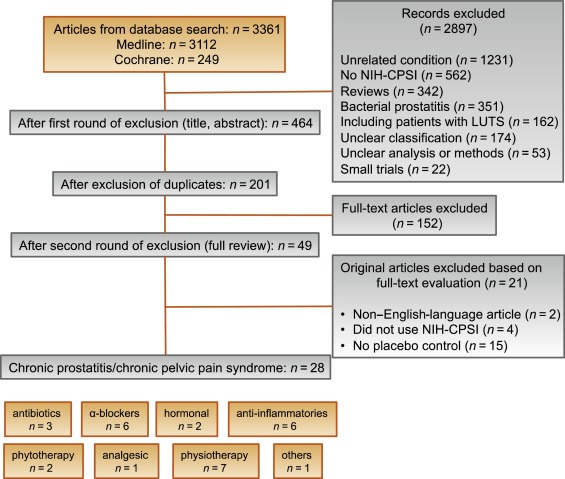

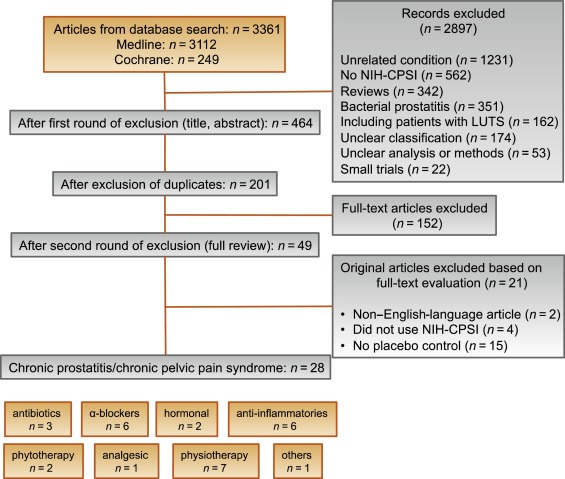

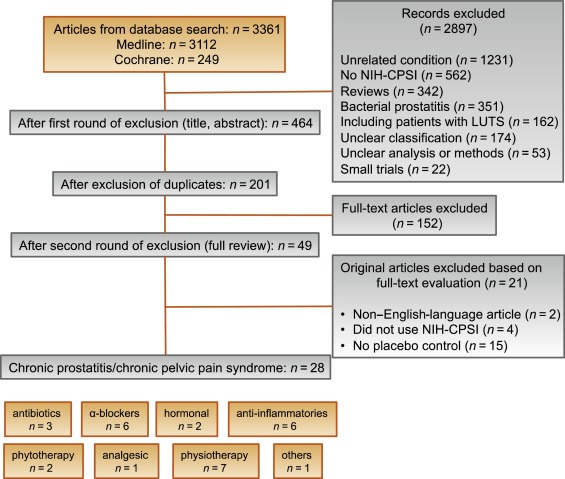

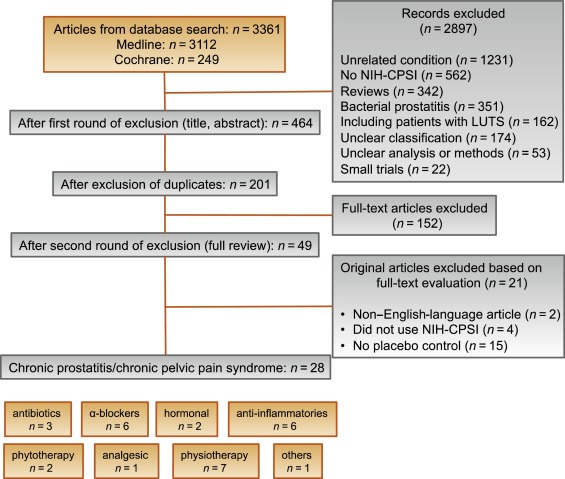

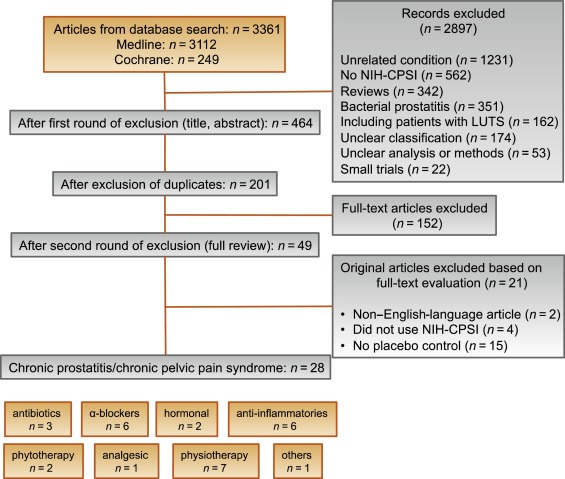

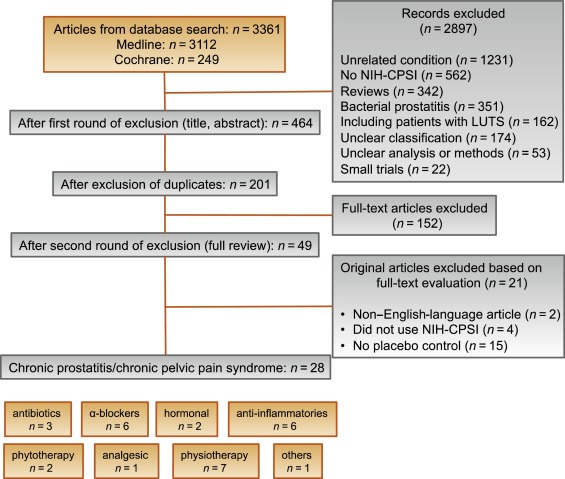

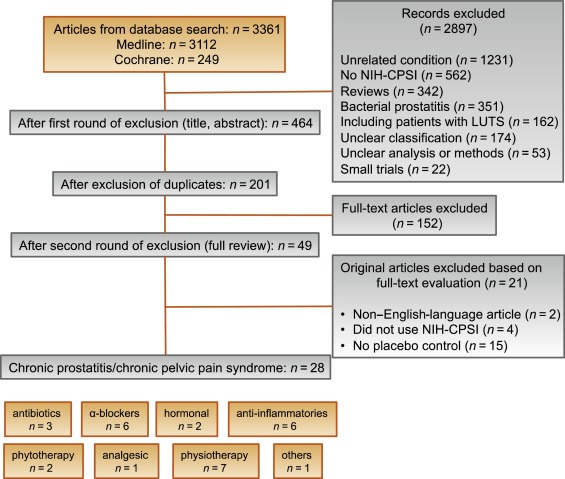

RCTs published in English were selected if they met the following criteria: (1) RCTs (comparisons; placebo or sham controlled; no invasive procedures), (2) patients were classified as CP category IIIA or IIIB according to the NIH consensus definition, (3) at least 10 individuals were evaluated per treatment arm, and (4) the NIH-CPSI score was utilized as an outcome measure for CP/CPPS. Articles were first reviewed independently by two authors to determine their eligibility for inclusion. With consensus the article moved on to the next round, and if the first two reviewers disagreed, a third reviewer was included to reach unanimous agreement ( Fig. 1 ).

The systematic literature review revealed 28 RCTs for the therapy of CPPS eligible for inclusion. Two performed meta-analyses published in the last 4 yr on this subject [6] and [7] were not able to provide any relevant useful information for clinical practice. We realized that no significant clinical data from recently published RCTs could be included since the last meta-analyses were performed (Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Fig. 1). Another attempt to evaluate the available clinical data would add nothing to the literature and not provide any more guidance to practicing urologists. Consequently, we present the available literature on treatment modalities to outline the scientific dilemma and formulate best practice statements that used published data in concert with expert opinion. This does not use formal meta-analysis. We attempted to outline the complete management of CPPS including diagnostic assessment and treatment.

The introduction of index patients demonstrates how to implement the presented recommendations in clinical practice. After the conception of each index patient, the relevant symptoms were identified and treatment options were discussed. For this purpose, every author received the different case presentations and independently analyzed symptoms, treatment targets, and therapeutic options. The results were returned to G.M., who collected responses and pointed out discrepancies. After discussions we agreed on the points presented in tables.

CP/CPPS (NIH category III) is defined as urologic pain or discomfort in the pelvic region, associated with urinary symptoms and/or sexual dysfunction, lasting for at least 3 of the previous 6 mo. Differential diagnoses of pelvic pain such as urinary tract infection, cancer, anatomic abnormalities, or neurologic disorders need to be excluded. CP/CPPS is subclassified as an inflammatory type (NIH category IIIA) and a noninflammatory type (NIH category IIIB) according to the presence of leukocytes in prostatic samples [2] .

Patients with prostatitis-like symptoms report perineal, testicular, and penile discomfort. Pain may also be accompanied by LUTS and sexual dysfunction. Symptoms persist for at least 3 mo. CP/CPPS is often associated with negative cognitive, behavioral, sexual, or emotional consequences that should be addressed as part of the medical history. The correct classification demands a systematic diagnostic assessment.

The first step is to assess the severity and impact of symptoms by utilizing the NIH-CPSI (level of evidence 2b; grade of recommendation B) [9] . The NIH-CPSI presents an objective assessment tool and outcome measure for prostatitis-like symptoms [4] and [5]. The symptom-scoring questionnaire is a reliable tool for basic evaluation and therapeutic monitoring. This self-administered questionnaire asks nine questions that are scored in three domains: pain, urinary symptoms, and the impact on quality of life. Severity categories have been proposed, and a 6-point decline from the baseline total score is considered the threshold for a positive therapeutic response. In addition, the International Prostate Symptom Score [10] and the International Index of Erectile Function [11] present optional valuable outcome measures to evaluate the current condition and course of disease in response to treatment.

Physical examination of the abdomen, genitalia, perineum, and prostate is mandatory. Additional evaluation of myofascial trigger points and/or musculoskeletal dysfunction of the pelvis and pelvic floor may be helpful.

Microbiologic localization cultures are the standard laboratory method for identifying chronic bacterial prostatitis (NIH type II). The four-glass test according to Meares and Stamey is recommended [12] . First voided urine, midstream urine, expressed prostatic secretion, and post–prostate massage urine are analyzed for identification and quantification of pathogens and inflammation. A simpler two-glass test is also possible as a reasonably accurate screen for initial evaluation. It involves the investigation of pre– and post–prostate massage urine. It was shown to correlate well with the four-glass test [13] . The four-glass test or two-glass test are used to exclude bacterial infection. Although the detection of leukocytes confirms CP/CPPS type IIIA, in type IIIB no signs of inflammation are observed. The clinical value of this categorization has never been validated. Semen cultures of the ejaculate alone are not sufficient for diagnosis.

Laboratory testing including complete blood count, inflammatory parameters, and serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) is not recommended to diagnose CP/CPPS. PSA may be considered if patients are at risk for prostate cancer. Transrectal ultrasound is not useful for the diagnosis, unless there is a specific indication in selected patients such as intraprostatic abscess, calcification, or dilatation of seminal vesicles.

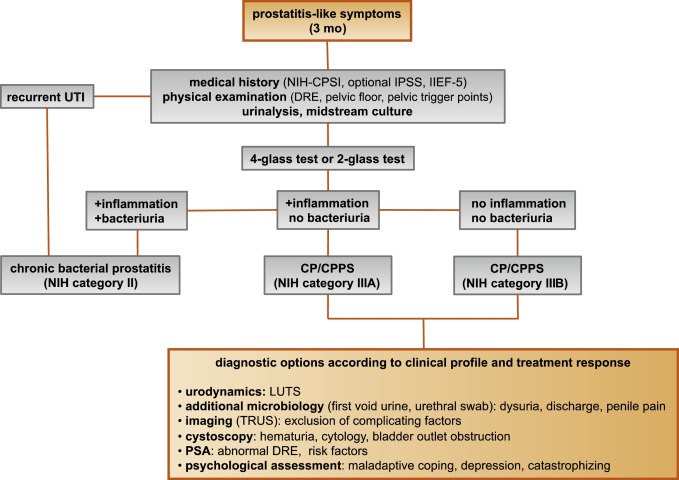

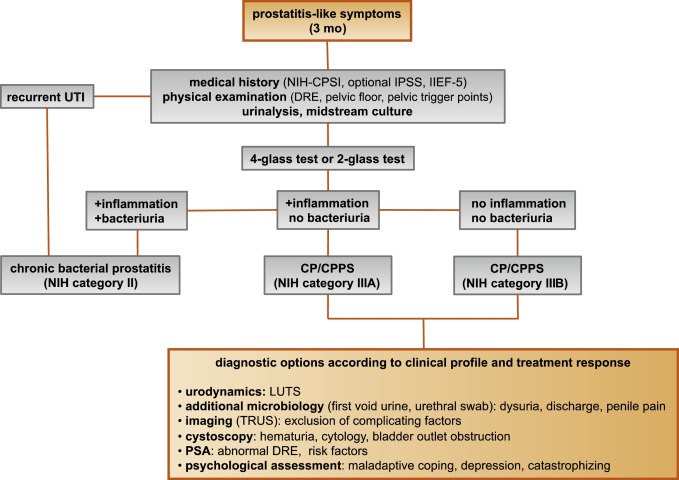

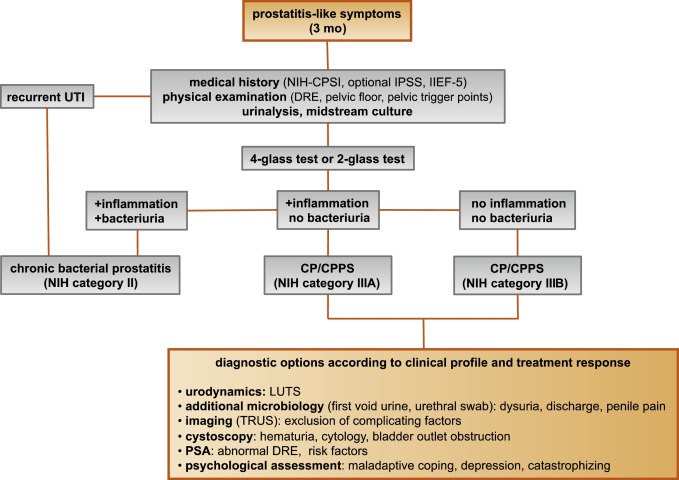

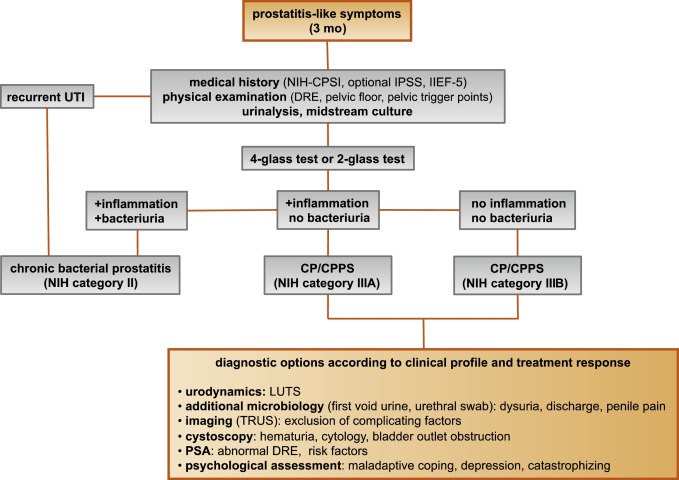

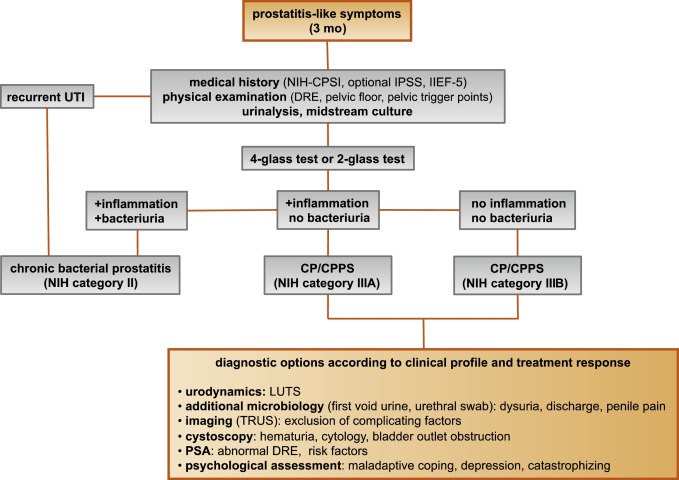

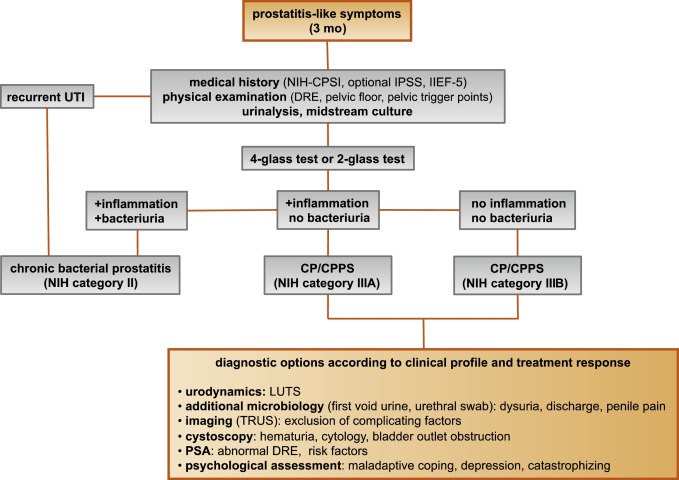

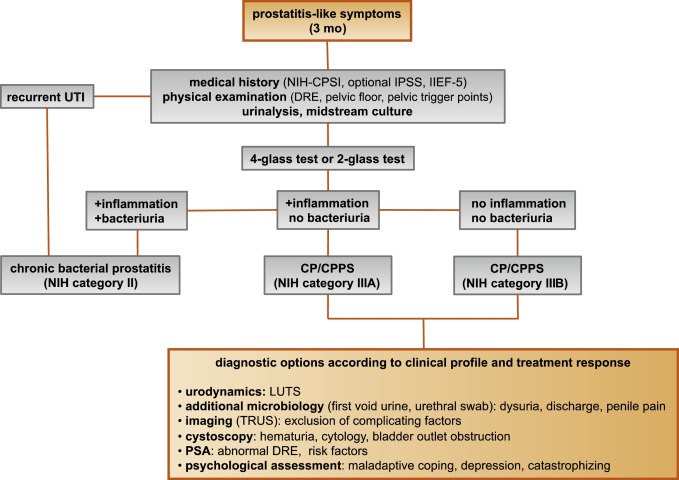

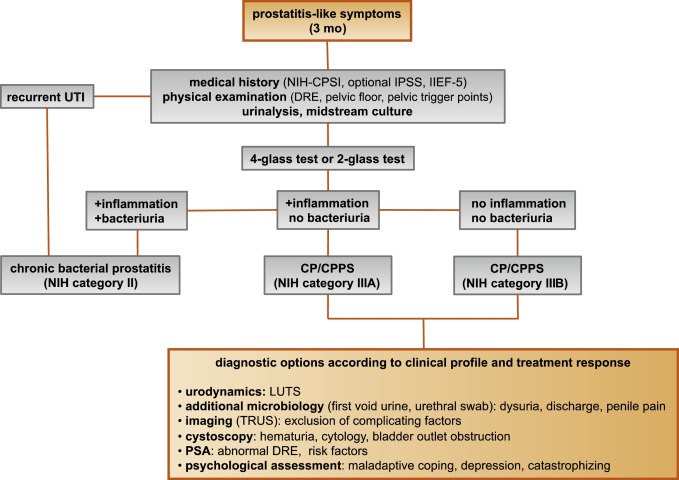

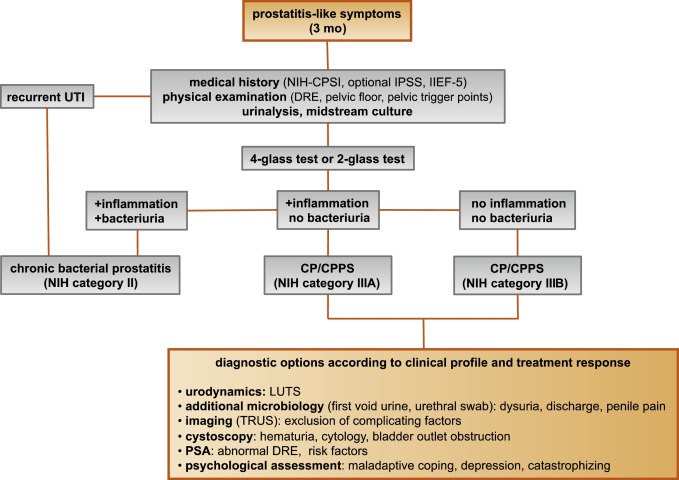

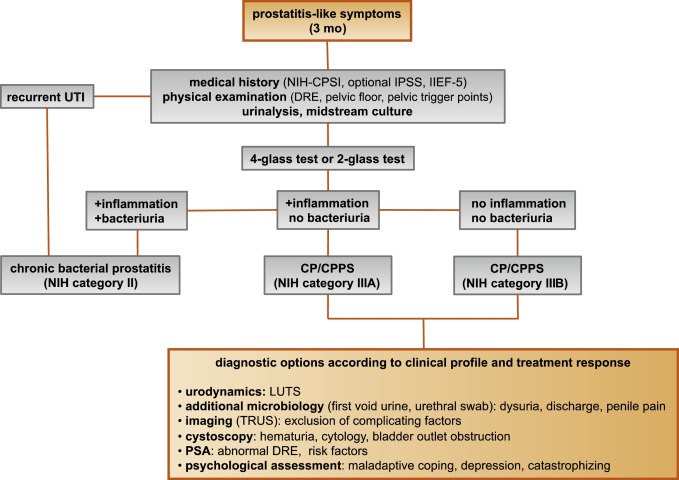

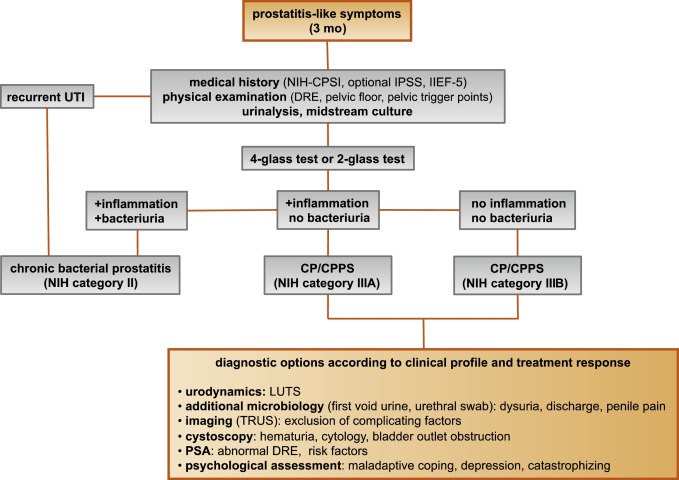

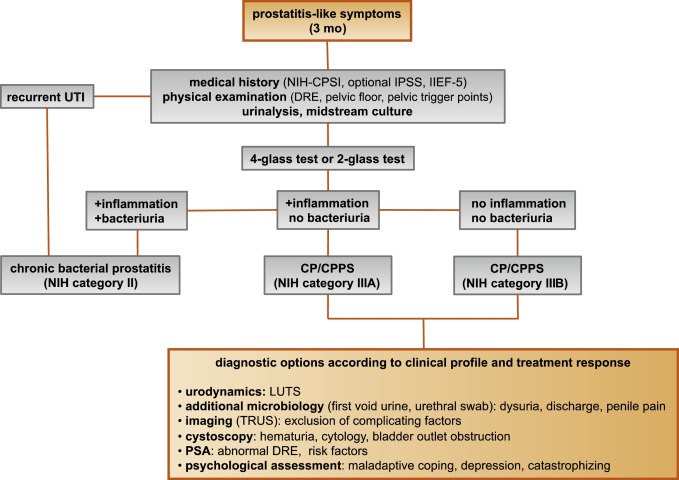

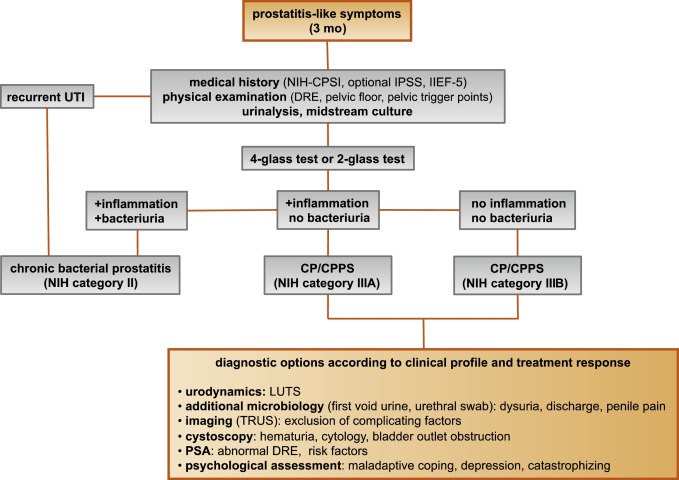

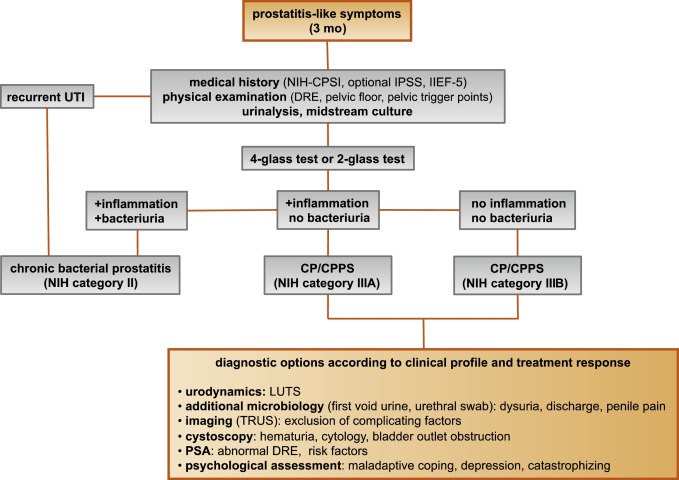

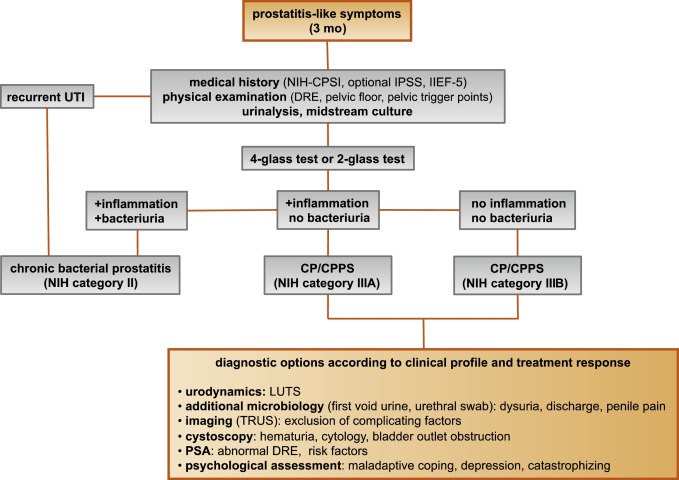

Urodynamic studies may be considered in selected patients with voiding/storage symptoms suggestive of bothersome LUTS. Cystoscopy or retrograde urethrography may be considered to rule out bladder outlet obstruction. Figure 2 shows a diagnostic algorithm for patients with prostatitis-like symptoms [9] and [14].

Due to the heterogeneity and the still elusive pathophysiology of CP/CPPS, the establishment of effective treatment modalities remains challenging. A multitude of clinical trials failed to identify an efficient primary treatment. Here we present published randomized placebo- or sham-controlled clinical trials using the NIH-CPSI as an objective outcome measure ( Table 2 ).

Table 2 Included randomized clinical trials for treatment of chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome

| Treatment | Duration | Patients, n | Basic mean NIH-CPSI total score | Mean change | Significance | Jadad total score | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibiotics | |||||||

| Ciprofloxacin vs tamsulosin vs combination vs placebo |

6 wk | 49 49 49 49 |

24.2 24.6 25.3 25.0 |

−6.2 −4.4 −4.1 −.4 |

No (p > 0.05) |

≥3 | [15] |

| Levofloxacin vs placebo |

6 wk | 45 35 |

24.4 21.3 |

−5.6 −3.1 |

No (p > 0.05) |

≥3 | [16] |

| Tetracycline vs placebo |

12 wk | 24 24 |

35.6 NR |

−8.5 NR |

Yes (p < 0.01) |

<3 | [17] |

| α-Blockers | |||||||

| Tamsulosin vs placebo |

6 wk | 27 30 |

26.4 26.2 |

−9.1 −5.5 |

Yes (p < 0.05) |

≥3 | [19] |

| Alfuzosin vs placebo |

12 wk | 138 134 |

23.8 25.1 |

−7.1 −6.5 |

No (p > 0.05) |

≥3 | [20] |

| Silodosin 8 mg vs silodosin 4 mg vs placebo |

12 wk | 45 52 54 |

26.8 26.0 27.9 |

−10.2 −12.1 −8.5 |

Yes (p < 0.05) |

≥3 | [18] |

| Doxazosin vs DIT vs placebo |

24 wk | 30 30 30 |

23.1 21.9 22.9 |

−10.6 −10.2 −0.7 |

Yes (p < 0.001) |

<3 | [23] |

| Terazosin vs placebo |

14 wk | 43 43 |

25.1 27.2 |

−14.3 −10.2 |

Yes (p = 0.01) |

<3 | [22] |

| Alfuzosin vs placebo |

24 wk | 17 20 |

26.0 23.0 |

−9.9 −3.8 |

Yes (p = 0.01) |

<3 | [21] |

| Anti-inflammatories | |||||||

| Rofecoxib 25 mg vs rofecoxib 50 mg vs placebo |

6 wk | 53 49 59 |

22.5 20.5 22.9 |

−4.9 −6.2 −4.2 |

No (p > 0.05) |

≥3 | [24] |

| Prednisolone vs placebo |

4 wk | 9 12 |

25.5 23.4 |

NR | No (p > 0.05) |

≥3 | [26] |

| Celecoxib vs placebo |

6 wk | 32 32 |

23.9 24.3 |

−8.0 −4.8 |

Yes (p < 0.015) |

≥3 | [27] |

| Tanezumab vs placebo |

Single dose | 30 32 |

25.0 26.0 |

−4.3 −2.8 |

No (p > 0.05) |

<3 | [25] |

| Zafirlukast vs placebo |

4 wk | 10 7 |

22.4 23.4 |

−4.6 −8.1 |

No (p > 0.05) |

≥3 | [28] |

| OM-89 vs placebo |

12 mo | 94 91 |

21.8 23.0 |

−10.4 −9.8 |

No (p > 0.05) |

≥3 | [29] |

| Hormonal agents | |||||||

| Finasteride vs placebo |

24 wk | 33 31 |

20.1 22.5 |

−3.0 −0.8 |

No (p > 0.05) |

≥3 | [30] |

| Mepartricin vs placebo |

60 d | 13 13 |

25.0 25.0 |

−15.0 −5.0 |

Yes (p < 0.01) |

≥3 | [31] |

| Phytotherapy | |||||||

| Cernilton vs placebo |

12 wk | 70 69 |

19.3 20.3 |

−7.7 −5.2 |

Yes (p < 0.05) |

≥3 | [33] |

| Quercetin vs placebo |

4 wk | 15 13 |

21.0 20.2 |

−7.9 −1.4 |

Yes (p < 0.01) |

≥3 | [32] |

| Neuromodulation | |||||||

| Pregabalin vs placebo |

6 wk | 218 106 |

26.2 25.9 |

−6.5 −4.3 |

No (p > 0.05) |

≥3 | [34] |

| Modulation of bladder physiology | |||||||

| Pentosan polysulfate vs placebo |

16 wk | 51 49 |

27.1 25.8 |

−5.9 −3.2 |

No (p > 0.05) |

≥3 | [36] |

| Physical therapy | |||||||

| GTM vs MPT |

10 wk | 11 12 |

25.8 33.5 |

−6.8 −14.4 |

No (p > 0.05) |

≥3 | [37] |

| PTNS vs sham |

12 wk | 45 44 |

23.6 22.8 |

−13.4 −1.4 |

Yes (p < 0.001) |

<3 | [38] |

| Acupuncture vs sham |

10 wk | 44 45 |

24.8 25.2 |

−10.3 −6.2 |

Yes (p < 0.05) |

≥3 | [39] |

| Electroacupuncture vs sham vs control |

6 wk | 12 12 12 |

26.9 25.5 28.0 |

−9.5 −3.5 −3.5 |

Yes (p < 0.001) |

≥3 | [40] |

| ESWT vs sham |

4 wk | 30 30 |

23.2 25.1 |

−3.5 −0.1 |

Yes (p < 0.05) |

≥3 | [41] |

| Aerobic exercise vs sham |

18 wk | 52 51 |

21.9 23.0 |

−7.4 −4.8 |

Yes (p < 0.05) |

<3 | [43] |

| SEMT vs sham |

16 wk | 30 30 |

25.8 25.2 |

−7.2 −4.6 |

No (p > 0.05) |

≥3 | [42] |

DIT = doxazosin plus ibuprofen plus thiocolchicoside; ESWT = extracorporeal shock wave therapy; GTM = global therapeutic massage; MPT = myofascial physical therapy; NIH-CPSI = National Institutes of Health Chronic Prostatitis Symptom Index; PTNS = posterior tibial nerve stimulation; SEMT = sono-electro-magnetic therapy.

Antibiotics have been proposed as an option for the treatment of CP/CPPS. But recommendations were based on empirical experience rather than evidence-based studies. Three RCTs were eligible for inclusion. Six-week courses of therapy with ciprofloxacin (500 mg 2 times per day) [15] or levofloxacin (500 mg 4 times per day) [16] did not result in a statistically significant treatment response measured by the NIH-CPSI compared with placebo. Both studies were of good quality but apparently underpowered. The clinical trial by Zhou et al compared the efficiency of a treatment with tetracycline (500 mg 2 times per day) over 12 wk versus placebo [17] . Despite some quality issues, the authors report a significant mean decrease of 18.5 points in the NIH-CPSI after treatment. Altogether the available RCTs failed to support the recommendation to use antimicrobial agents as a primary treatment option.

Seven RCTs investigating the benefit of a monotherapy with α-adrenergic receptor blockers versus placebo met the criteria for inclusion [15], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], and [23]. The outcomes regarding clinical efficiency determined by NIH-CPSI were quite heterogeneous. Smaller trials evaluating a course of at least 12 wk with different α-blockers provided evidence for positive clinical response [18], [21], [22], and [23], whereas most studies analyzing a shorter duration of 6 wk did not confirm a therapeutic benefit. Of note, clinical trials testing the α-blocker tamsulosin versus placebo over 6 wk in a comparable study population with similar baseline characteristics revealed different clinical outcomes. On the one hand, the study by Alexander et al [15] failed to prove clinical efficiency; on the other hand, the trial by Nickel and colleagues supported the use of tamsulosin [19] . Due to the heterogeneity of published data, α-blockers cannot be recommended as first-line monotherapy. However, a prolonged treatment of 12 wk in patients with bothersome LUTS and no prior treatment with α-blockers may be considered in a multimodal therapeutic regimen.

A role of inflammation and immune dysfunction has been proposed for the pathophysiology of CPPS and appears to be evident for CP/CPPS NIH category IIIA. Five RCTs have been included that evaluated the therapeutic effect of anti-inflammatory agents [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], and [29]. Various approaches have been subjected to clinical trials. Interestingly, only two studies exclusively analyzed category type IIIA. Among the two trials investigating the cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors rofecoxib (25 mg or 50 mg 4 times per day) [24] and celecoxib (200 mg 4 times per day) [27] over 6 wk compared with placebo, only the study by Zhao et al was able to reveal clinical efficiency of celecoxib in patients diagnosed with CPPS type IIIA. But this treatment response was limited to the duration of therapy. Two weeks after treatment, no clinical improvement was observed.

A reducing course of oral prednisolone over 4 wk failed to demonstrate therapeutic efficiency [26] . Neither tanezumab [25] , a humanized monoclonal antibody directed against nerve growth factor, nor zafirlukast [28] , a leukotriene antagonist, were able to demonstrate superiority over placebo. In addition, OM-89, a modified preparation of lysed pathogenic Escherichia coli, was evaluated as an immunostimulating agent for the treatment of patients with CP/CPPS [29] . Again, no statistically significant difference was observed between treatment arm and placebo group with regard to clinical efficacy. To conclude, clinical trials strongly suggest that a monotherapy with anti-inflammatory or immunomodulating agents is not effective.

Two RCTs investigating the impact of hormonal modulation on prostatitis-like symptoms in patients diagnosed with CP/CPPS were selected for inclusion. The clinical trial by Nickel et al evaluated the efficiency of the specific type II 5α-reductase inhibitor finasteride versus placebo in patients with CP/CPPS category IIIA [30] . It represents a standard treatment for LUTS in patients with BPH, but finasteride (5 mg 4 times per day) over 6 mo was not able to significantly improve the clinical outcome in this study population. Another clinical trial by De Rose et al investigated the role of mepartricin, a compound known to decrease estrogen levels in the prostate [31] . This small trial reported a significant clinical improvement measured by the NIH-CPSI after a course of 60 d with mepartricin (40 mg 4 times per day) compared with placebo. Hormonal first-line treatment cannot be recommended according to published data in patients with CP/CPPS.

Only two RCTs studying the potential role of phytotherapeutic agents were eligible for inclusion. A small trial by Shoskes et al tested the clinical efficiency of quercetin, a bioflavonoid with antioxidative properties [32] . Quercetin (500 mg 2 times per day) over 4 wk provided significant symptomatic amelioration compared with placebo as determined by the NIH-CPSI. Another clinical trial analyzed the therapeutic benefit of cernilton, a standardized pollen extract [33] . A 12-week course of cernilton (two capsules every 8 h) led to a significant improvement of the NIH-CPSI score compared with placebo. Therefore, clinical evidence qualifies certain phytotherapeutic agents as a treatment modality. With only very few side effects, they can be recommended as primary therapy or a combination in multimodal treatment regimens.

Because pain is the dominant symptom in CP/CPPS, analgesic neuromodulatory agents appear to be a promising approach. Only one RCT investigated the benefit of an oral course of pregabalin in increasing dosages (from 150 mg to 600 mg daily) over 6 wk [34] . An adequate treatment response was confirmed by NIH-CPSI for the pain subdomain, but at the same time neurologic side effects were more frequent in the pregabalin group. This therapeutic regimen failed to demonstrate a significant clinical benefit over placebo based on an analysis of the primary end point, although important secondary outcomes were positive [35] . Thus published data do not recommend pregabalin as a first-line single treatment of CP/CPPS.

On the assumption of a common pathophysiologic origin of conditions causing pelvic pain syndromes like interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome (IC/BPS) and CP/CPPS, one RCT evaluated the effect of pentosan polysulfate (300 mg 3 times per day), a medication indicated for IC/BPS, over 16 wk compared with placebo in patients diagnosed with CP/CPPS [36] . This trial observed a positive treatment response in the treatment arm with regard to NIH-CPSI domains, but it did not reach statistical significance compared with the placebo group. According to clinical evidence, pentosan polysulfate cannot be recommended as a first-line treatment of patients with CP/CPPS.

Physiotherapeutic approaches have been shown to provide moderate clinical relief in pain syndromes associated with skeletal muscle dysfunction. With regard to CP/CPPS, various modalities like myofascial physical therapy [37] , percutaneous posterior tibial nerve stimulation (PTNS) [38] , acupuncture or electroacupuncture [39] and [40], perineal extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT) [41] , sono-electro-magnetic therapy (SEMT) [42] , or aerobic exercise [43] have been evaluated in randomized sham-controlled trials. A randomized feasibility trial of myofascial physical therapy by Fitzgerald et al included both patients diagnosed with IC/BPS and CP/CPPS [37] . Myofascial physical therapy displayed a relevant mean decrease of 14.4 points in the NIH-CPSI total score after 10 wk of direct physiotherapy. Compared with an unspecific global therapeutic massage (sham group), this change did not reach statistical significance.

Trials evaluating the clinical benefit of perineal ESWT and PTNS in patients diagnosed with CP/CPPS type IIIB indicated a statistically relevant improvement measured by the NIH-CPSI total score. SEMT showed no significant difference in the NIH-CPSI total score after 16 wk compared with the placebo procedure, but it revealed a therapeutic benefit for the quality-of-life subscore as a secondary outcome.

Acupuncture proved to be efficient after 10 wk of treatment versus the sham group, but this first improvement appeared not to be durable in the course of follow-up. Electroacupuncture suggested a statistically significant benefit in the pain subdomain compared with the control group. However, no relevant change was observed for the total NIH-CPSI score.

Another trial investigated the influence of a course of 18 wk of physical training on the clinical outcome of a patient diagnosed with CP/CPPS. A specific aerobic exercise and an unspecific stretching and motion exercise (sham control) were established and evaluated. Aerobic exercise turned out to be superior to the control group as measured by a validated Italian version of the NIH-CPSI questionnaire. Pain in particular was significantly improved in the group performing aerobic exercise. The heterogeneity of clinical data available and methodologic difficulties in conducting RCTs for this kind of treatment modality do not allow to give a recommendation for specific physiotherapeutic options as a primary intervention. More sham-controlled studies are needed. Nevertheless, published results suggest that at least subgroups of patients diagnosed with CP/CPPS may profit from physical therapy.

The previous discussion revealed quite impressively our dilemma with randomized controlled studies evaluating the effectiveness of monotherapies we considered to be helpful. Clinical trials of good quality but apparently underpowered reported the traditional first-line treatments as failures. Interestingly, randomized controlled studies investigating uncommon approaches like phytotherapies confirmed significant clinical efficacy. Only a few trials addressed the impact of combination therapies. The trial by Alexander et al investigated the influence of a monotherapy with ciprofloxacin (500 mg 2 times per day) or tamsulosin (0.4 mg 4 times per day) or a combination of ciprofloxacin and tamsulosin versus placebo [15] . After a treatment course of 6 wk, neither the monotherapies nor the combination were superior to placebo.

The placebo-controlled trial by Tugcu et al randomized 90 patients diagnosed with CP/CPPS category IIIB to receive doxazosin (4 mg 4 times per day), a triple therapy consisting of doxazosin (4 mg 4 times per day), the anti-inflammatory ibuprofen (400 mg 4 times per day), and the muscle relaxant thiocolchicoside (12 mg four times per day), or a placebo once per day [23] . After a therapy course of 6 mo, the single treatment with doxazosin was equally effective as the triple therapy. Both treatment arms were significantly superior to the placebo group, and clinical outcome was stable after an additional 6 mo of follow-up.

Throughout this review readers might wonder why well-conducted clinical trials evaluating the same therapeutic options result in this heterogeneity of clinical outcomes. How can a general recommendation be formulated for the successful management of CP/CPPS? Published data of randomized placebo/sham-controlled trials were pooled and subjected to meta-analysis [6] and [7]. No recommendations for monotherapies can be made based on these results. Data suggest that the combination of α-blockers and antibiotics may have a decent therapeutic effect with regard to symptom scores for selected patients [6] . However, certain limitations have to be taken into account when data synthesis in the form of a meta-analysis is performed. Some studies represent small single-center trials with inadequate control groups and blinding. According to basic characteristics, duration of disease and prior treatments are not documented. This makes the interpretation of this heterogeneous pool of data difficult and needs to be considered when recommendations are formulated.

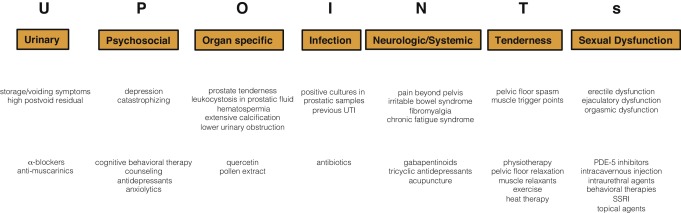

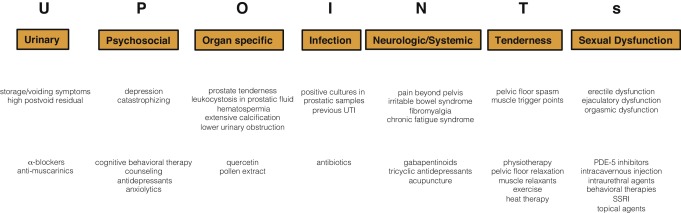

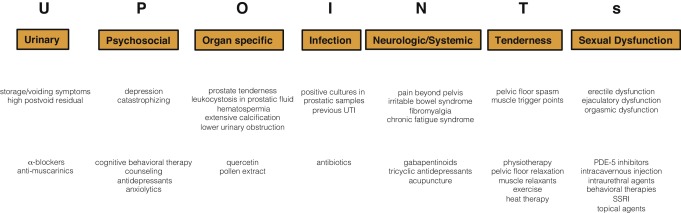

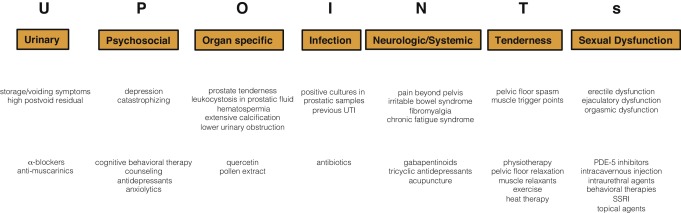

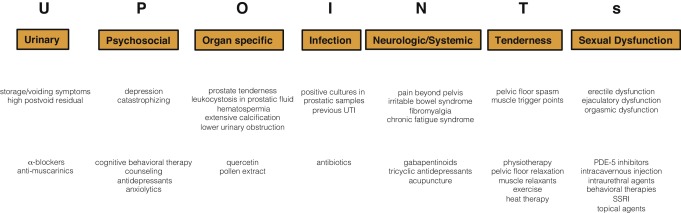

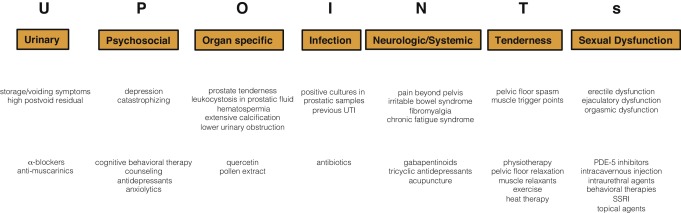

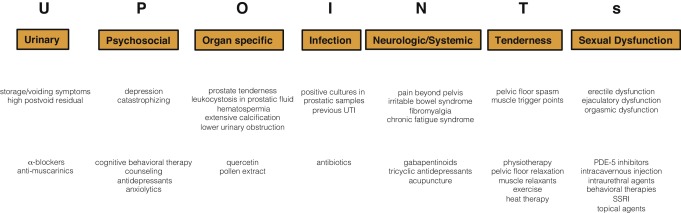

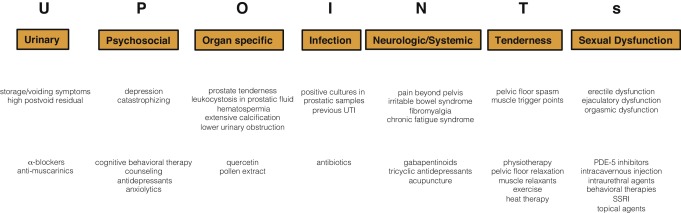

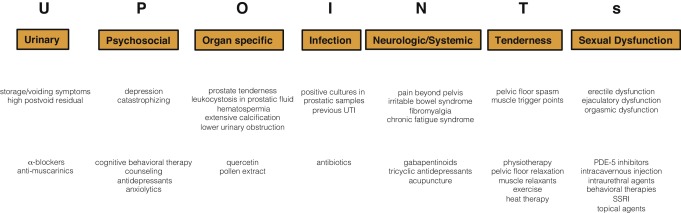

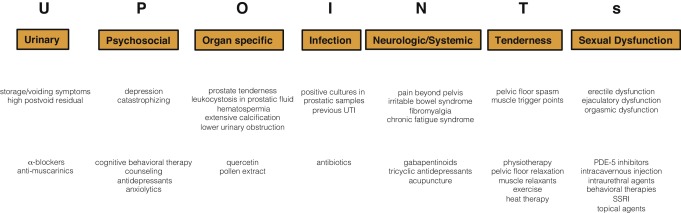

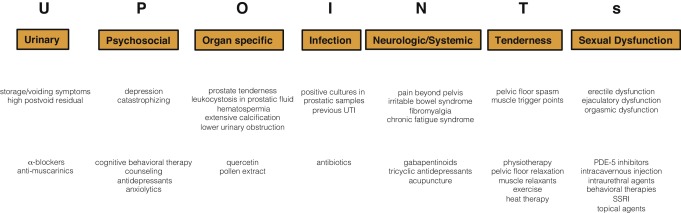

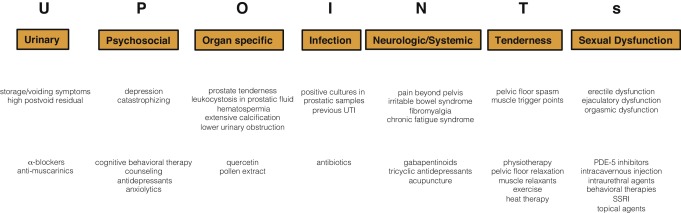

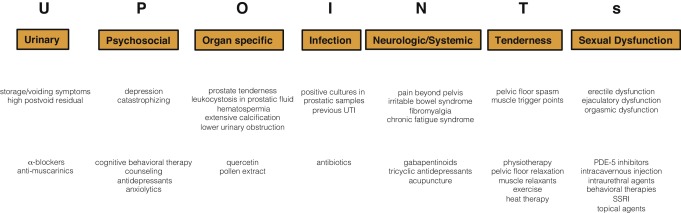

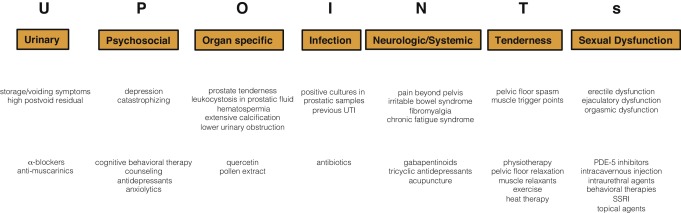

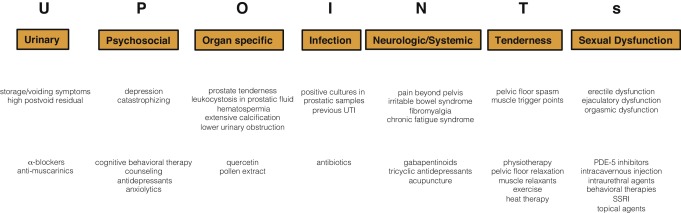

UPOINT represents a novel 6-point clinical phenotyping system for the management of CP/CPPS. It profiles patients and indicates individual treatment targets to implement an individualized multimodal therapeutic regimen. The six UPOINT domains comprise Urinary symptoms, Psychological dysfunction, Organ-specific symptoms, Infection, Neurologic/systemic conditions, and Tenderness of muscles ( Fig. 3 ) [44], [45], [46], and [47]. UPOINT is able to discriminate clinical phenotypes, and positive domains appear to correlate with symptom severity and duration of disease [45] . Clinical results indicate a correlation between the number of positive UPOINT domains and total NIH-CPSI score [48] and [49]. With sexual dysfunction as a common condition affecting 40–70% of men with CP/CPPS [50], [51], [52], [53], and [54], the inclusion of an additional domain for Sexual dysfunction was proposed and evaluated. The modified UPOINTs algorithm has been suggested to support an optimized stratification of individual phenotypic profiles. However, clinical studies attempting to confirm an improved correlation between positive UPOINTs domains and symptom severity revealed heterogeneous results [48], [55], [56], and [57].

Most clinical trials conducted so far speak in favor of the extended UPOINTs approach. First studies suggest that the multimodal treatment guided by UPOINT leads to a significant improvement of symptoms and quality of life [58] . In a prospective study including a cohort of 100 men positive for a minimum of three UPOINT domains, clinical response to a phenotypically directed multimodal treatment was evaluated by a change in NIH-CPSI score. Almost 84% of patients met the primary end point of at least a 6-point change in total NIH-CPSI score with a median follow-up of 50 wk. All NIH-CPSI subdomains comprising scores for pain, urinary symptoms, and quality of life were significantly improved (each p ˂ 0.0001). Although first results are promising, further clinical RCTs are warranted for a complete validation of the UPOINTs approach. Categorization and treatment options directed by UPOINTs phenotype are depicted in Figure 3 .

In this section we introduce three index patients diagnosed with CP/CPPS. This selection may represent the most frequent clinical presentations in daily routine. Applying the UPOINTs algorithm, we have formulated our best practice recommendations based on published data in concert with expert opinion.

A 42-year-old man presents with modest perineal discomfort radiating to both testicles. He complains about hesitancy and a slow stream. In the last 2 yr he had two episodes of an acute bacterial prostatitis that were treated with an antimicrobial for 2 wk each time. The patient explains that sometimes his symptoms flare up and resolve partially on antibiotics. On digital rectal examination (DRE), the prostate feels slightly enlarged, and the patient reports moderate tenderness to palpation. Laboratory testing including PSA and C-reactive protein (CRP) was normal. A two-glass test is performed, and no pathogen is detected. Post–prostatic massage urine is positive for leukocytes, and microscopy shows an inflammatory pattern. Prostate volume as determined by transrectal ultrasonography is about 30 ml. Peak urinary flow rate is 14 ml/s with a voided urine volume of 300 ml. Postvoid residual urine volume is 80 ml. The patient is on no regular medication.

Table 3 shows the phenotypic evaluation according to UPOINTs and the resulting treatment plan.

Table 3 Phenotypic evaluation and recommendations on treatment

| Diagnosis | CP/CPPS category IIIA |

|---|---|

| UPOINTs | |

| U | Hesitancy, weak stream |

| P | NA |

| O | Tenderness to palpation, flares |

| I | NA |

| N | NA |

| T | NA |

| s | NA |

| Treatment | |

| U | α-Blockers |

| O | Pollen extract and/or quercetin, NSAID for flares |

CP/CPPS = chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome; NA = not applicable; NSAID = nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

A 46-year-old man presents with modest perineal discomfort. The patient complains about hesitancy and a slow stream, which has been increasing in recent years along with an increase in perineal pain. He wakes up at least three times a night to urinate. He is sexually active and describes post-ejaculatory pain. On DRE the prostate feels normal, but the patient reports moderate tenderness to palpation. Laboratory testing including PSA and CRP is normal. A two-glass test is performed, but no signs of inflammation or bacterial infection are detected. Prostate volume as determined by transrectal ultrasonography is about 30 ml. Peak urinary flow rate is 12 ml/s with a voided urine volume of 250 ml. Postvoid residual urine volume is 120 ml. The patient is on no regular medication.

Table 4 shows the phenotypic evaluation according to UPOINTs and the resulting treatment plan.

Table 4 Phenotypic evaluation and recommendations on treatment

| Diagnosis | CP/CPPS category IIIB |

|---|---|

| UPOINTs | |

| U | Hesitancy, weak stream |

| P | NA |

| O | Tenderness to palpation, perineal discomfort |

| I | NA |

| N | NA |

| T | Perineal and pelvic muscle tenderness |

| s | NA |

| Treatment | |

| U | α-Blockers |

| O | Pollen extract and/or quercetin |

| T | Local heat therapy (cushion, pads), physiotherapy/pelvic floor relaxation |

CP/CPPS = chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome; NA = not applicable.

A 42-year-old man presents with modest perineal discomfort. Burning sensations are radiating to the abdomen and his back. The patient is anxious about his symptoms and fears a malignant process. His worries and doubts have been progressing in recent years. It started with his diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome. The development of chronic fatigue syndrome and intermediate episodes of migraine headaches are secondary findings that emerged in the last 3 yr. The patient admits that depressive episodes have become more frequent since the perineal pain started. On DRE the prostate feels normal. The pelvic floor is tender to touch. Laboratory testing including PSA and CRP is normal. A two-glass test is performed, but no signs of inflammation or bacterial infection are detected. The patient is on no regular medication.

Table 5 shows the phenotypic evaluation according to UPOINTs and the resulting treatment plan.

Table 5 Phenotypic evaluation and recommendations on treatment

| Diagnosis | CP/CPPS category III B |

|---|---|

| UPOINTs | |

| U | NA |

| P | Depression, catastrophizing |

| O | NA |

| I | NA |

| N | Neuropathic pain |

| T | Perineal and pelvic muscle tenderness |

| s | NA |

| Treatment | |

| P | Psychological support, referral to psychologist (cognitive behavioral therapy), tricyclic antidepressants |

| N | Pregabalin, tricyclic antidepressants, acupuncture |

| T | Physiotherapy/pelvic floor relaxation, muscle relaxants |

CP/CPPS = chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome; NA = not applicable.

In this comprehensive review we presented our current understanding of best practice management of symptomatic CP/CPPS based on published data in concert with expert opinion. We have not been able to decipher the pathophysiology underlying CP/CPPS to identify common key targets for treatment. This has made the management of this bothersome condition very challenging for both clinicians and patients. Our inability to formulate recommendations with a high grade of evidence for efficient monotherapies reflects the main problem. Scientific reports do not speak in favor of a common etiology applying to all forms of CP/CPPS. A multifactorial genesis appears to contribute to an individual multifaceted complex of symptoms for every patient diagnosed with CP/CPPS. The current understanding of the management of CP/CPPS strongly suggests a multimodal therapeutic approach addressing the individual clinical phenotypic profile. More RCTs are warranted for validation of this phenotype-directed treatment. Although its role for the management of CP/CPPS has still to be defined, it appears to be a promising and effective alternative to the current empirical sequential monotherapy.

Author contributions: Giuseppe Magistro had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Magistro, Nickel.

Acquisition of data: Magistro, Wagenlehner, Nickel.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Magistro, Wagenlehner, Grabe, Weidner, Stief, Nickel.

Drafting of the manuscript: Magistro, Wagenlehner, Grabe, Weidner, Stief, Nickel.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Magistro, Wagenlehner, Grabe, Weidner, Stief, Nickel.

Statistical analysis: None.

Obtaining funding: None.

Administrative, technical, or material support: None.

Supervision: Magistro, Wagenlehner, Nickel.

Other (specify): None.

Financial disclosures: Giuseppe Magistro certifies that all conflicts of interest, including specific financial interests and relationships and affiliations relevant to the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript (eg, employment/affiliation, grants or funding, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, royalties, or patents filed, received or pending), are the following: J. Curtis Nickel is a consultant/researcher for Pfizer, Astellas, Ferring, Farr Laboratories, Taris, Allergan, Aquinox, Lilly, NIH/NIDDK, and CIHR. Florian M.E. Wagenlehner is a consultant/researcher for Astellas, Astra-Zeneca, Bionorica, Calixa, Cerexa, Cernelle, Cubist, Galenus, Leo-Pharma, Merlion, OM-Pharma, Pierre Fabre, Rosen Pharma, and Zambon. The other authors having nothing to disclose.

Funding/Support and role of the sponsor: None.

Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) and pelvic pain due to pathologies of the prostate have always considerably affected quality of life of men of all ages. Epidemiologic data suggest that the prevalence of prostatitis-like symptoms is comparable with ischemic heart disease and diabetes mellitus. The rate of prostatitis-like symptoms ranges from 2.2% to 9.7%, with a mean prevalence of 8.2% [1] .

In the late 1990s, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) established a consensus definition and classification system for prostatitis [2] . It has been accepted internationally in both clinical practice and research ( Table 1 ). Prostatitis syndromes comprise infectious forms (acute and chronic), the chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CPPS), and asymptomatic prostatitis [2] . In <10% of patients with prostatitis syndrome, a causative uropathogenic organism can be detected. An acute bacterial episode will lead to chronic bacterial prostatitis in 10% and to CPPS in a further 10% [3] . CPPS accounts for most of the prostatitis-like symptoms in >90% of men.

Table 1 National Institutes of Health classification system for prostatitis syndromes

| Category | Nomenclature |

|---|---|

| I | Acute bacterial prostatitis |

| II | Chronic bacterial prostatitis |

| III | Chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome |

| IIIA | Inflammatory |

| IIIB | Noninflammatory |

| IV | Asymptomatic prostatitis |

The National Institutes of Health Chronic Prostatitis Symptom Index (NIH-CPSI) presents an objective assessment tool and outcome measure for prostatitis-like symptoms [4] and [5]. The introduction of a generally accepted classification system and an objective outcome measure led to a plethora of clinical trials that made one particular point clear. Although the treatment of bacterial prostatitis obviously relies on the adequate use of antimicrobial agents, successful management of CPPS has always been a formidable task. The complex and heterogeneous pathophysiology of CPPS is poorly understood. Consequently, an effective monotherapy is not available, which makes the management of CPPS challenging for both physicians and patients. Clinical trials were not able to identify a monotherapy with significant clinical efficacy. A meta-analysis evaluating data of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) using the NIH-CPSI as a common outcome measure failed to derive a guideline statement on the treatment of this bothersome condition [6] and [7].

The dilemma of limited success of clinical trials prompted us to provide a comprehensive review with expert interpretations of the available literature to formulate best practice recommendations. Introducing index patients diagnosed with CPPS, we demonstrate how these recommendations might be applied in clinical practice. The main objective of this review is to present best practice recommendations for the management of CPPS (NIH type III).

We performed a systematic review of the literature in the PubMed and Cochrane database according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis statement [8] . We searched for RCTs and meta-analyses on the treatment of chronic prostatitis CP/CPPS from January 1988 to December 2014. A detailed description of the search strategy is presented in Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Figure 1. In addition, references of review articles were screened for possibly missed articles.

RCTs published in English were selected if they met the following criteria: (1) RCTs (comparisons; placebo or sham controlled; no invasive procedures), (2) patients were classified as CP category IIIA or IIIB according to the NIH consensus definition, (3) at least 10 individuals were evaluated per treatment arm, and (4) the NIH-CPSI score was utilized as an outcome measure for CP/CPPS. Articles were first reviewed independently by two authors to determine their eligibility for inclusion. With consensus the article moved on to the next round, and if the first two reviewers disagreed, a third reviewer was included to reach unanimous agreement ( Fig. 1 ).

The systematic literature review revealed 28 RCTs for the therapy of CPPS eligible for inclusion. Two performed meta-analyses published in the last 4 yr on this subject [6] and [7] were not able to provide any relevant useful information for clinical practice. We realized that no significant clinical data from recently published RCTs could be included since the last meta-analyses were performed (Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Fig. 1). Another attempt to evaluate the available clinical data would add nothing to the literature and not provide any more guidance to practicing urologists. Consequently, we present the available literature on treatment modalities to outline the scientific dilemma and formulate best practice statements that used published data in concert with expert opinion. This does not use formal meta-analysis. We attempted to outline the complete management of CPPS including diagnostic assessment and treatment.

The introduction of index patients demonstrates how to implement the presented recommendations in clinical practice. After the conception of each index patient, the relevant symptoms were identified and treatment options were discussed. For this purpose, every author received the different case presentations and independently analyzed symptoms, treatment targets, and therapeutic options. The results were returned to G.M., who collected responses and pointed out discrepancies. After discussions we agreed on the points presented in tables.

CP/CPPS (NIH category III) is defined as urologic pain or discomfort in the pelvic region, associated with urinary symptoms and/or sexual dysfunction, lasting for at least 3 of the previous 6 mo. Differential diagnoses of pelvic pain such as urinary tract infection, cancer, anatomic abnormalities, or neurologic disorders need to be excluded. CP/CPPS is subclassified as an inflammatory type (NIH category IIIA) and a noninflammatory type (NIH category IIIB) according to the presence of leukocytes in prostatic samples [2] .

Patients with prostatitis-like symptoms report perineal, testicular, and penile discomfort. Pain may also be accompanied by LUTS and sexual dysfunction. Symptoms persist for at least 3 mo. CP/CPPS is often associated with negative cognitive, behavioral, sexual, or emotional consequences that should be addressed as part of the medical history. The correct classification demands a systematic diagnostic assessment.

The first step is to assess the severity and impact of symptoms by utilizing the NIH-CPSI (level of evidence 2b; grade of recommendation B) [9] . The NIH-CPSI presents an objective assessment tool and outcome measure for prostatitis-like symptoms [4] and [5]. The symptom-scoring questionnaire is a reliable tool for basic evaluation and therapeutic monitoring. This self-administered questionnaire asks nine questions that are scored in three domains: pain, urinary symptoms, and the impact on quality of life. Severity categories have been proposed, and a 6-point decline from the baseline total score is considered the threshold for a positive therapeutic response. In addition, the International Prostate Symptom Score [10] and the International Index of Erectile Function [11] present optional valuable outcome measures to evaluate the current condition and course of disease in response to treatment.

Physical examination of the abdomen, genitalia, perineum, and prostate is mandatory. Additional evaluation of myofascial trigger points and/or musculoskeletal dysfunction of the pelvis and pelvic floor may be helpful.

Microbiologic localization cultures are the standard laboratory method for identifying chronic bacterial prostatitis (NIH type II). The four-glass test according to Meares and Stamey is recommended [12] . First voided urine, midstream urine, expressed prostatic secretion, and post–prostate massage urine are analyzed for identification and quantification of pathogens and inflammation. A simpler two-glass test is also possible as a reasonably accurate screen for initial evaluation. It involves the investigation of pre– and post–prostate massage urine. It was shown to correlate well with the four-glass test [13] . The four-glass test or two-glass test are used to exclude bacterial infection. Although the detection of leukocytes confirms CP/CPPS type IIIA, in type IIIB no signs of inflammation are observed. The clinical value of this categorization has never been validated. Semen cultures of the ejaculate alone are not sufficient for diagnosis.

Laboratory testing including complete blood count, inflammatory parameters, and serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) is not recommended to diagnose CP/CPPS. PSA may be considered if patients are at risk for prostate cancer. Transrectal ultrasound is not useful for the diagnosis, unless there is a specific indication in selected patients such as intraprostatic abscess, calcification, or dilatation of seminal vesicles.

Urodynamic studies may be considered in selected patients with voiding/storage symptoms suggestive of bothersome LUTS. Cystoscopy or retrograde urethrography may be considered to rule out bladder outlet obstruction. Figure 2 shows a diagnostic algorithm for patients with prostatitis-like symptoms [9] and [14].

Due to the heterogeneity and the still elusive pathophysiology of CP/CPPS, the establishment of effective treatment modalities remains challenging. A multitude of clinical trials failed to identify an efficient primary treatment. Here we present published randomized placebo- or sham-controlled clinical trials using the NIH-CPSI as an objective outcome measure ( Table 2 ).

Table 2 Included randomized clinical trials for treatment of chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome

| Treatment | Duration | Patients, n | Basic mean NIH-CPSI total score | Mean change | Significance | Jadad total score | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibiotics | |||||||

| Ciprofloxacin vs tamsulosin vs combination vs placebo |

6 wk | 49 49 49 49 |

24.2 24.6 25.3 25.0 |

−6.2 −4.4 −4.1 −.4 |

No (p > 0.05) |

≥3 | [15] |

| Levofloxacin vs placebo |

6 wk | 45 35 |

24.4 21.3 |

−5.6 −3.1 |

No (p > 0.05) |

≥3 | [16] |

| Tetracycline vs placebo |

12 wk | 24 24 |

35.6 NR |

−8.5 NR |

Yes (p < 0.01) |

<3 | [17] |

| α-Blockers | |||||||

| Tamsulosin vs placebo |

6 wk | 27 30 |

26.4 26.2 |

−9.1 −5.5 |

Yes (p < 0.05) |

≥3 | [19] |

| Alfuzosin vs placebo |

12 wk | 138 134 |

23.8 25.1 |

−7.1 −6.5 |

No (p > 0.05) |

≥3 | [20] |

| Silodosin 8 mg vs silodosin 4 mg vs placebo |

12 wk | 45 52 54 |

26.8 26.0 27.9 |

−10.2 −12.1 −8.5 |

Yes (p < 0.05) |

≥3 | [18] |

| Doxazosin vs DIT vs placebo |

24 wk | 30 30 30 |

23.1 21.9 22.9 |

−10.6 −10.2 −0.7 |

Yes (p < 0.001) |

<3 | [23] |

| Terazosin vs placebo |

14 wk | 43 43 |

25.1 27.2 |

−14.3 −10.2 |

Yes (p = 0.01) |

<3 | [22] |

| Alfuzosin vs placebo |

24 wk | 17 20 |

26.0 23.0 |

−9.9 −3.8 |

Yes (p = 0.01) |

<3 | [21] |

| Anti-inflammatories | |||||||

| Rofecoxib 25 mg vs rofecoxib 50 mg vs placebo |

6 wk | 53 49 59 |

22.5 20.5 22.9 |

−4.9 −6.2 −4.2 |

No (p > 0.05) |

≥3 | [24] |

| Prednisolone vs placebo |

4 wk | 9 12 |

25.5 23.4 |

NR | No (p > 0.05) |

≥3 | [26] |

| Celecoxib vs placebo |

6 wk | 32 32 |

23.9 24.3 |

−8.0 −4.8 |

Yes (p < 0.015) |

≥3 | [27] |

| Tanezumab vs placebo |

Single dose | 30 32 |

25.0 26.0 |

−4.3 −2.8 |

No (p > 0.05) |

<3 | [25] |

| Zafirlukast vs placebo |

4 wk | 10 7 |

22.4 23.4 |

−4.6 −8.1 |

No (p > 0.05) |

≥3 | [28] |

| OM-89 vs placebo |

12 mo | 94 91 |

21.8 23.0 |

−10.4 −9.8 |

No (p > 0.05) |

≥3 | [29] |

| Hormonal agents | |||||||

| Finasteride vs placebo |

24 wk | 33 31 |

20.1 22.5 |

−3.0 −0.8 |

No (p > 0.05) |

≥3 | [30] |

| Mepartricin vs placebo |

60 d | 13 13 |

25.0 25.0 |

−15.0 −5.0 |

Yes (p < 0.01) |

≥3 | [31] |

| Phytotherapy | |||||||

| Cernilton vs placebo |

12 wk | 70 69 |

19.3 20.3 |

−7.7 −5.2 |

Yes (p < 0.05) |

≥3 | [33] |

| Quercetin vs placebo |

4 wk | 15 13 |

21.0 20.2 |

−7.9 −1.4 |

Yes (p < 0.01) |

≥3 | [32] |

| Neuromodulation | |||||||

| Pregabalin vs placebo |

6 wk | 218 106 |

26.2 25.9 |

−6.5 −4.3 |

No (p > 0.05) |

≥3 | [34] |

| Modulation of bladder physiology | |||||||

| Pentosan polysulfate vs placebo |

16 wk | 51 49 |

27.1 25.8 |

−5.9 −3.2 |

No (p > 0.05) |

≥3 | [36] |

| Physical therapy | |||||||

| GTM vs MPT |

10 wk | 11 12 |

25.8 33.5 |

−6.8 −14.4 |

No (p > 0.05) |

≥3 | [37] |

| PTNS vs sham |

12 wk | 45 44 |

23.6 22.8 |

−13.4 −1.4 |

Yes (p < 0.001) |

<3 | [38] |

| Acupuncture vs sham |

10 wk | 44 45 |

24.8 25.2 |

−10.3 −6.2 |

Yes (p < 0.05) |

≥3 | [39] |

| Electroacupuncture vs sham vs control |

6 wk | 12 12 12 |

26.9 25.5 28.0 |

−9.5 −3.5 −3.5 |

Yes (p < 0.001) |

≥3 | [40] |

| ESWT vs sham |

4 wk | 30 30 |

23.2 25.1 |

−3.5 −0.1 |

Yes (p < 0.05) |

≥3 | [41] |

| Aerobic exercise vs sham |

18 wk | 52 51 |

21.9 23.0 |

−7.4 −4.8 |

Yes (p < 0.05) |

<3 | [43] |

| SEMT vs sham |

16 wk | 30 30 |

25.8 25.2 |

−7.2 −4.6 |

No (p > 0.05) |

≥3 | [42] |

DIT = doxazosin plus ibuprofen plus thiocolchicoside; ESWT = extracorporeal shock wave therapy; GTM = global therapeutic massage; MPT = myofascial physical therapy; NIH-CPSI = National Institutes of Health Chronic Prostatitis Symptom Index; PTNS = posterior tibial nerve stimulation; SEMT = sono-electro-magnetic therapy.

Antibiotics have been proposed as an option for the treatment of CP/CPPS. But recommendations were based on empirical experience rather than evidence-based studies. Three RCTs were eligible for inclusion. Six-week courses of therapy with ciprofloxacin (500 mg 2 times per day) [15] or levofloxacin (500 mg 4 times per day) [16] did not result in a statistically significant treatment response measured by the NIH-CPSI compared with placebo. Both studies were of good quality but apparently underpowered. The clinical trial by Zhou et al compared the efficiency of a treatment with tetracycline (500 mg 2 times per day) over 12 wk versus placebo [17] . Despite some quality issues, the authors report a significant mean decrease of 18.5 points in the NIH-CPSI after treatment. Altogether the available RCTs failed to support the recommendation to use antimicrobial agents as a primary treatment option.

Seven RCTs investigating the benefit of a monotherapy with α-adrenergic receptor blockers versus placebo met the criteria for inclusion [15], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], and [23]. The outcomes regarding clinical efficiency determined by NIH-CPSI were quite heterogeneous. Smaller trials evaluating a course of at least 12 wk with different α-blockers provided evidence for positive clinical response [18], [21], [22], and [23], whereas most studies analyzing a shorter duration of 6 wk did not confirm a therapeutic benefit. Of note, clinical trials testing the α-blocker tamsulosin versus placebo over 6 wk in a comparable study population with similar baseline characteristics revealed different clinical outcomes. On the one hand, the study by Alexander et al [15] failed to prove clinical efficiency; on the other hand, the trial by Nickel and colleagues supported the use of tamsulosin [19] . Due to the heterogeneity of published data, α-blockers cannot be recommended as first-line monotherapy. However, a prolonged treatment of 12 wk in patients with bothersome LUTS and no prior treatment with α-blockers may be considered in a multimodal therapeutic regimen.

A role of inflammation and immune dysfunction has been proposed for the pathophysiology of CPPS and appears to be evident for CP/CPPS NIH category IIIA. Five RCTs have been included that evaluated the therapeutic effect of anti-inflammatory agents [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], and [29]. Various approaches have been subjected to clinical trials. Interestingly, only two studies exclusively analyzed category type IIIA. Among the two trials investigating the cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors rofecoxib (25 mg or 50 mg 4 times per day) [24] and celecoxib (200 mg 4 times per day) [27] over 6 wk compared with placebo, only the study by Zhao et al was able to reveal clinical efficiency of celecoxib in patients diagnosed with CPPS type IIIA. But this treatment response was limited to the duration of therapy. Two weeks after treatment, no clinical improvement was observed.

A reducing course of oral prednisolone over 4 wk failed to demonstrate therapeutic efficiency [26] . Neither tanezumab [25] , a humanized monoclonal antibody directed against nerve growth factor, nor zafirlukast [28] , a leukotriene antagonist, were able to demonstrate superiority over placebo. In addition, OM-89, a modified preparation of lysed pathogenic Escherichia coli, was evaluated as an immunostimulating agent for the treatment of patients with CP/CPPS [29] . Again, no statistically significant difference was observed between treatment arm and placebo group with regard to clinical efficacy. To conclude, clinical trials strongly suggest that a monotherapy with anti-inflammatory or immunomodulating agents is not effective.

Two RCTs investigating the impact of hormonal modulation on prostatitis-like symptoms in patients diagnosed with CP/CPPS were selected for inclusion. The clinical trial by Nickel et al evaluated the efficiency of the specific type II 5α-reductase inhibitor finasteride versus placebo in patients with CP/CPPS category IIIA [30] . It represents a standard treatment for LUTS in patients with BPH, but finasteride (5 mg 4 times per day) over 6 mo was not able to significantly improve the clinical outcome in this study population. Another clinical trial by De Rose et al investigated the role of mepartricin, a compound known to decrease estrogen levels in the prostate [31] . This small trial reported a significant clinical improvement measured by the NIH-CPSI after a course of 60 d with mepartricin (40 mg 4 times per day) compared with placebo. Hormonal first-line treatment cannot be recommended according to published data in patients with CP/CPPS.

Only two RCTs studying the potential role of phytotherapeutic agents were eligible for inclusion. A small trial by Shoskes et al tested the clinical efficiency of quercetin, a bioflavonoid with antioxidative properties [32] . Quercetin (500 mg 2 times per day) over 4 wk provided significant symptomatic amelioration compared with placebo as determined by the NIH-CPSI. Another clinical trial analyzed the therapeutic benefit of cernilton, a standardized pollen extract [33] . A 12-week course of cernilton (two capsules every 8 h) led to a significant improvement of the NIH-CPSI score compared with placebo. Therefore, clinical evidence qualifies certain phytotherapeutic agents as a treatment modality. With only very few side effects, they can be recommended as primary therapy or a combination in multimodal treatment regimens.

Because pain is the dominant symptom in CP/CPPS, analgesic neuromodulatory agents appear to be a promising approach. Only one RCT investigated the benefit of an oral course of pregabalin in increasing dosages (from 150 mg to 600 mg daily) over 6 wk [34] . An adequate treatment response was confirmed by NIH-CPSI for the pain subdomain, but at the same time neurologic side effects were more frequent in the pregabalin group. This therapeutic regimen failed to demonstrate a significant clinical benefit over placebo based on an analysis of the primary end point, although important secondary outcomes were positive [35] . Thus published data do not recommend pregabalin as a first-line single treatment of CP/CPPS.

On the assumption of a common pathophysiologic origin of conditions causing pelvic pain syndromes like interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome (IC/BPS) and CP/CPPS, one RCT evaluated the effect of pentosan polysulfate (300 mg 3 times per day), a medication indicated for IC/BPS, over 16 wk compared with placebo in patients diagnosed with CP/CPPS [36] . This trial observed a positive treatment response in the treatment arm with regard to NIH-CPSI domains, but it did not reach statistical significance compared with the placebo group. According to clinical evidence, pentosan polysulfate cannot be recommended as a first-line treatment of patients with CP/CPPS.

Physiotherapeutic approaches have been shown to provide moderate clinical relief in pain syndromes associated with skeletal muscle dysfunction. With regard to CP/CPPS, various modalities like myofascial physical therapy [37] , percutaneous posterior tibial nerve stimulation (PTNS) [38] , acupuncture or electroacupuncture [39] and [40], perineal extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT) [41] , sono-electro-magnetic therapy (SEMT) [42] , or aerobic exercise [43] have been evaluated in randomized sham-controlled trials. A randomized feasibility trial of myofascial physical therapy by Fitzgerald et al included both patients diagnosed with IC/BPS and CP/CPPS [37] . Myofascial physical therapy displayed a relevant mean decrease of 14.4 points in the NIH-CPSI total score after 10 wk of direct physiotherapy. Compared with an unspecific global therapeutic massage (sham group), this change did not reach statistical significance.

Trials evaluating the clinical benefit of perineal ESWT and PTNS in patients diagnosed with CP/CPPS type IIIB indicated a statistically relevant improvement measured by the NIH-CPSI total score. SEMT showed no significant difference in the NIH-CPSI total score after 16 wk compared with the placebo procedure, but it revealed a therapeutic benefit for the quality-of-life subscore as a secondary outcome.

Acupuncture proved to be efficient after 10 wk of treatment versus the sham group, but this first improvement appeared not to be durable in the course of follow-up. Electroacupuncture suggested a statistically significant benefit in the pain subdomain compared with the control group. However, no relevant change was observed for the total NIH-CPSI score.

Another trial investigated the influence of a course of 18 wk of physical training on the clinical outcome of a patient diagnosed with CP/CPPS. A specific aerobic exercise and an unspecific stretching and motion exercise (sham control) were established and evaluated. Aerobic exercise turned out to be superior to the control group as measured by a validated Italian version of the NIH-CPSI questionnaire. Pain in particular was significantly improved in the group performing aerobic exercise. The heterogeneity of clinical data available and methodologic difficulties in conducting RCTs for this kind of treatment modality do not allow to give a recommendation for specific physiotherapeutic options as a primary intervention. More sham-controlled studies are needed. Nevertheless, published results suggest that at least subgroups of patients diagnosed with CP/CPPS may profit from physical therapy.

The previous discussion revealed quite impressively our dilemma with randomized controlled studies evaluating the effectiveness of monotherapies we considered to be helpful. Clinical trials of good quality but apparently underpowered reported the traditional first-line treatments as failures. Interestingly, randomized controlled studies investigating uncommon approaches like phytotherapies confirmed significant clinical efficacy. Only a few trials addressed the impact of combination therapies. The trial by Alexander et al investigated the influence of a monotherapy with ciprofloxacin (500 mg 2 times per day) or tamsulosin (0.4 mg 4 times per day) or a combination of ciprofloxacin and tamsulosin versus placebo [15] . After a treatment course of 6 wk, neither the monotherapies nor the combination were superior to placebo.

The placebo-controlled trial by Tugcu et al randomized 90 patients diagnosed with CP/CPPS category IIIB to receive doxazosin (4 mg 4 times per day), a triple therapy consisting of doxazosin (4 mg 4 times per day), the anti-inflammatory ibuprofen (400 mg 4 times per day), and the muscle relaxant thiocolchicoside (12 mg four times per day), or a placebo once per day [23] . After a therapy course of 6 mo, the single treatment with doxazosin was equally effective as the triple therapy. Both treatment arms were significantly superior to the placebo group, and clinical outcome was stable after an additional 6 mo of follow-up.

Throughout this review readers might wonder why well-conducted clinical trials evaluating the same therapeutic options result in this heterogeneity of clinical outcomes. How can a general recommendation be formulated for the successful management of CP/CPPS? Published data of randomized placebo/sham-controlled trials were pooled and subjected to meta-analysis [6] and [7]. No recommendations for monotherapies can be made based on these results. Data suggest that the combination of α-blockers and antibiotics may have a decent therapeutic effect with regard to symptom scores for selected patients [6] . However, certain limitations have to be taken into account when data synthesis in the form of a meta-analysis is performed. Some studies represent small single-center trials with inadequate control groups and blinding. According to basic characteristics, duration of disease and prior treatments are not documented. This makes the interpretation of this heterogeneous pool of data difficult and needs to be considered when recommendations are formulated.

UPOINT represents a novel 6-point clinical phenotyping system for the management of CP/CPPS. It profiles patients and indicates individual treatment targets to implement an individualized multimodal therapeutic regimen. The six UPOINT domains comprise Urinary symptoms, Psychological dysfunction, Organ-specific symptoms, Infection, Neurologic/systemic conditions, and Tenderness of muscles ( Fig. 3 ) [44], [45], [46], and [47]. UPOINT is able to discriminate clinical phenotypes, and positive domains appear to correlate with symptom severity and duration of disease [45] . Clinical results indicate a correlation between the number of positive UPOINT domains and total NIH-CPSI score [48] and [49]. With sexual dysfunction as a common condition affecting 40–70% of men with CP/CPPS [50], [51], [52], [53], and [54], the inclusion of an additional domain for Sexual dysfunction was proposed and evaluated. The modified UPOINTs algorithm has been suggested to support an optimized stratification of individual phenotypic profiles. However, clinical studies attempting to confirm an improved correlation between positive UPOINTs domains and symptom severity revealed heterogeneous results [48], [55], [56], and [57].

Most clinical trials conducted so far speak in favor of the extended UPOINTs approach. First studies suggest that the multimodal treatment guided by UPOINT leads to a significant improvement of symptoms and quality of life [58] . In a prospective study including a cohort of 100 men positive for a minimum of three UPOINT domains, clinical response to a phenotypically directed multimodal treatment was evaluated by a change in NIH-CPSI score. Almost 84% of patients met the primary end point of at least a 6-point change in total NIH-CPSI score with a median follow-up of 50 wk. All NIH-CPSI subdomains comprising scores for pain, urinary symptoms, and quality of life were significantly improved (each p ˂ 0.0001). Although first results are promising, further clinical RCTs are warranted for a complete validation of the UPOINTs approach. Categorization and treatment options directed by UPOINTs phenotype are depicted in Figure 3 .

In this section we introduce three index patients diagnosed with CP/CPPS. This selection may represent the most frequent clinical presentations in daily routine. Applying the UPOINTs algorithm, we have formulated our best practice recommendations based on published data in concert with expert opinion.

A 42-year-old man presents with modest perineal discomfort radiating to both testicles. He complains about hesitancy and a slow stream. In the last 2 yr he had two episodes of an acute bacterial prostatitis that were treated with an antimicrobial for 2 wk each time. The patient explains that sometimes his symptoms flare up and resolve partially on antibiotics. On digital rectal examination (DRE), the prostate feels slightly enlarged, and the patient reports moderate tenderness to palpation. Laboratory testing including PSA and C-reactive protein (CRP) was normal. A two-glass test is performed, and no pathogen is detected. Post–prostatic massage urine is positive for leukocytes, and microscopy shows an inflammatory pattern. Prostate volume as determined by transrectal ultrasonography is about 30 ml. Peak urinary flow rate is 14 ml/s with a voided urine volume of 300 ml. Postvoid residual urine volume is 80 ml. The patient is on no regular medication.

Table 3 shows the phenotypic evaluation according to UPOINTs and the resulting treatment plan.

Table 3 Phenotypic evaluation and recommendations on treatment

| Diagnosis | CP/CPPS category IIIA |

|---|---|

| UPOINTs | |

| U | Hesitancy, weak stream |

| P | NA |

| O | Tenderness to palpation, flares |

| I | NA |

| N | NA |

| T | NA |

| s | NA |

| Treatment | |

| U | α-Blockers |

| O | Pollen extract and/or quercetin, NSAID for flares |

CP/CPPS = chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome; NA = not applicable; NSAID = nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

A 46-year-old man presents with modest perineal discomfort. The patient complains about hesitancy and a slow stream, which has been increasing in recent years along with an increase in perineal pain. He wakes up at least three times a night to urinate. He is sexually active and describes post-ejaculatory pain. On DRE the prostate feels normal, but the patient reports moderate tenderness to palpation. Laboratory testing including PSA and CRP is normal. A two-glass test is performed, but no signs of inflammation or bacterial infection are detected. Prostate volume as determined by transrectal ultrasonography is about 30 ml. Peak urinary flow rate is 12 ml/s with a voided urine volume of 250 ml. Postvoid residual urine volume is 120 ml. The patient is on no regular medication.

Table 4 shows the phenotypic evaluation according to UPOINTs and the resulting treatment plan.

Table 4 Phenotypic evaluation and recommendations on treatment

| Diagnosis | CP/CPPS category IIIB |

|---|---|

| UPOINTs | |

| U | Hesitancy, weak stream |

| P | NA |

| O | Tenderness to palpation, perineal discomfort |

| I | NA |

| N | NA |

| T | Perineal and pelvic muscle tenderness |

| s | NA |

| Treatment | |

| U | α-Blockers |

| O | Pollen extract and/or quercetin |

| T | Local heat therapy (cushion, pads), physiotherapy/pelvic floor relaxation |

CP/CPPS = chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome; NA = not applicable.

A 42-year-old man presents with modest perineal discomfort. Burning sensations are radiating to the abdomen and his back. The patient is anxious about his symptoms and fears a malignant process. His worries and doubts have been progressing in recent years. It started with his diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome. The development of chronic fatigue syndrome and intermediate episodes of migraine headaches are secondary findings that emerged in the last 3 yr. The patient admits that depressive episodes have become more frequent since the perineal pain started. On DRE the prostate feels normal. The pelvic floor is tender to touch. Laboratory testing including PSA and CRP is normal. A two-glass test is performed, but no signs of inflammation or bacterial infection are detected. The patient is on no regular medication.

Table 5 shows the phenotypic evaluation according to UPOINTs and the resulting treatment plan.

Table 5 Phenotypic evaluation and recommendations on treatment

| Diagnosis | CP/CPPS category III B |

|---|---|

| UPOINTs | |

| U | NA |

| P | Depression, catastrophizing |

| O | NA |

| I | NA |

| N | Neuropathic pain |

| T | Perineal and pelvic muscle tenderness |

| s | NA |

| Treatment | |

| P | Psychological support, referral to psychologist (cognitive behavioral therapy), tricyclic antidepressants |

| N | Pregabalin, tricyclic antidepressants, acupuncture |

| T | Physiotherapy/pelvic floor relaxation, muscle relaxants |

CP/CPPS = chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome; NA = not applicable.

In this comprehensive review we presented our current understanding of best practice management of symptomatic CP/CPPS based on published data in concert with expert opinion. We have not been able to decipher the pathophysiology underlying CP/CPPS to identify common key targets for treatment. This has made the management of this bothersome condition very challenging for both clinicians and patients. Our inability to formulate recommendations with a high grade of evidence for efficient monotherapies reflects the main problem. Scientific reports do not speak in favor of a common etiology applying to all forms of CP/CPPS. A multifactorial genesis appears to contribute to an individual multifaceted complex of symptoms for every patient diagnosed with CP/CPPS. The current understanding of the management of CP/CPPS strongly suggests a multimodal therapeutic approach addressing the individual clinical phenotypic profile. More RCTs are warranted for validation of this phenotype-directed treatment. Although its role for the management of CP/CPPS has still to be defined, it appears to be a promising and effective alternative to the current empirical sequential monotherapy.

Author contributions: Giuseppe Magistro had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Magistro, Nickel.

Acquisition of data: Magistro, Wagenlehner, Nickel.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Magistro, Wagenlehner, Grabe, Weidner, Stief, Nickel.

Drafting of the manuscript: Magistro, Wagenlehner, Grabe, Weidner, Stief, Nickel.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Magistro, Wagenlehner, Grabe, Weidner, Stief, Nickel.

Statistical analysis: None.

Obtaining funding: None.

Administrative, technical, or material support: None.

Supervision: Magistro, Wagenlehner, Nickel.

Other (specify): None.

Financial disclosures: Giuseppe Magistro certifies that all conflicts of interest, including specific financial interests and relationships and affiliations relevant to the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript (eg, employment/affiliation, grants or funding, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, royalties, or patents filed, received or pending), are the following: J. Curtis Nickel is a consultant/researcher for Pfizer, Astellas, Ferring, Farr Laboratories, Taris, Allergan, Aquinox, Lilly, NIH/NIDDK, and CIHR. Florian M.E. Wagenlehner is a consultant/researcher for Astellas, Astra-Zeneca, Bionorica, Calixa, Cerexa, Cernelle, Cubist, Galenus, Leo-Pharma, Merlion, OM-Pharma, Pierre Fabre, Rosen Pharma, and Zambon. The other authors having nothing to disclose.

Funding/Support and role of the sponsor: None.

Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) and pelvic pain due to pathologies of the prostate have always considerably affected quality of life of men of all ages. Epidemiologic data suggest that the prevalence of prostatitis-like symptoms is comparable with ischemic heart disease and diabetes mellitus. The rate of prostatitis-like symptoms ranges from 2.2% to 9.7%, with a mean prevalence of 8.2% [1] .

In the late 1990s, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) established a consensus definition and classification system for prostatitis [2] . It has been accepted internationally in both clinical practice and research ( Table 1 ). Prostatitis syndromes comprise infectious forms (acute and chronic), the chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CPPS), and asymptomatic prostatitis [2] . In <10% of patients with prostatitis syndrome, a causative uropathogenic organism can be detected. An acute bacterial episode will lead to chronic bacterial prostatitis in 10% and to CPPS in a further 10% [3] . CPPS accounts for most of the prostatitis-like symptoms in >90% of men.

Table 1 National Institutes of Health classification system for prostatitis syndromes

| Category | Nomenclature |

|---|---|

| I | Acute bacterial prostatitis |

| II | Chronic bacterial prostatitis |

| III | Chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome |

| IIIA | Inflammatory |

| IIIB | Noninflammatory |

| IV | Asymptomatic prostatitis |

The National Institutes of Health Chronic Prostatitis Symptom Index (NIH-CPSI) presents an objective assessment tool and outcome measure for prostatitis-like symptoms [4] and [5]. The introduction of a generally accepted classification system and an objective outcome measure led to a plethora of clinical trials that made one particular point clear. Although the treatment of bacterial prostatitis obviously relies on the adequate use of antimicrobial agents, successful management of CPPS has always been a formidable task. The complex and heterogeneous pathophysiology of CPPS is poorly understood. Consequently, an effective monotherapy is not available, which makes the management of CPPS challenging for both physicians and patients. Clinical trials were not able to identify a monotherapy with significant clinical efficacy. A meta-analysis evaluating data of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) using the NIH-CPSI as a common outcome measure failed to derive a guideline statement on the treatment of this bothersome condition [6] and [7].

The dilemma of limited success of clinical trials prompted us to provide a comprehensive review with expert interpretations of the available literature to formulate best practice recommendations. Introducing index patients diagnosed with CPPS, we demonstrate how these recommendations might be applied in clinical practice. The main objective of this review is to present best practice recommendations for the management of CPPS (NIH type III).

We performed a systematic review of the literature in the PubMed and Cochrane database according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis statement [8] . We searched for RCTs and meta-analyses on the treatment of chronic prostatitis CP/CPPS from January 1988 to December 2014. A detailed description of the search strategy is presented in Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Figure 1. In addition, references of review articles were screened for possibly missed articles.