Context

A recent Cochrane Collaboration meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating the efficacy of different extracts of Serenoa repens in relieving lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) due to benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) concluded that these extracts were no more effective than placebo. However, among all Serenoa repens extracts, Permixon (Pierre Fabre Medicament, Paris, France) has the highest activity and the most accurate standards of drug preparation and extraction.

Objective

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of Permixon in the treatment of LUTS/BPH.

Evidence acquisition

A systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature was performed in January 2016 using the Medline, Scopus, and Web of Science databases, searching for the term Serenoa repens in all fields of the records. Only RCTs reporting on efficacy and safety of Permixon in the treatment of LUTS/BPH were selected.

Evidence synthesis

The systematic search identified 12 RCTs: 7 compared Permixon with placebo; 2 compared Permixon with tamsulosin; 2 compared Permixon plus tamsulosin with, respectively, placebo plus tamsulosin and tamsulosin alone; and 1 compared Permixon with finasteride. Permixon was significantly more effective than placebo in reducing the number of nocturnal voids (weighted mean difference [WMD] −0.31; p = 0.03) and increasing maximum flow rate (Qmax; WMD 3.37; p < 0.0001). The rates of overall adverse events (odds ratio [OR] 1.12; p = 0.92) and withdrawal (OR 1.52; p = 0.60) were similar for Permixon and placebo. Permixon was as effective as tamsulosin monotherapy and short-term therapy with finasteride in improving International Prostate Symptom Score (WMD 1.15; 95% confidence interval [CI], −1.11 to 3.40; p = 0.32) and Qmax (WMD −0.16; 95% CI, −0.60 to 0.28; p = 0.48). The combination of Permixon and tamsulosin was more effective than Permixon alone for relieving LUTS (WMD 0.31; 95% CI, 0.13–0.48; p < 0.01) but not for improving Qmax(WMD 0.10; 95% CI −0.02 to 0.21; p = 0.10). Permixon had a favorable safety profile, with a very limited impact with regard to ejaculatory dysfunction compared with tamsulosin (0.5% vs 4%; p = 0.007) and with regard to decreased libido and impotence compared with short-term finasteride (2.2% and 1.5% vs 3% and 2.8%, respectively).

Conclusions

The conclusions of the recent Cochrane meta-analysis on Serenoa repens in the treatment of LUTS/BPH apparently do not apply to Permixon. Our meta-analysis showed that Permixon decreased nocturnal voids and Qmax compared with placebo and had efficacy in relieving LUTS similar to tamsulosin and short-term finasteride. Moreover, Permixon had a favorable safety profile with a very limited impact on sexual function, which is significantly affected by all other drugs used to treat LUTS/BPH.

Patient summary

A systematic review of the literature showed that Permixon was effective for relieving urinary symptoms due to prostate enlargement and improving urinary flow compared with placebo. Permixon had efficacy similar to tamsulosin and short-term finasteride in relieving urinary symptoms. Permixon was well tolerated and had a very limited impact on sexual function.

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is a common cause of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) in adult men. α-Blockers, 5α-reductase inhibitors (5-ARIs), antimuscarinics, and phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors, either alone or in combination, are the standard medical treatments for patients with uncomplicated bothersome LUTS/BPH unresponsive to behavioral management [1] and [2].

Phytotherapy is currently prescribed in both Europe and the United States for the treatment of male LUTS/BPH, and a 2010 publication reported that approximately 17% of the patients with LUTS used this category of drug as monotherapy [3]. Moreover, a recent population study from France suggested that phytotherapy was taken by 32% of patients using combination therapies [4]. Extracts of saw palmetto, known as Serenoa repens, are the most commonly used phytotherapeutic compounds. Specifically, Serenoa repens is a lipidosterolic extract of the berry of the dwarf palm tree that has antiandrogenic action, antiproliferative proapoptotic effects, and anti-inflammatory properties [5]. This last effect could be of interest considering the most recent in vitro and in vivo studies highlighting the potential role of inflammation in LUTS/BPH [6].

A recent Cochrane Collaboration meta-analysis pooled all available randomized controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating all of the different extracts of Serenoa repens and demonstrated that they were no more effective than placebo in relieving male LUTS/BPH [7]. However, quality of plant extracts is strictly related to the quality of the botanical source as well as to the method of preparation and drug extraction. Consequently, different products derived from the same plant can have different activity and different safety profiles [8]. Some preclinical studies confirmed that major differences exist among different brands of Serenoa repens. Specifically, Habib and Wyllie [9] compared the concentrations of free fatty acids, methyl and ethyl esters, long-chain esters, and glycerides in 14 brands of Serenoa repens and demonstrated major differences among the extracts; Permixon (Pierre Fabre Medicament, Paris, France) had the highest percentage of free fatty acids considered to be responsible, at least in part, for the therapeutic effects of Serenoa repens. Moreover, Scaglione et al. [10] evaluated the efficacy of different batches of seven different Serenoa repens extracts in inhibiting 5α-reductase type I and II enzymes and demonstrated major differences among the different extracts and between different batches of the same extracts, with Permixon showing the highest efficacy and the lowest variability from batch to batch. In a recent publication by the same group [11], among nine more Serenoa repens extracts that were different from those studied previously, Permixon showed the highest activity, reinforcing the evidence that potency differs among extracts. Taken together, these data raise questions about the conclusions of the Cochrane meta-analysis because of the pooling of different, potentially nonbioequivalent extracts, as also suggested by the European Association of Urology guidelines [1].

With a focus solely on Permixon, which showed the highest efficacy in preclinical studies and has the most accurate standards of drug preparation and extraction, we performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of all RCTs assessing the efficacy and safety of Permixon for the treatment of LUTS/BPH.

The systematic review of the literature was performed in January 2016 using the Medline, Scopus, and Web of Science databases. All searches used free-text protocols searching for the keyword Serenoa repens in all record fields. No limitations were used. Moreover, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews was also searched using the same keyword.

Three authors assessed the eligibility of the papers relevant to the review topic. Specifically, all RCTs reporting on efficacy and safety from the use of Permixon in LUTS/BPH were selected. One author extracted information on patients, interventions, and outcomes that was checked by other two authors, and discrepancies were resolved by open discussion with the senior author. The quality of the retrieved RCTs was assessed using the Jadad score [12].

Meta-analysis was conducted using Review Manager software v.5.0 (Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK). Statistical heterogeneity was tested using the χ2 test. A value of p < 0.10 was used to indicate heterogeneity. Random-effects models were used for the meta-analyses. The results were expressed as weighted mean difference (WMD) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) for continuous outcomes and as an odds ratio (OR) with a 95% CI for dichotomous variables. The presence of publication bias was evaluated through a funnel plot [13].

The study complies with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement [14].

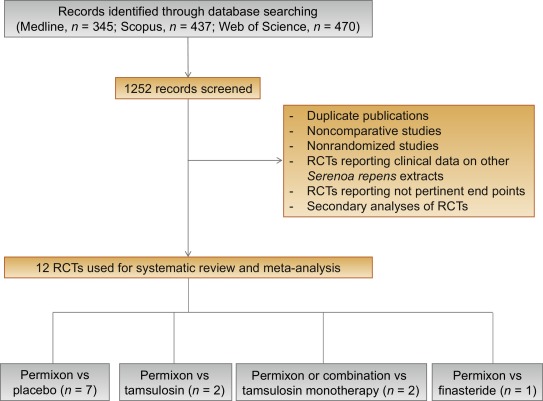

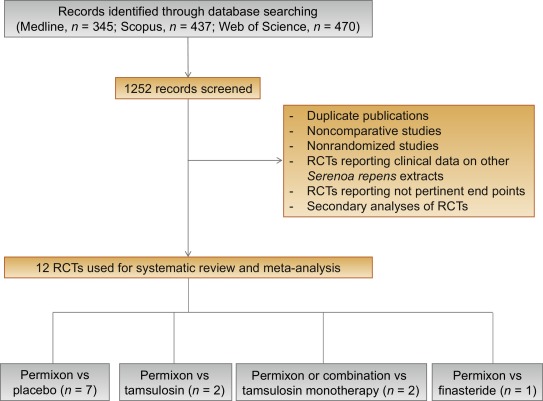

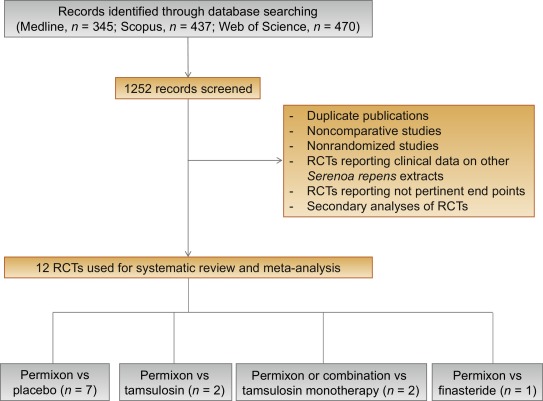

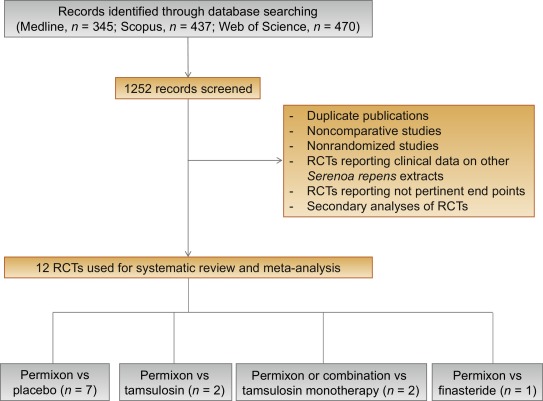

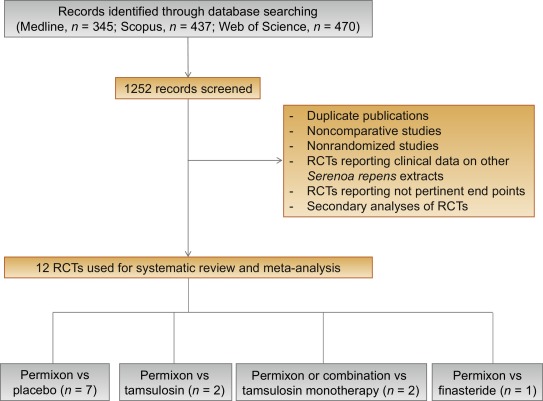

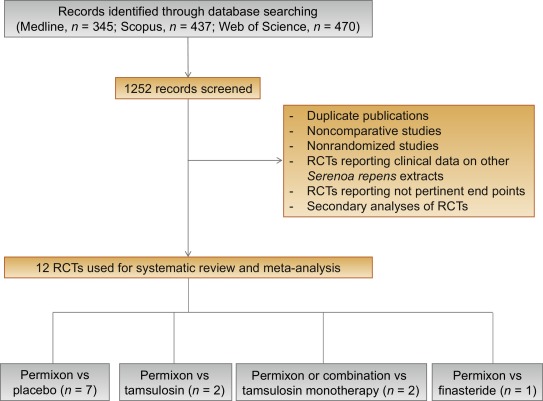

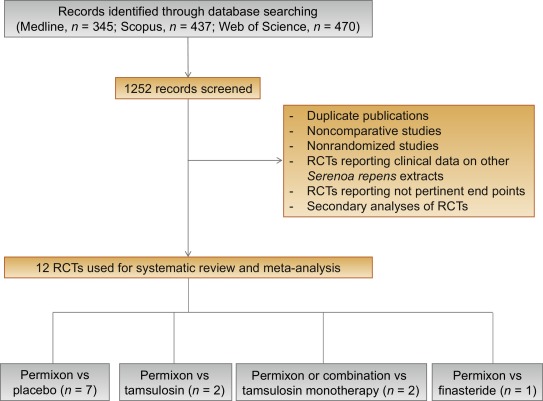

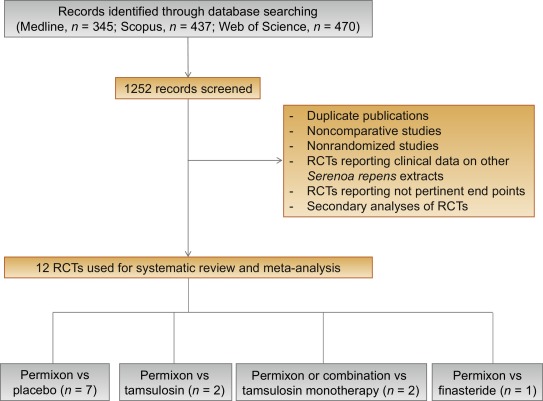

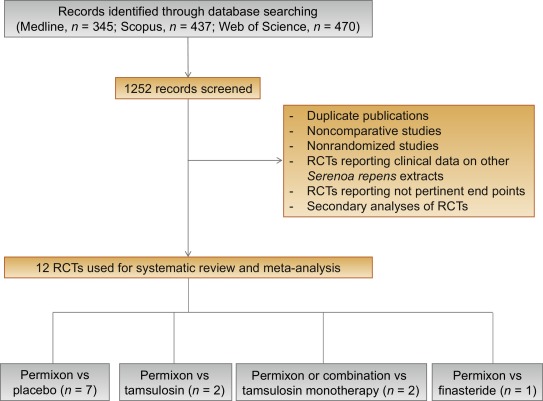

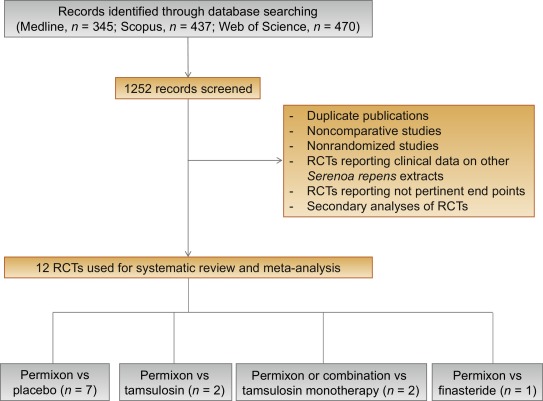

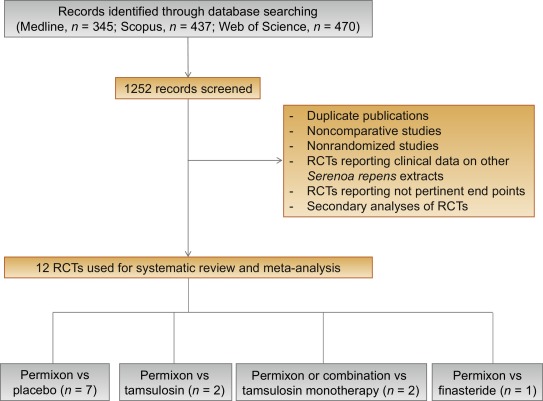

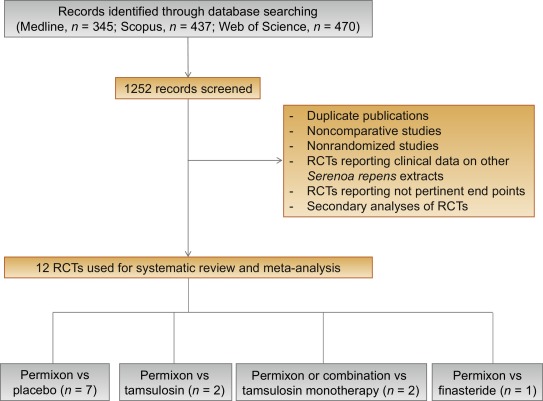

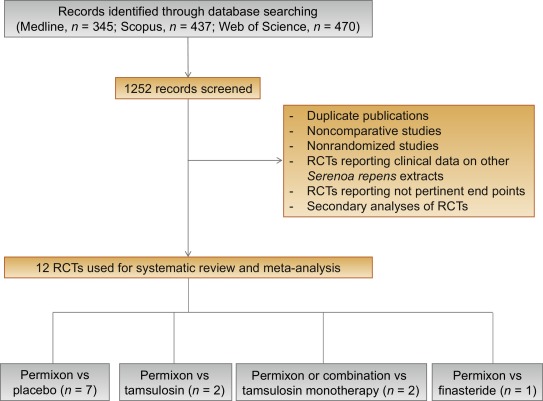

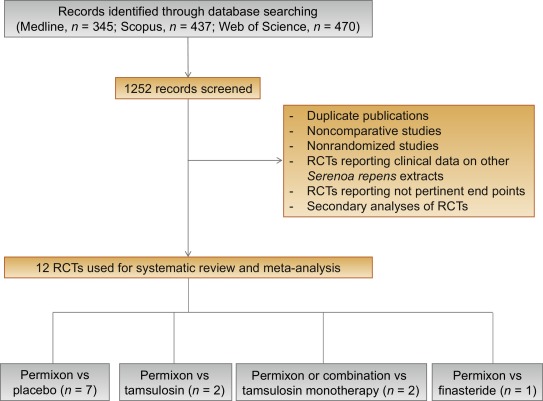

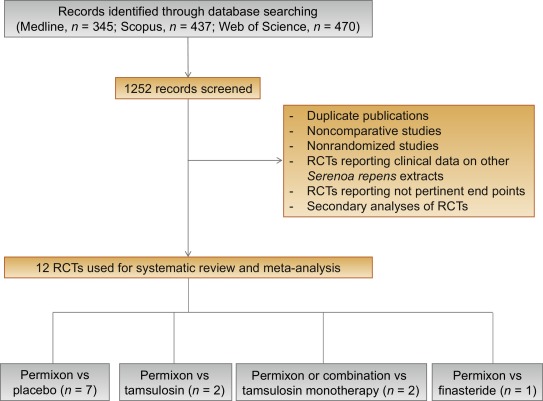

Figure 1 summarizes the literature review process that led to the identification of the 12 RCTs used in the meta-analysis. Specifically, seven RCTs compared Permixon with placebo [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], and [21], two RCTs compared Permixon with tamsulosin [22] and [23], two RCTs compared Permixon plus tamsulosin with placebo plus tamsulosin [24] and with tamsulosin alone [25], and a single RCT compared Permixon with finasteride [26]. Among these publications, there were four RCTs of good methodological quality (level of evidence 2) [22], [23], [24], and [26] and eight RCTs of poor methodological quality (level of evidence 3) [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], and [25]. Clinically speaking, all studies but three [22], [24], and [25] evaluated short-term treatment schedules; standard outcome measures, such as the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) and the American Urological Association symptom index, were used in only five studies [22], [23], [24], [25], and [26].

Table 1 summarizes the studies reporting the efficacy and safety of Permixon in comparison to placebo [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], and [21].

Table 1

Efficacy and safety data of studies comparing Permixon with placebo

| Study | Arms | Duration, wk | RCT | Nocturnal voids at study end, mean ± SD | Change in nocturnal voids from baseline, mean ± SD | Qmax, ml/s, mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Efficacy data | ||||||

| Boccafoschi and Annoscia, 1983 [15] | Permixon (n = 11) Placebo (n = 11) |

8 | Yes | 1.8 ± 2.01 2.1 ± 1.79 |

NR | 13.7 ± 7.03 12.2 ± 7.03 |

| Emili et al., 1983 [16] | Permixon (n = 15) Placebo (n = 15) |

4 | Yes | 1.67 ± 0.98 2.33 ± 1.11 |

NR | 13.7 ± 3.56 9.4 ± 2.72 |

| Mandressi et al., 1983 [17] | Permixon (n = 20) Placebo (n = 20) Pygeum (n = 20) |

4 | Yes | NR | −2.06 (−42%) −0.96 (−4%) −1.6 (−38%) |

NR |

| Cukier et al., 1985 [18] | Permixon (n = 71) Placebo (n = 76) |

10 | Yes | 2.2 ± 1.97 2.9 ± 1.99 |

NR | NR |

| Tasca et al., 1985 [19] | Permixon (n = 14) Placebo (n = 13) |

8 | Yes | 0.9 ± 2.02 1.9 ± 1.99 |

NR | 16.2 ± 7.03 11.8 ± 7.03 |

| Reece Smith et al., 1986 [20] | Permixon (n = 33) Placebo (n = 37) |

12 | Yes | 1.86 ± 1.2 1.9 ± 1.4 |

NR | NR |

| Descotes et al., 1995 [21] | Permixon (n = 82) Placebo (n = 94) |

4 | Yes | 1.4 ± 1.7 1.5 ± 1.1 |

−0.7 −0.3 |

15.3 ± 11.89 13.5 ± 8.59 |

| Safety data | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Arms | Overall drug-related adverse event, % | Libido decrease, % | Withdrawal, % | Withdrawal due to adverse events, % |

| Boccafoschi and Annoscia, 1983 [15] | Permixon (n = 11) Placebo (n = 11) |

0 10 |

NR | 0 0 |

0 0 |

| Emili et al., 1983 [16] | Permixon (n = 15) Placebo (n = 15) |

0 0 |

NR | 0 0 |

0 0 |

| Tasca et al., 1985 [19] | Permixon (n = 15) Placebo (n = 15) |

6.7 15 |

NR | 6.7 13.3 |

6.7 0 |

| Reece Smith et al., 1986 [20] | Permixon (n = 40) Placebo (n = 40) |

10 0 |

0 0 |

17 7 |

5 0 |

NR = not reported; Qmax = maximum urinary flow rate; RCT = randomized controlled trial; SD = standard deviation.

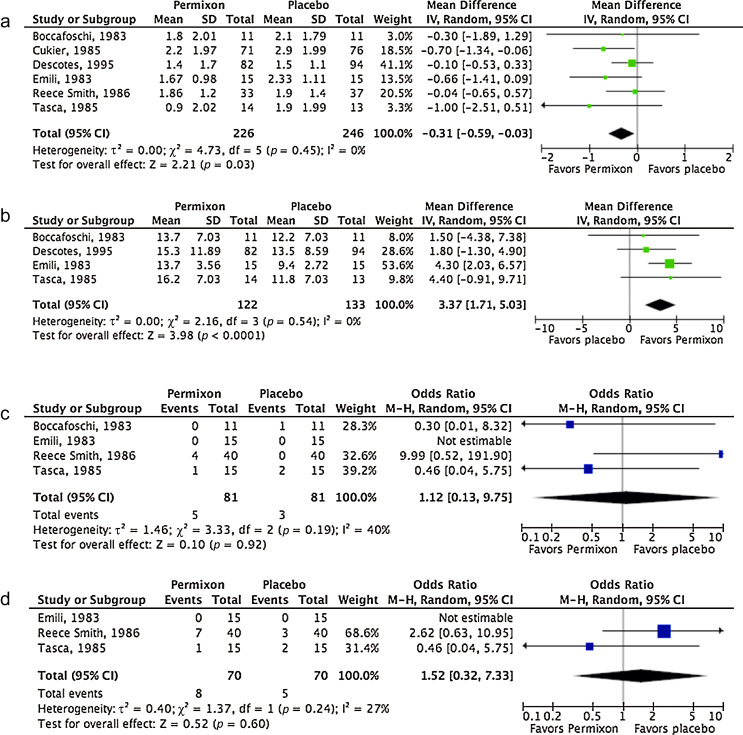

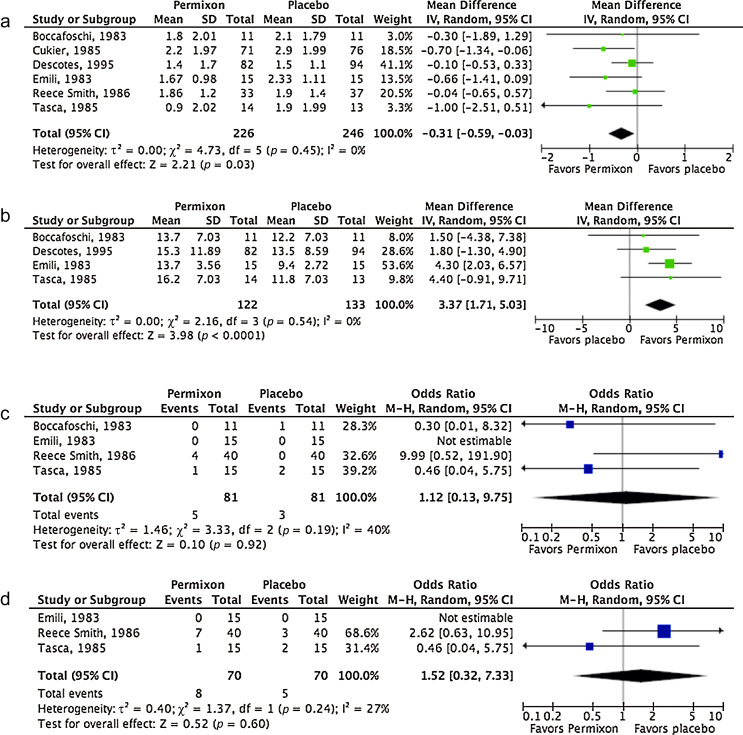

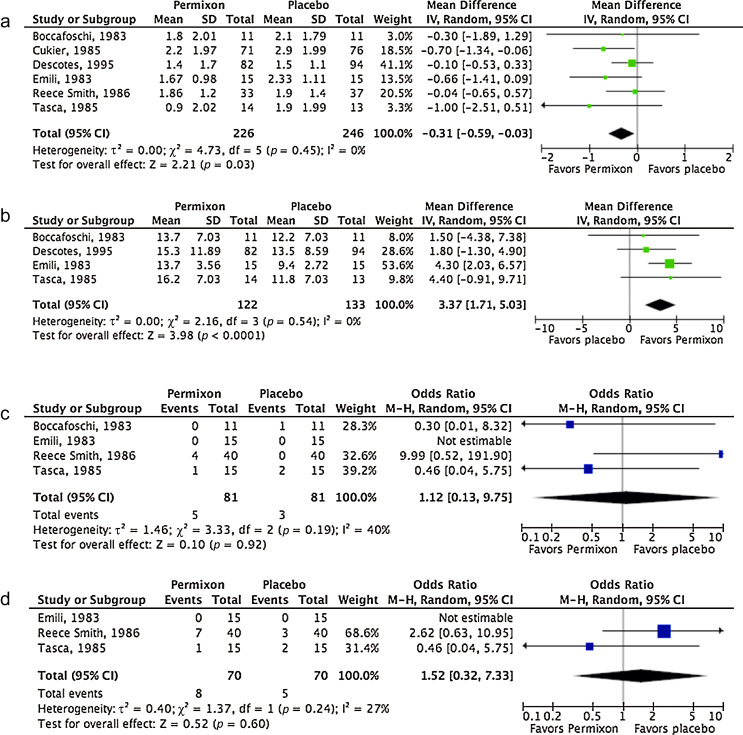

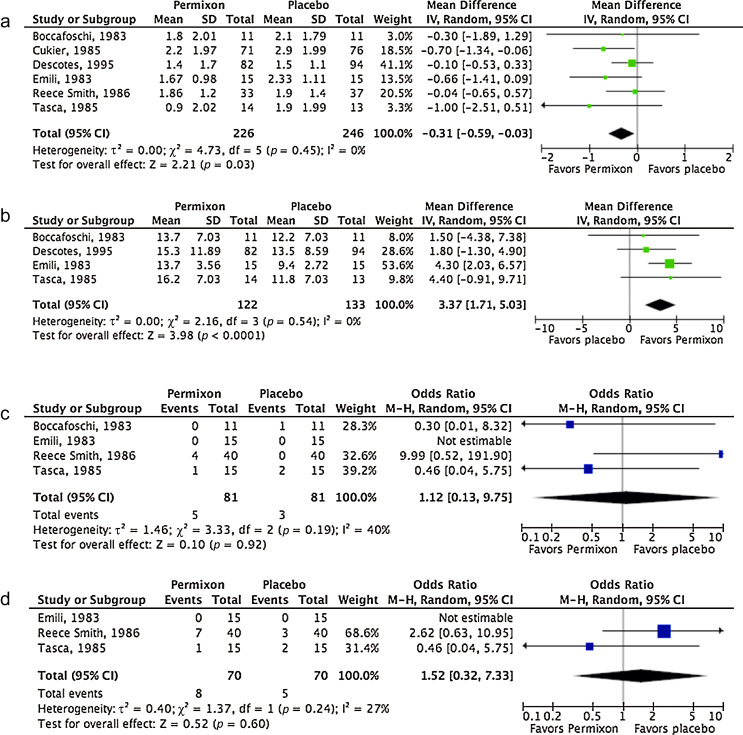

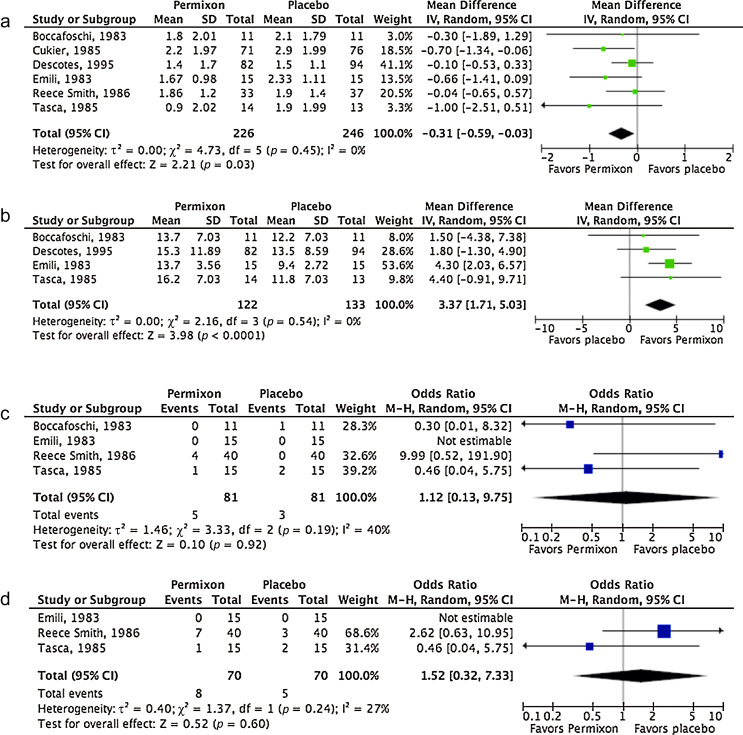

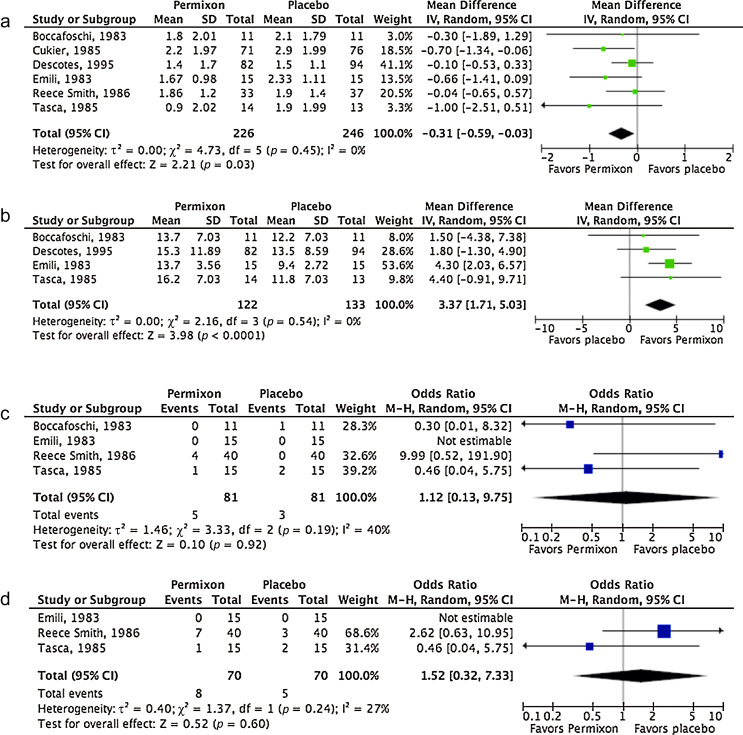

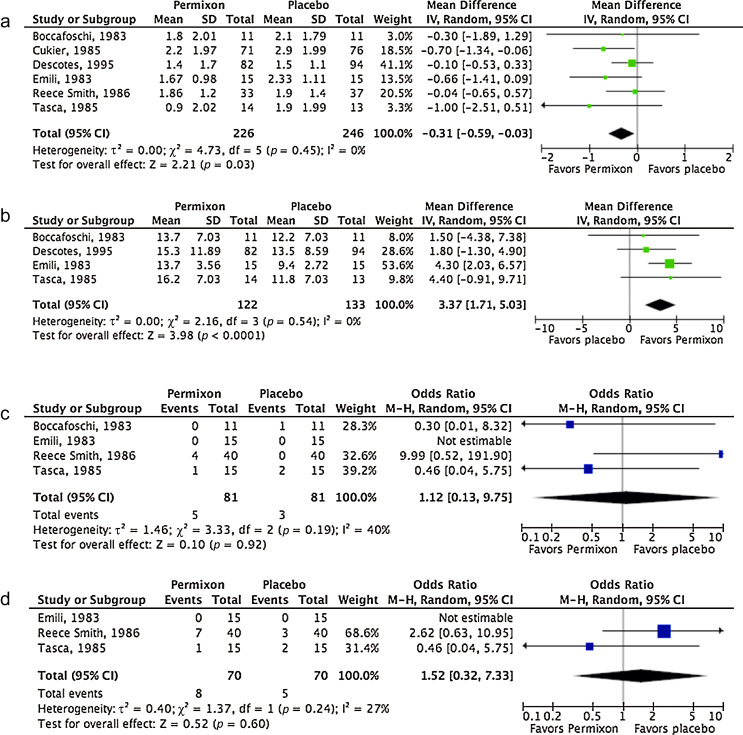

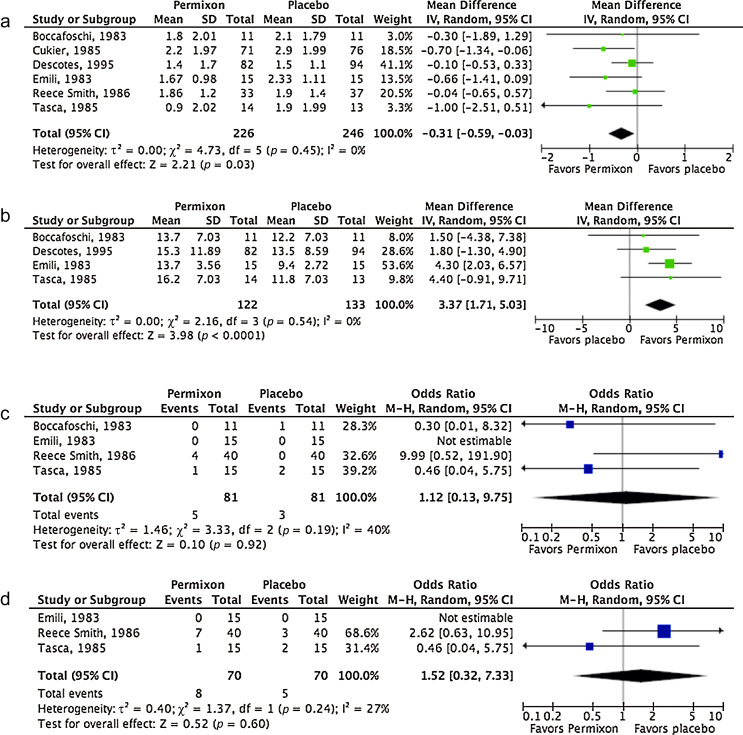

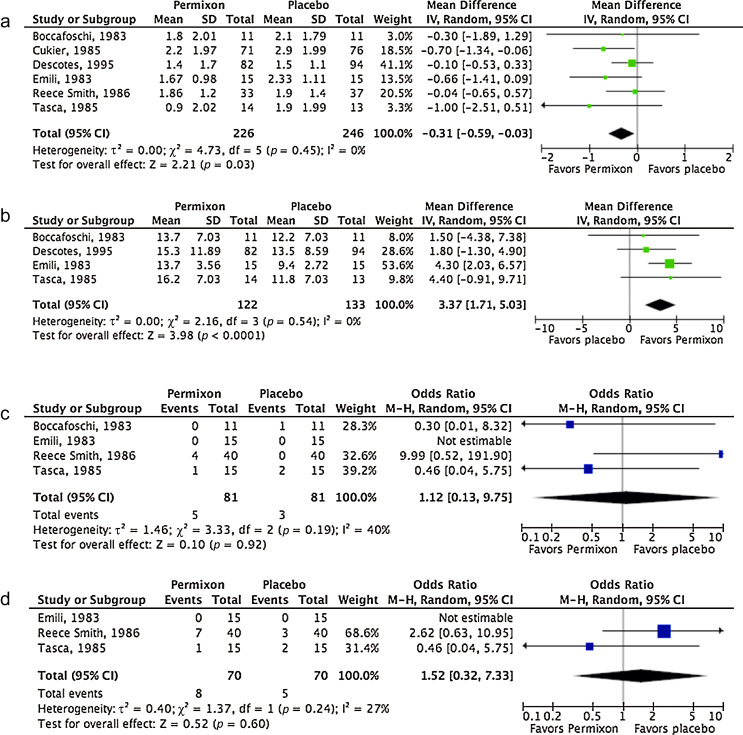

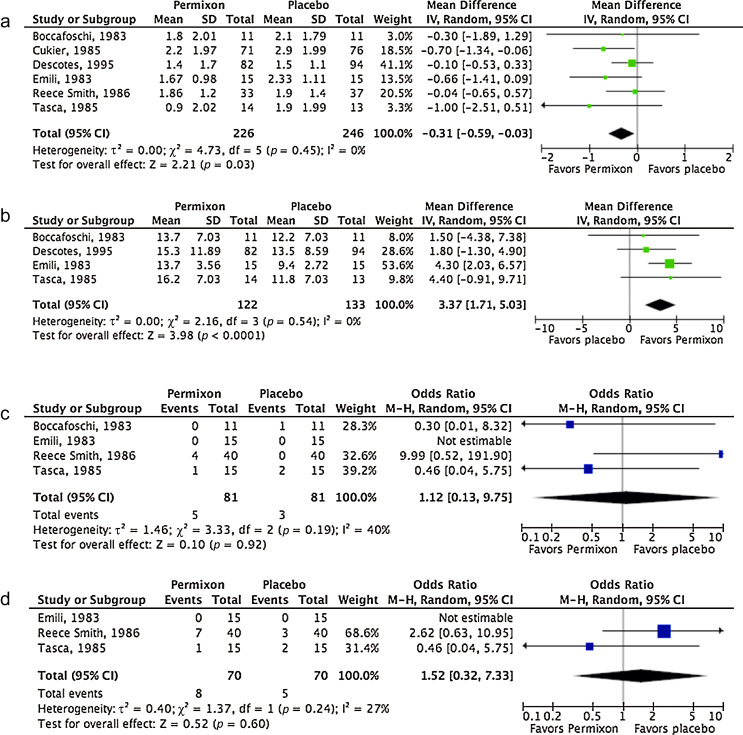

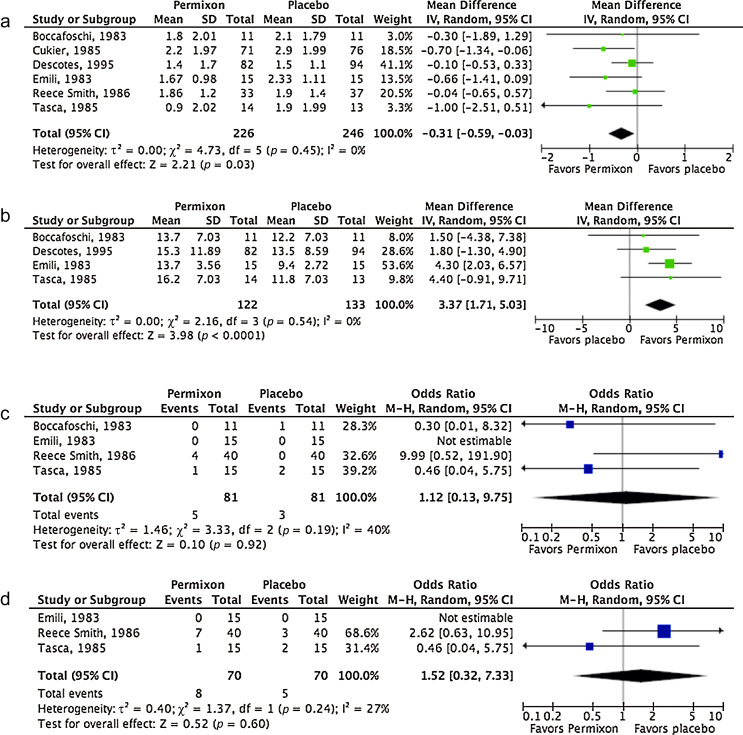

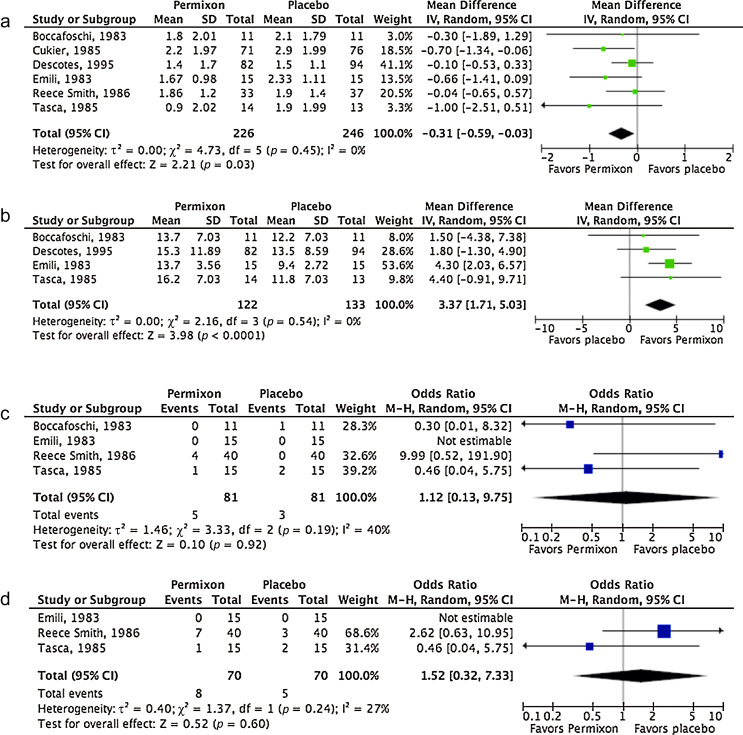

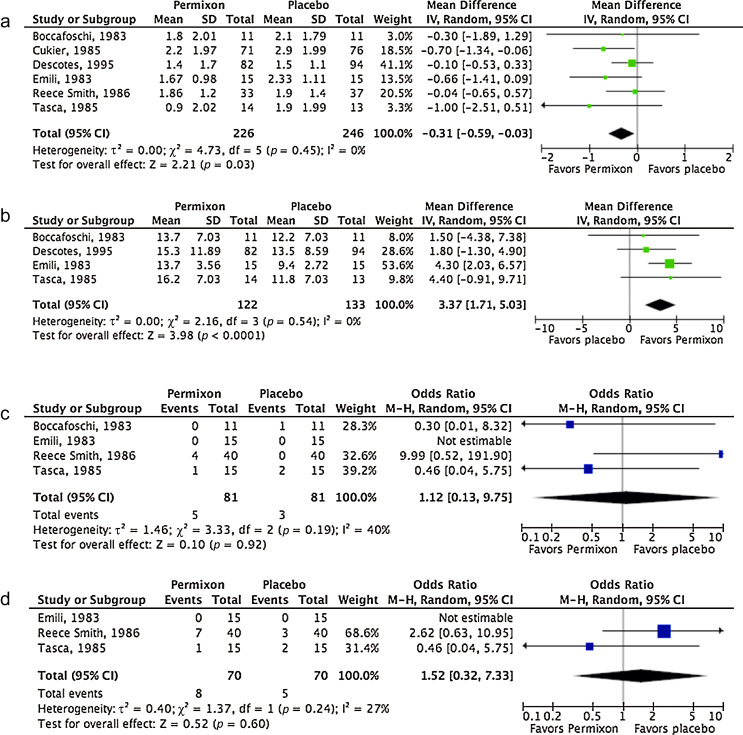

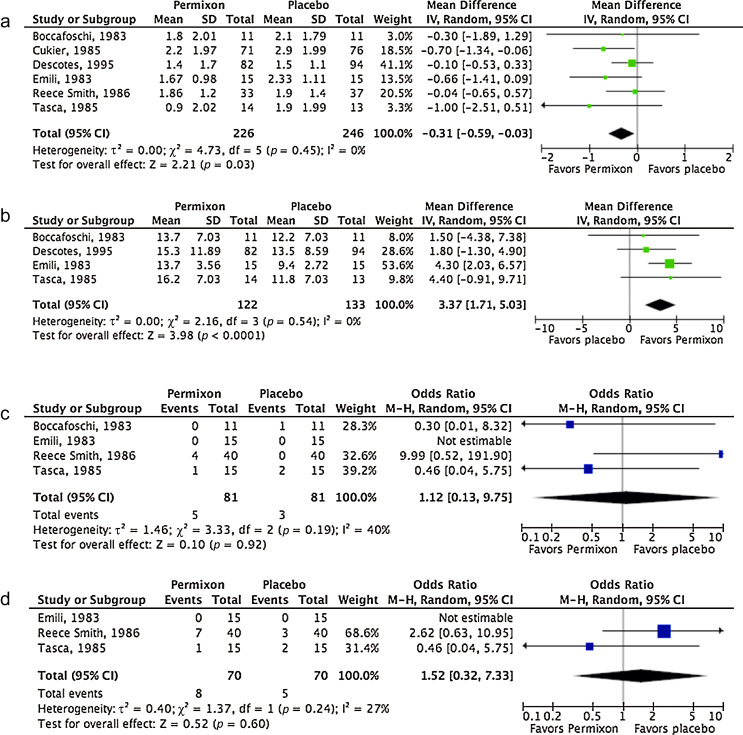

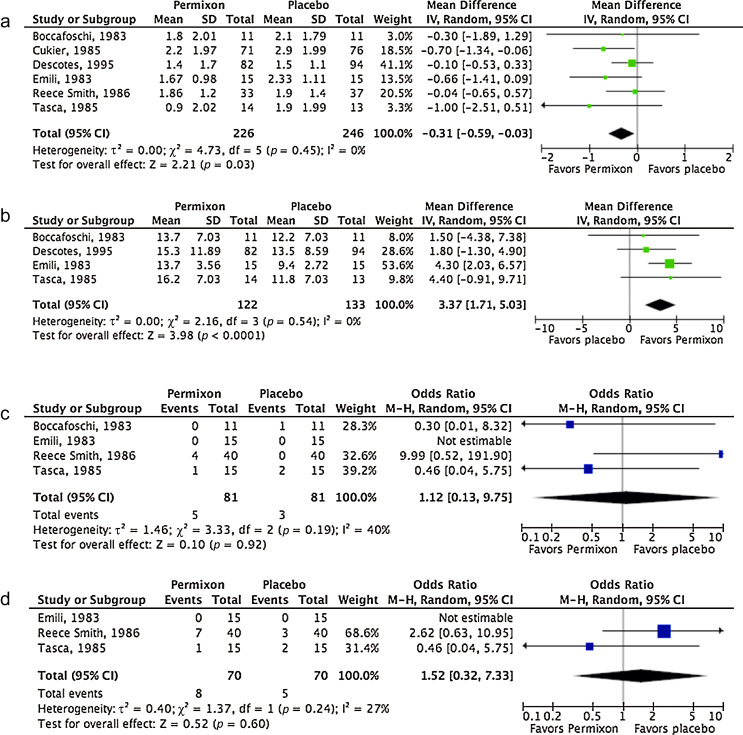

The number of nocturnal voids at study end were significantly lower with Permixon (WMD −0.31; 95% CI, −0.59 to −0.03; p = 0.03). Moreover, maximum urinary flow rate (Qmax) at study end was significantly higher in the patients treated with Permixon (WMD 3.37; 95% CI, 1.71–5.03; p < 0.0001). With regard to safety, the overall adverse event rates were similar for Permixon and placebo (OR 1.12; 95% CI, 0.13–9.75; p = 0.92). Finally, withdrawal rates were similar following Permixon or placebo (OR 1.52; 95% CI, 0.32–7.33; p = 0.60).

Figure 2 shows the forest plots for efficacy and safety data of Permixon in comparison to placebo.

Forest plots of comparisons in studies with Permixon versus placebo: (a) number of nocturnal voids at study end; (b) maximum urinary flow rate at study end; (c) rate of overall adverse events; (d) withdrawal rate.

CI = confidence interval; IV = inverse variance; M-H = Mantel-Haenszel; SD = standard deviation.

Table 2 summarizes the studies reporting efficacy and safety of Permixon or combination therapy compared with tamsulosin.

Table 2

Efficacy and safety data of studies comparing Permixon or combination therapy with tamsulosin

| Study | Arms | Duration, wk | RCT | Change in IPSS from baseline, mean ± SD | Change in IPSS storage subscore, mean ± SD | Change in IPSS voiding subscore, mean ± SD | Change in IPSS QoL score, mean ± SD | Nocturnal voids, mean ± SD | Qmax increase, ml/s, mean ± SD | PVR, ml, mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Efficacy data | ||||||||||

| Debruyne et al., 2002 [22] | Permixon (n = 340) Tamsulosin (n = 345) |

52 | Yes | −4.4 ± 5.5 −4.4 ± 5.1 |

−1.7 ± 2.8 −1.5 ± 2.4 |

−2.8 ± 3.7 −2.9 ± 3.7 |

NR | NR | 1.9 ± 4.8 1.8 ± 4.8 |

NR |

| Latil et al., 2015 [23] | Permixon (n = 102) Tamsulosin (n = 101) |

12 | Yes | −4.3 ± 3 −6.6 ± 3 |

NR | NR | −0.87 ± 1.6 −1.29 ± 1.6 |

NR | 1.77 ± 2.1 2.09 ± 2 |

15.2 ± 33.6 4.04 ± 34 |

| Glémain et al., 2002 [24] | Permixon plus tamsulosin (n = 157) Placebo plus tamsulosin (n = 159) |

52 | Yes | −6.0 ± 6 −5.2 ± 6.4 |

−1.9 ± 2.9 −1.9 ± 3.1 |

−4.1 ± 4.4 −3.3 ± 4.6 |

−1.3 ± 1.4 −1.0 ± 1.4 |

NR | 1.2 ± 4.6 1.3 ± 5.2 |

NR |

| Ryu et al., 2015 [25] | Permixon plus tamsulosin (n = 60) Tamsulosin (n = 60) |

52 | Yes | −5.8 ± 0.43 −5.5 ± 0.54 |

−1.9 ± 0.33 0.9 ± 0.3 |

−3.9 ± 0.41 −4.5 ± 0.42 |

−2.4 ± 0.43 −2.5 ± 0.4 |

NR | 2.1 ± 0.31 2.0 ± 0.26 |

8.3 ± 1.45 −10.6 ± 1.79 |

| Safety data | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Arms | Overall AEs, % | Withdrawal, % | Withdrawal due to AEs, % | Ejaculatory dysfunction, % | Postural hypotension, % | Headache, % | Dizziness, % |

| Debruyne et al., 2002 [22] | Permixon (n = 349) Tamsulosin (n = 354) |

66* 67* |

15 16 |

8 8 |

0.5 4 |

1 1 |

8 11 |

3 2 |

| Latil et al., 2015 [23] | Permixon (n = 102) Tamsulosin (n = 101) |

29 31 |

8 3 |

NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Glémain et al., 2002 [24] | Permixon plus tamsulosin (n = 168) Placebo plus tamsulosin (n = 161) |

16 10 |

18 20 |

4 3 |

8 5 |

1 0 |

NR | 2 2 |

| Ryu et al., 2015 [25] | Permixon plus tamsulosin (n = 60) Tamsulosin (n = 60) |

20 17 |

0 0 |

0 0 |

6 7 |

4 4 |

10 11 |

4 2 |

* These figures include both drug-related and drug-unrelated AEs.

AE = adverse event; IPSS = International Prostate Symptom Score; NR = not reported; PVR = postvoid residual urine; Qmax = maximum urinary flow rate; QoL = quality of life; RCT = randomized controlled trial; SD = standard deviation.

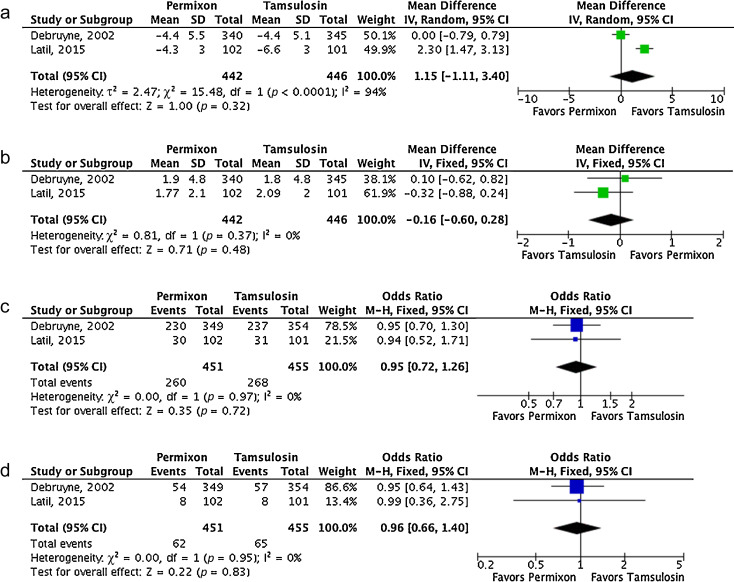

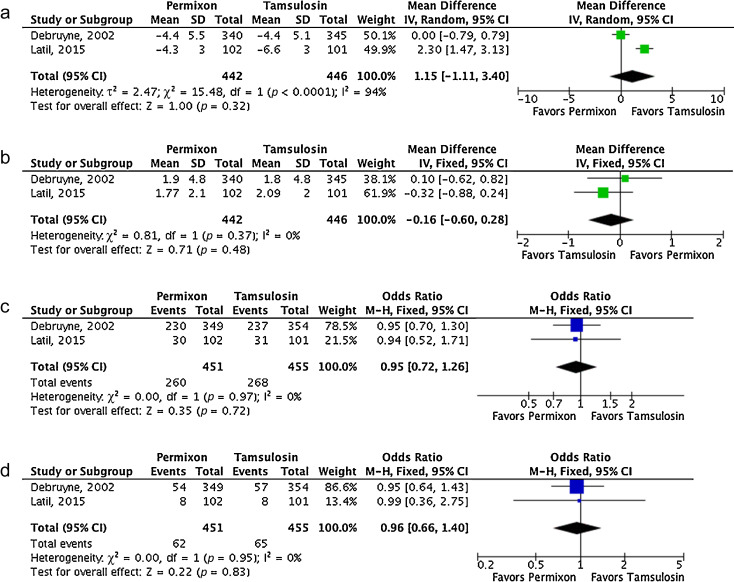

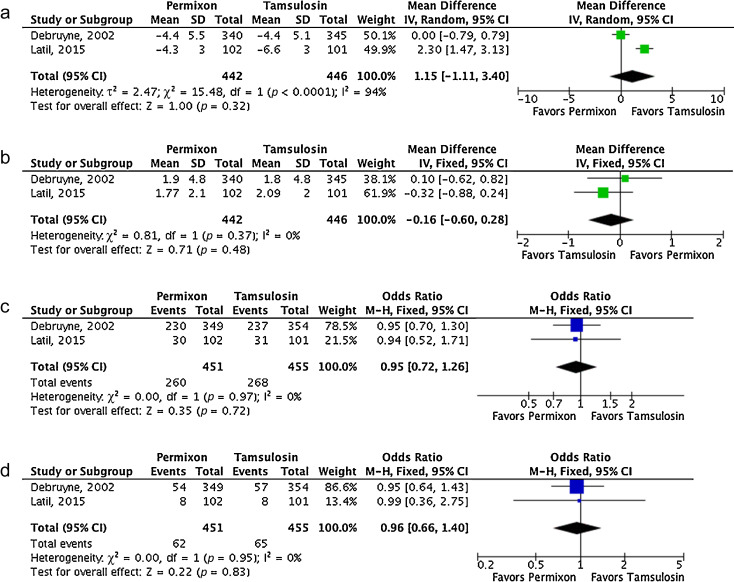

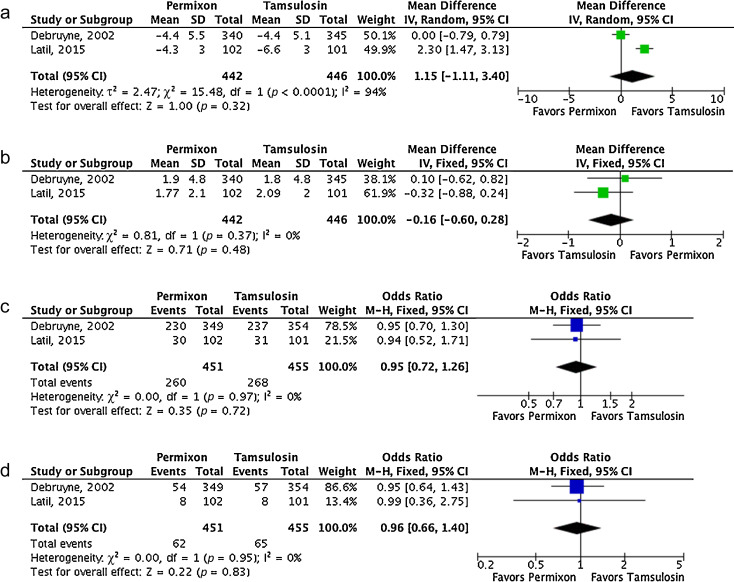

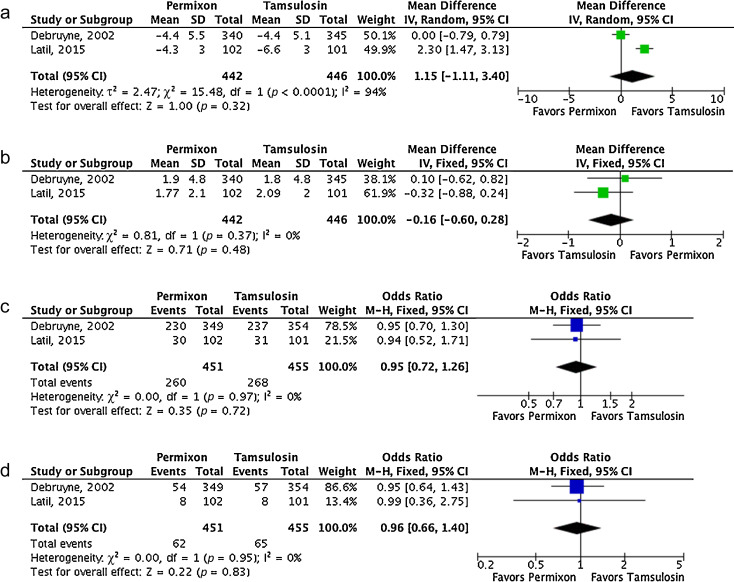

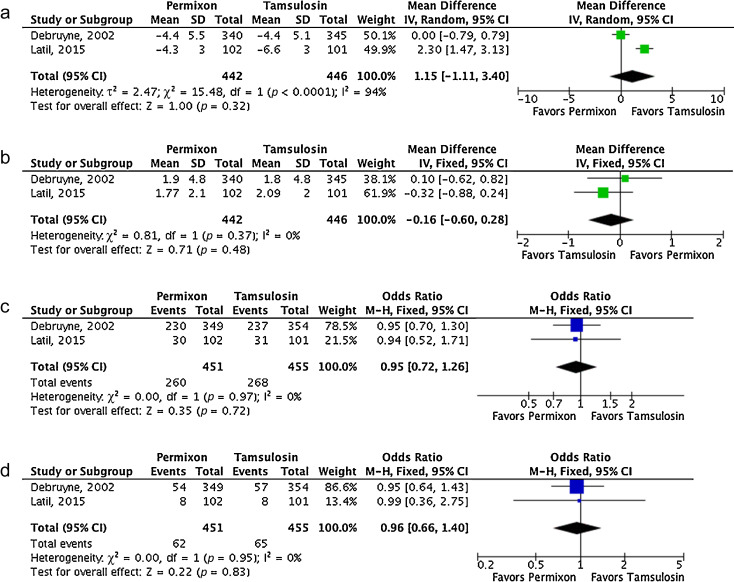

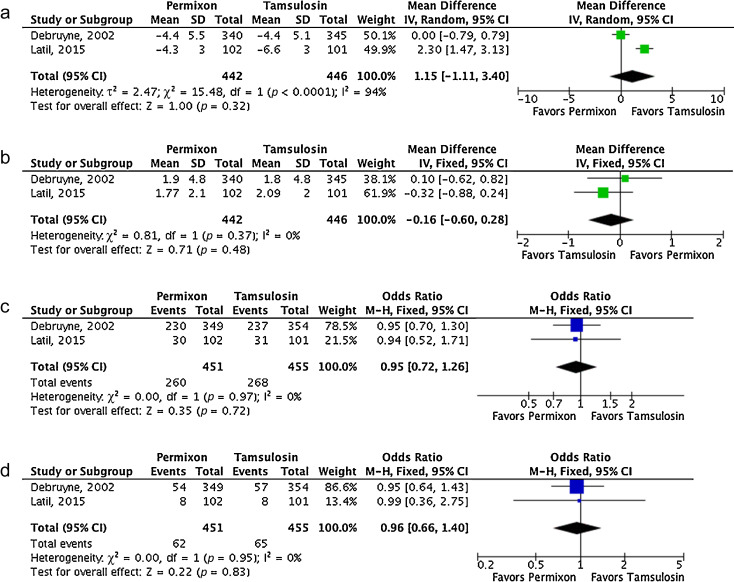

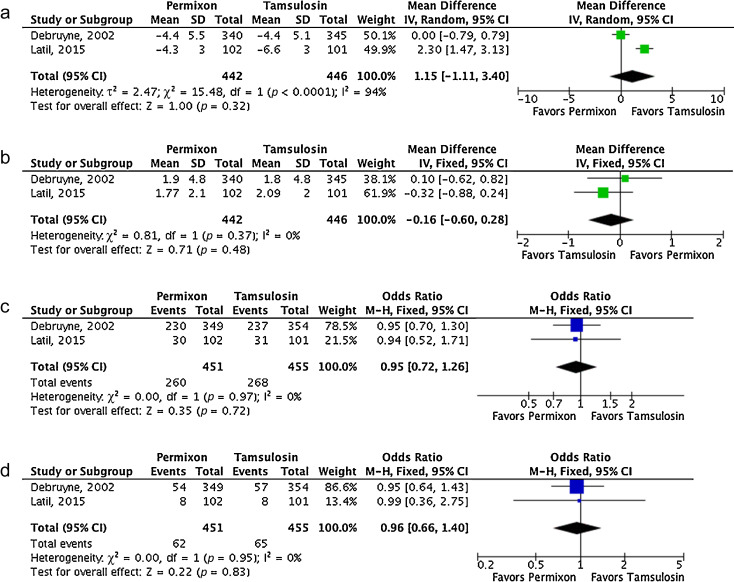

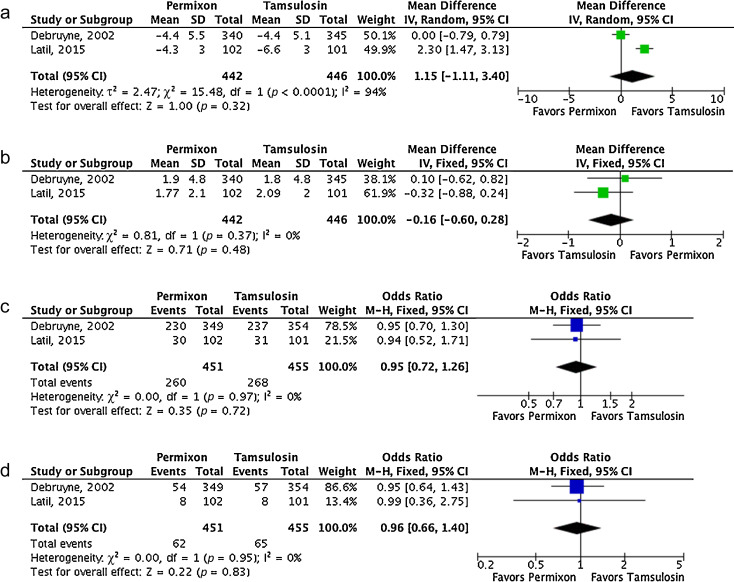

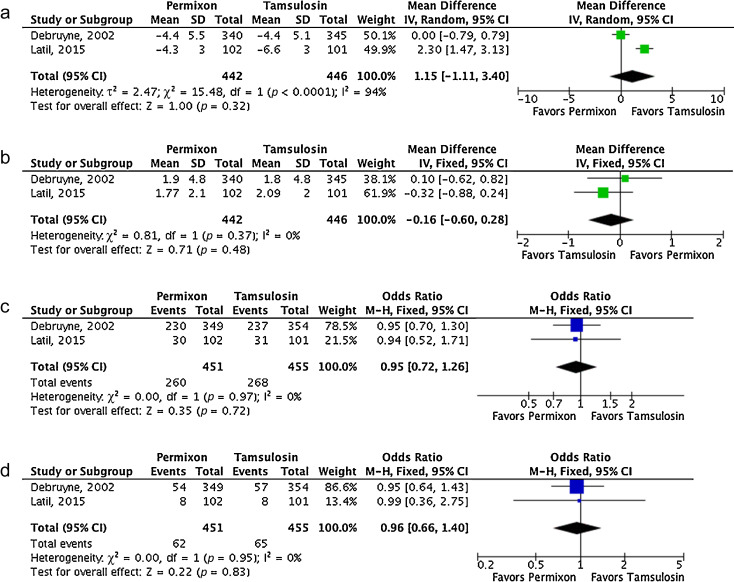

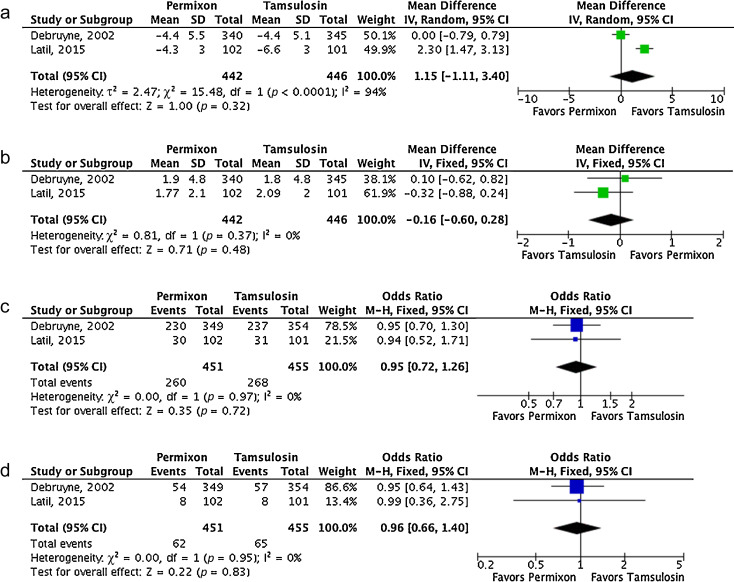

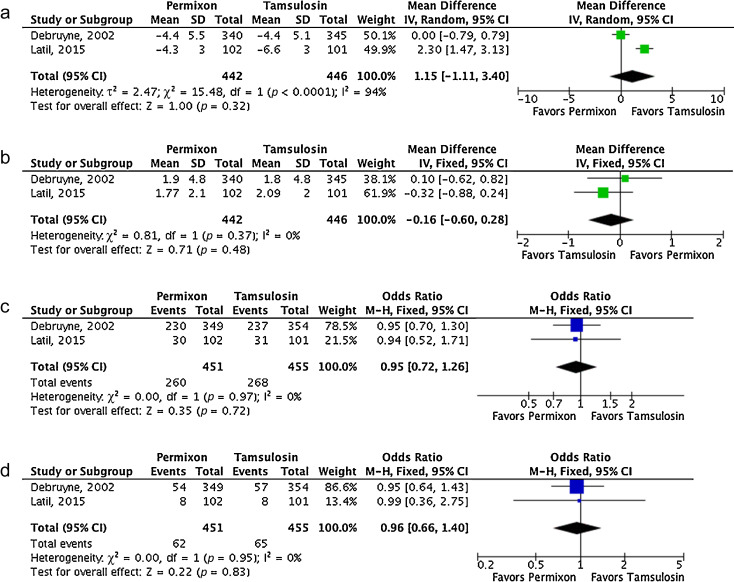

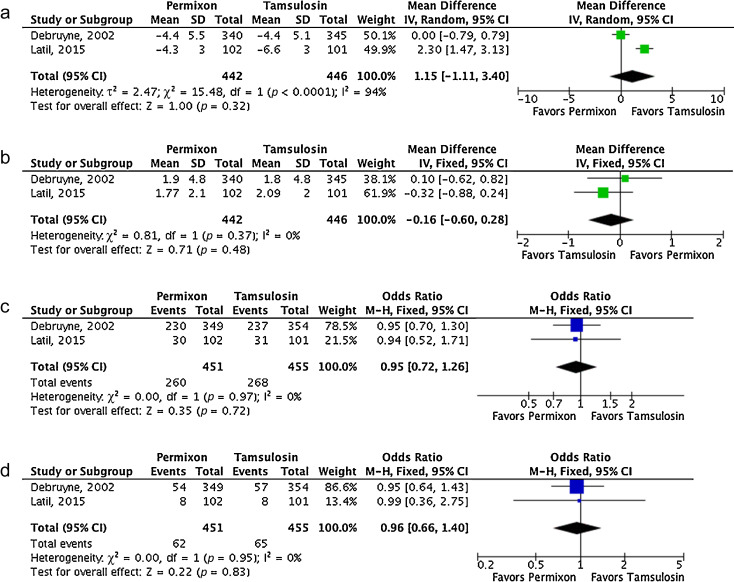

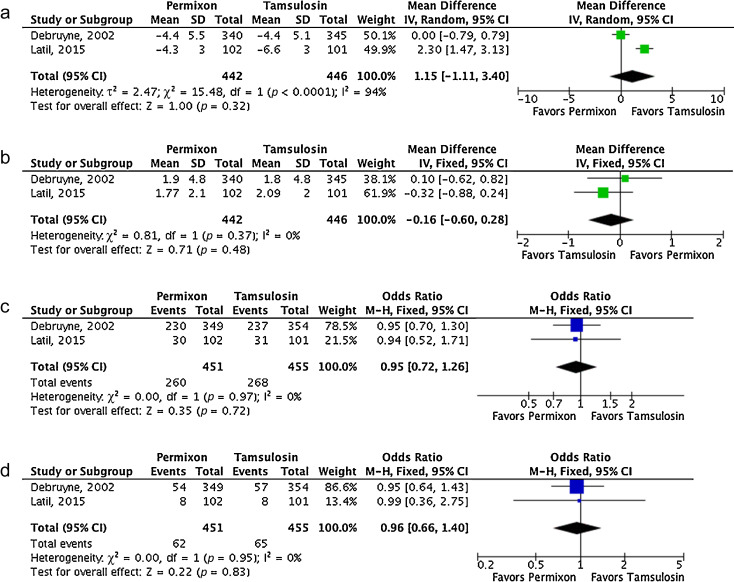

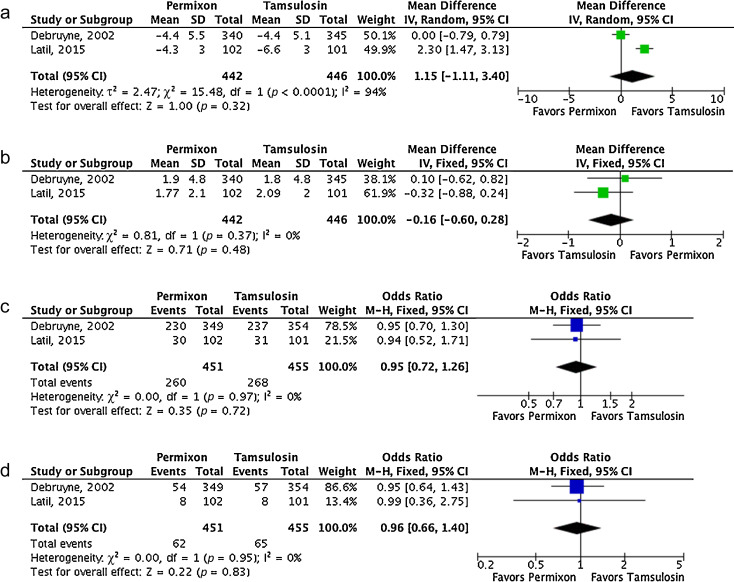

In the studies comparing Permixon with tamsulosin [22] and [23], no statistically significant difference was found in terms of mean change in IPSS from baseline to study end (WMD 1.15; 95% CI, −1.11 to 3.40; p = 0.32) and mean change in Qmax from baseline to study end (WMD −0.16; 95% CI, −0.60 to 0.28; p = 0.48) (Fig. 3a and 3b). With regard to safety, prevalence of adverse events (OR 0.95; 95% CI, 0.72–1.26; p = 0.72) and withdrawal rate (OR 0.96; 95% CI, 0.66–1.40; p = 0.83) were lower with Permixon than with tamsulosin, albeit not significantly (Fig. 3c and 3d). In one study [22], however, ejaculatory dysfunction was significantly less common with Permixon than with tamsulosin (0.5% vs 4%; p = 0.007). Figure 3 shows the forest plots for efficacy and safety data of Permixon compared with tamsulosin.

Fig. 3

Forest plots of comparisons in studies with Permixon versus tamsulosin: (a) change in International Prostate Symptom Score at study end; (b) change in maximum urinary flow rate at study end; (c) rate of overall adverse events; (d) withdrawal rate.

CI = confidence interval; IV = inverse variance; M-H = Mantel-Haenszel; SD = standard deviation.

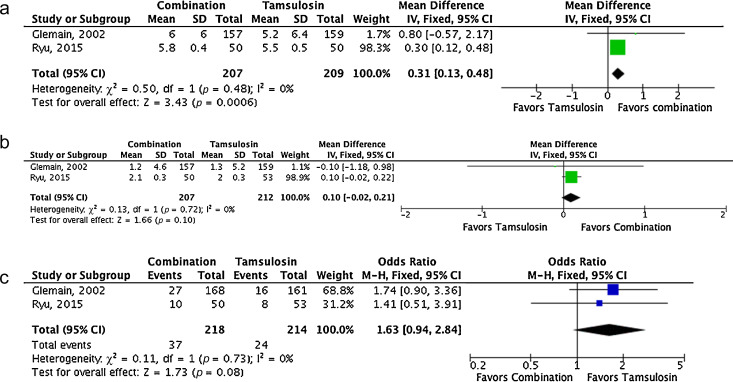

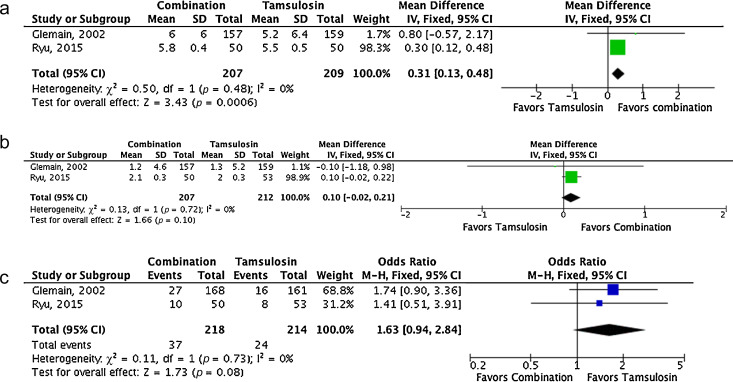

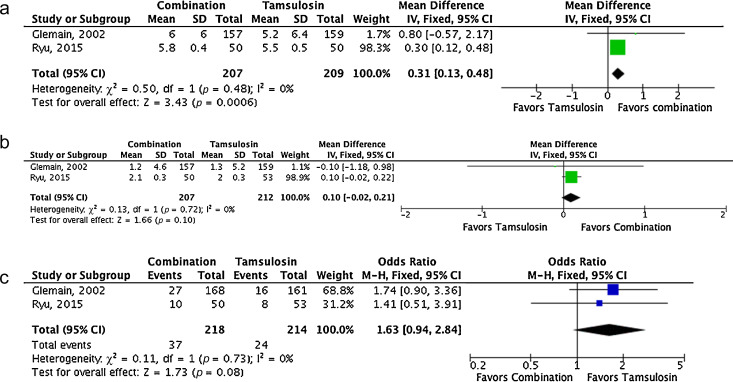

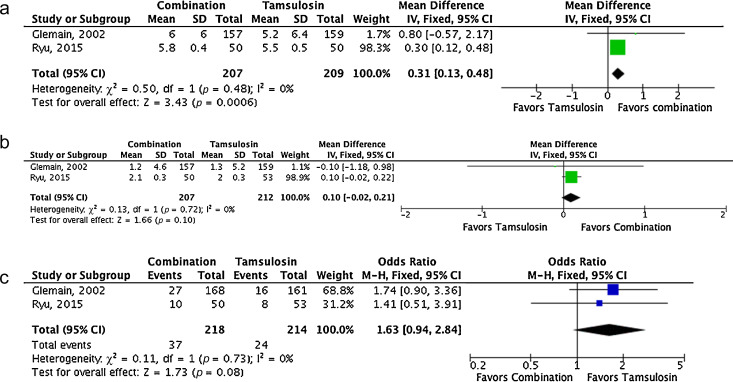

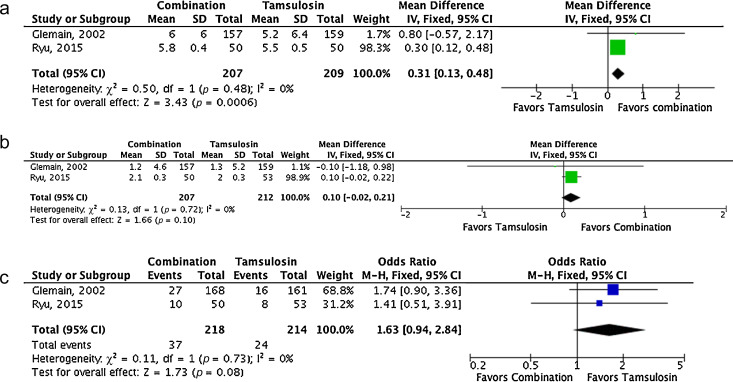

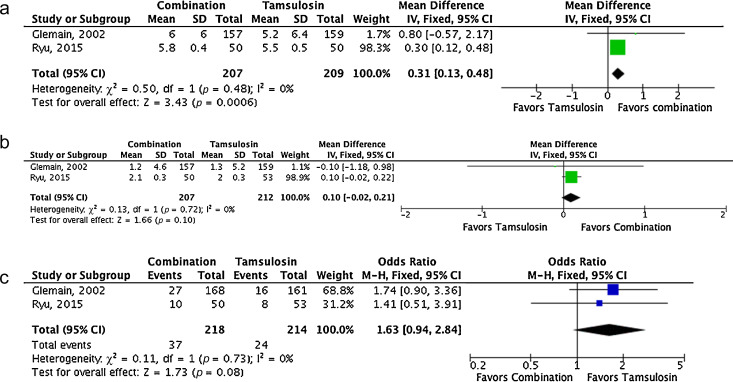

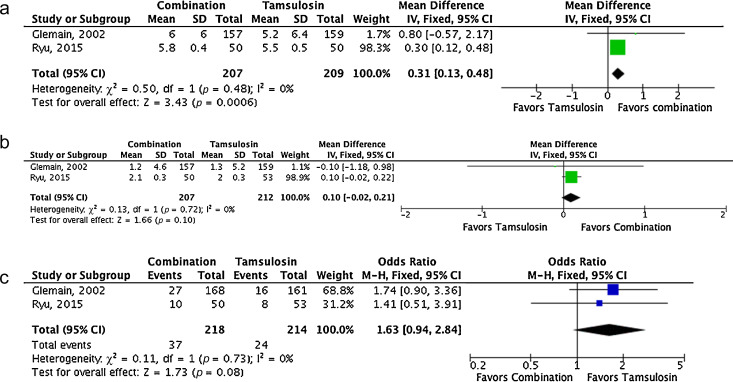

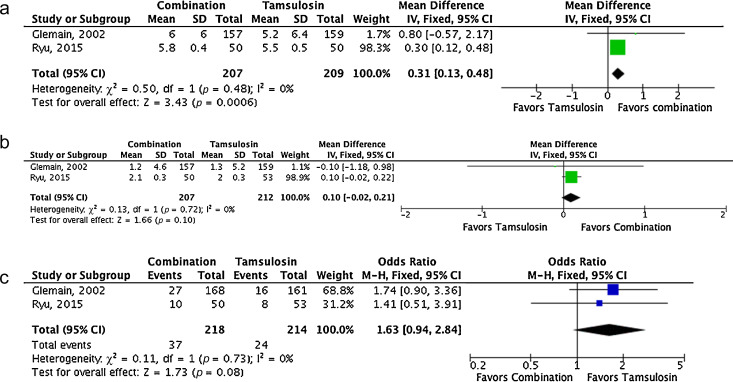

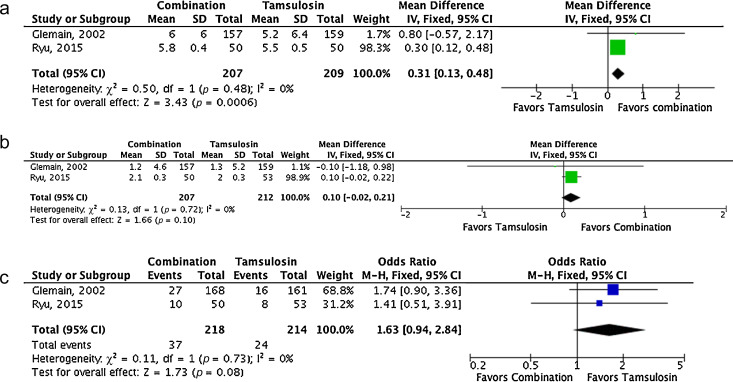

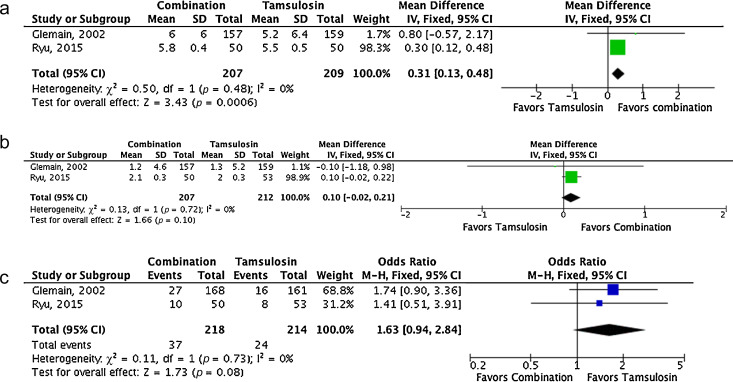

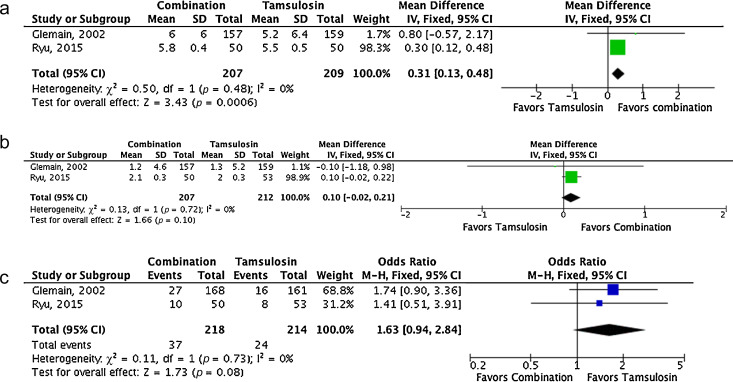

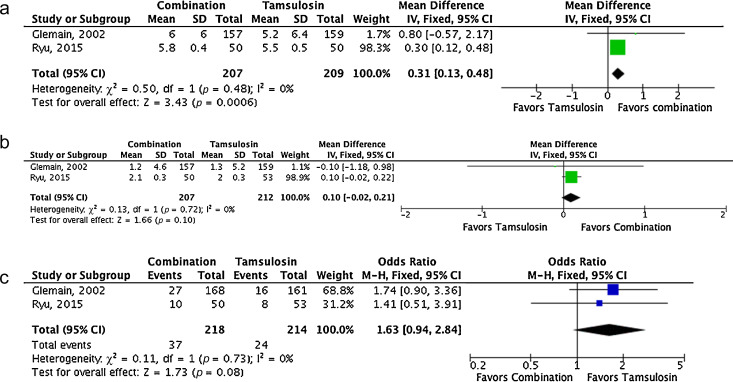

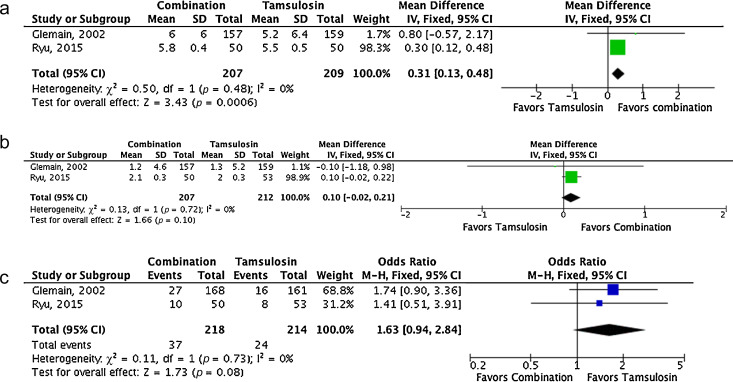

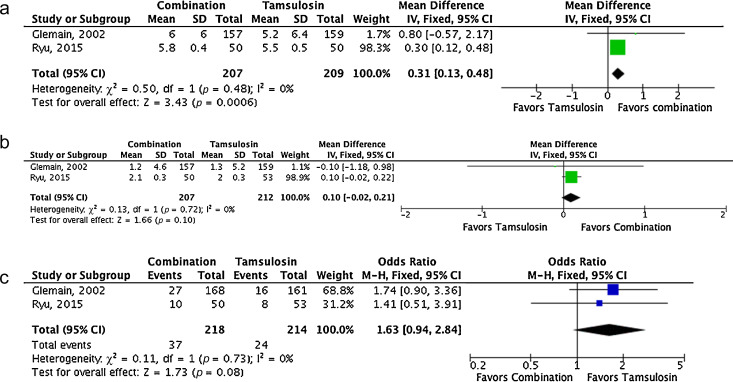

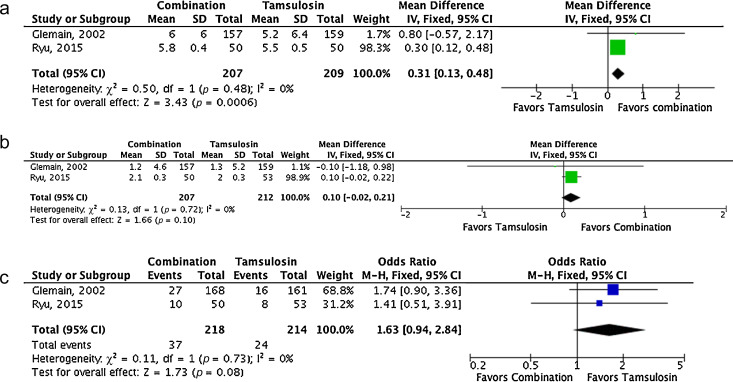

In the studies comparing Permixon plus tamsulosin with tamsulosin alone [24] and [25], mean IPSS significantly decreased from baseline to study end with the combination therapy versus tamsulosin alone (WMD 0.31; 95% CI 0.13–0.48; p < 0.01). A non–statistically significant trend in favor of the combination therapy was demonstrated for Qmax improvement (WMD 0.10; 95% CI, −0.02 to 0.21; p = 0.10). With regard to rate of adverse events, a non–statistically significant trend favoring tamsulosin monotherapy was shown (OR 1.63; 95% CI, 0.94–2.84; p = 0.08). Figure 4 shows the forest plots concerning efficacy and safety data of Permixon plus tamsulosin compared with tamsulosin.

Forest plots of comparisons in studies with combination of Permixon and tamsulosin versus tamsulosin monotherapy: (a) change in International Prostate Symptom Score at study end; (b) change in maximum urinary flow rate at study end; (c) rate of overall adverse events.

CI = confidence interval; IV = inverse variance; M-H = Mantel-Haenszel; SD = standard deviation.

A single study compared efficacy and safety of Permixon and finasteride [26]. Specifically, Carraro et al. randomized 1098 patients with moderate to severe LUTS/BPH to 26-wk treatment with Permixon (n = 553) or finasteride (n = 484). Mean prostate volume was 43 and 44 ml in the Permixon and finasteride arms, respectively. Both drugs showed similar efficacy with regard to improvement in IPSS (−5.8 with Permixon vs −6.2 with finasteride; p = 0.17) and improvement in the IPSS item for quality of life (−1.5 vs −1.4, respectively; p = 0.14), although increase in Qmax was slightly higher with finasteride (+2.7 vs +3.2, respectively; p = 0.035). However, decreased libido and impotence were less common in the Permixon arm (2.2% and 1.5%, respectively) than in the finasteride arm (3% and 2.8%, respectively). Sexual function score was significantly lower (corresponding to better function) with Permixon than with finasteride (7.9 vs 9.3; p < 0.01).

Funnel plots of all studies used in this meta-analysis were generated for all evaluated comparisons. Only a single study lies outside the 95% CI with an even distribution about the vertical, suggesting little evidence of publication bias.

α-Blockers, 5-ARIs, or their combination are among the standard drug therapies for bothersome LUTS/BPH [1] and [2]. Both categories of drugs are effective for improving symptoms, with 5-ARIs also able to reduce the risk of disease progression [1] and [2]. However, such therapies are associated with significant side effects, including postural hypotension and ejaculatory dysfunction for α-blockers and erectile dysfunction and loss of libido for 5-ARIs, that may reduce patient adherence to therapies [27] and [28]. Impairment of sexual function is of particular concern, considering that concomitant sexual dysfunction and LUTS are highly prevalent in adult men [29].

Phytotherapy is a common therapeutic option for LUTS/BPH and is used in approximately 17% of patients [3]. Specifically, Tacklind et al. reported on behalf of the Cochrane Collaboration a large meta-analysis of all RCTs evaluating Serenoa repens, which is the most common phytoterapeutic drug, and demonstrated no advantage for Serenoa repens in comparisons with placebo in relieving LUTS [7]. However, the latest version of the Cochrane meta-analysis suffers from some limitations. All of the different brands of Serenoa repens were pooled together, which is a questionable choice, as Bilia et al. clearly stated in the feedback on the Cochrane meta-analysis [7]. Specifically, some differences exist among the different brands of Serenoa repens, as reported by some preclinical studies, with Permixon seeming to be the brand with the highest percentage of free fatty acids and the highest in vitro efficacy [8], [9], and [10]. Consequently, the conclusion of the Cochrane meta-analysis might be affected by the fact that various kinds of extracts were pooled in the analysis. Indeed, this conclusion changed when the Cochrane Collaboration included in its meta-analysis well-designed RCTs but with different extracts of Serenoa repens obtained through different extraction processes [30] and [31]. Specifically, Barry et al. used Prosta-Urgenin Uno, an ethanolic Serenoa repens extract produced by Rottapharm Madaus (Selangor, Malaysia) [30], whereas Bent et al. evaluated a carbon dioxide Serenoa repens extract (Indena, Milan, Italy) [31]. That issue may explain why the Cochrane Collaboration concluded in a previous meta-analysis that Serenoa repens improves urologic symptoms and flow measures compared with placebo [32]. In fact, the same authors of the Cochrane meta-analysis stated that they did not know if their conclusions were generalizable to proprietary products of Serenoa repens such as Permixon, inviting investigation of the issue [7] and [33], which was the objective of the current meta-analysis. Moreover, some inaccuracies are evident in their data analysis and extraction. For example, Qmax values for two studies [21] and [34] reported in the Cochrane meta-analysis were not consistent with those reported in the original papers.

Consequently, to assess the validity of the Cochrane meta-analysis data for all brands of Serenoa repens with regard to Permixon, we performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of the RCTs assessing efficacy and safety of Permixon. We found that Permixon was more effective than placebo in reducing the number of nocturnal voids and Qmax and as effective as tamsulosin and short-term finasteride in improving LUTS. Moreover, combination therapy of Permixon and tamsulosin might provide some benefits in comparison to tamsulosin monotherapy in terms of LUTS improvement. In all comparisons with the other drugs, Permixon was associated with a favorable profile of adverse events, especially with regard to ejaculatory and erectile functions.

The findings of the present study were partially similar to those of Boyle et al, who reported a systematic review of RCTs and open-label studies on Permixon in 2004 [35]. Specifically, Boyle et al. demonstrated that Permixon was able to increase Qmax by roughly 2 ml/s, to reduce the mean number of nocturnal voids by roughly one, and to cause a five-point decrease in IPSS in comparison to placebo. Our analysis, which included studies comparing Permixon with tamsulosin or short-term finasteride, reconfirmed the same figures with regard to improvement in number of nocturnal voids and Qmax.

The present data showed stronger evidence for Permixon, the hexanic extract of Serenoa repens, either as monotherapy or in combination with tamsulosin, than the extract suggested by current guidelines for the whole category of phytoterapeutic drugs and for other Serenoa repens brands. This finding is supported by the recent assessment report on Serenoa repens released by the European Medicines Agency [36]. In this report, only the hexanic extract of Serenoa repens has been recognized as a well-established medicinal product thanks to its proven efficacy and tolerability in controlled trials. Conversely, ethanolic extracts have been categorized as traditional use products because of the lack of clinical trials, and supercritical CO2 extracts have not been assigned any particular status because clinical studies have not provided sufficiently reliable data and because the extracts have been marketed for <15 yr. Moreover, the anti-inflammatory properties of Serenoa repens may represent a further potential advantage of this drug to improve storage and voiding LUTS. Interestingly, this direct anti-inflammatory effect has not been demonstrated for other drugs commonly prescribed for the treatment of LUTS/BPH [6].

We acknowledge that the overall quality of the available studies was limited, with the majority of RCTs being of low methodological quality. Specifically, most studies enrolled a limited number of patients, lacked sample size calculation, and did not use validated tools to measure LUTS (eg, IPSS and frequency–volume charts). Moreover, most studies assessed short-term treatment schedules, especially regarding finasteride. High-quality RCTs comparing Permixon with placebo, α-blockers, and 5-ARIs in the long term and large clinical trials testing the anti-inflammatory properties of Permixon are needed to corroborate our findings. Furthermore, how long Permixon should be continued, who will profit most from this therapy, and whether Permixon may reduce the risk of BPH progression and related complications remain unanswered questions.

The conclusions of the recent Cochrane meta-analysis on effects and harms of Serenoa repens in the treatment of LUTS/BPH apparently do not apply to Permixon. Our meta-analysis showed that Permixon decreased the number of nocturnal voids and improved Qmax compared with placebo and had efficacy for relieving LUTS similar to that of tamsulosin and short-term finasteride. Moreover, we showed that Permixon had a favorable safety profile with a very limited impact on sexual function, which is significantly affected by all other available drugs for LUTS/BPH.

Author contributions: Vincenzo Ficarra had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Ficarra, Novara.

Acquisition of data: Novara, Giannarini.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Novara, Ficarra.

Drafting of the manuscript: Novara, Giannarini.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Alcaraz, Cózar-Olmo, Descazeaud, Montorsi, Ficarra.

Statistical analysis: Novara, Ficarra.

Obtaining funding: None.

Administrative, technical, or material support: None.

Supervision: Ficarra.

Other (specify): None.

Financial disclosures: Vincenzo Ficarra certifies that all conflicts of interest, including specific financial interests and relationships and affiliations relevant to the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript (eg, employment/affiliation, grants or funding, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, royalties, or patents filed, received, or pending), are the following: None.

Funding/Support and role of the sponsor: None.

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is a common cause of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) in adult men. α-Blockers, 5α-reductase inhibitors (5-ARIs), antimuscarinics, and phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors, either alone or in combination, are the standard medical treatments for patients with uncomplicated bothersome LUTS/BPH unresponsive to behavioral management [1] and [2].

Phytotherapy is currently prescribed in both Europe and the United States for the treatment of male LUTS/BPH, and a 2010 publication reported that approximately 17% of the patients with LUTS used this category of drug as monotherapy [3]. Moreover, a recent population study from France suggested that phytotherapy was taken by 32% of patients using combination therapies [4]. Extracts of saw palmetto, known as Serenoa repens, are the most commonly used phytotherapeutic compounds. Specifically, Serenoa repens is a lipidosterolic extract of the berry of the dwarf palm tree that has antiandrogenic action, antiproliferative proapoptotic effects, and anti-inflammatory properties [5]. This last effect could be of interest considering the most recent in vitro and in vivo studies highlighting the potential role of inflammation in LUTS/BPH [6].

A recent Cochrane Collaboration meta-analysis pooled all available randomized controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating all of the different extracts of Serenoa repens and demonstrated that they were no more effective than placebo in relieving male LUTS/BPH [7]. However, quality of plant extracts is strictly related to the quality of the botanical source as well as to the method of preparation and drug extraction. Consequently, different products derived from the same plant can have different activity and different safety profiles [8]. Some preclinical studies confirmed that major differences exist among different brands of Serenoa repens. Specifically, Habib and Wyllie [9] compared the concentrations of free fatty acids, methyl and ethyl esters, long-chain esters, and glycerides in 14 brands of Serenoa repens and demonstrated major differences among the extracts; Permixon (Pierre Fabre Medicament, Paris, France) had the highest percentage of free fatty acids considered to be responsible, at least in part, for the therapeutic effects of Serenoa repens. Moreover, Scaglione et al. [10] evaluated the efficacy of different batches of seven different Serenoa repens extracts in inhibiting 5α-reductase type I and II enzymes and demonstrated major differences among the different extracts and between different batches of the same extracts, with Permixon showing the highest efficacy and the lowest variability from batch to batch. In a recent publication by the same group [11], among nine more Serenoa repens extracts that were different from those studied previously, Permixon showed the highest activity, reinforcing the evidence that potency differs among extracts. Taken together, these data raise questions about the conclusions of the Cochrane meta-analysis because of the pooling of different, potentially nonbioequivalent extracts, as also suggested by the European Association of Urology guidelines [1].

With a focus solely on Permixon, which showed the highest efficacy in preclinical studies and has the most accurate standards of drug preparation and extraction, we performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of all RCTs assessing the efficacy and safety of Permixon for the treatment of LUTS/BPH.

The systematic review of the literature was performed in January 2016 using the Medline, Scopus, and Web of Science databases. All searches used free-text protocols searching for the keyword Serenoa repens in all record fields. No limitations were used. Moreover, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews was also searched using the same keyword.

Three authors assessed the eligibility of the papers relevant to the review topic. Specifically, all RCTs reporting on efficacy and safety from the use of Permixon in LUTS/BPH were selected. One author extracted information on patients, interventions, and outcomes that was checked by other two authors, and discrepancies were resolved by open discussion with the senior author. The quality of the retrieved RCTs was assessed using the Jadad score [12].

Meta-analysis was conducted using Review Manager software v.5.0 (Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK). Statistical heterogeneity was tested using the χ2 test. A value of p < 0.10 was used to indicate heterogeneity. Random-effects models were used for the meta-analyses. The results were expressed as weighted mean difference (WMD) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) for continuous outcomes and as an odds ratio (OR) with a 95% CI for dichotomous variables. The presence of publication bias was evaluated through a funnel plot [13].

The study complies with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement [14].

Figure 1 summarizes the literature review process that led to the identification of the 12 RCTs used in the meta-analysis. Specifically, seven RCTs compared Permixon with placebo [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], and [21], two RCTs compared Permixon with tamsulosin [22] and [23], two RCTs compared Permixon plus tamsulosin with placebo plus tamsulosin [24] and with tamsulosin alone [25], and a single RCT compared Permixon with finasteride [26]. Among these publications, there were four RCTs of good methodological quality (level of evidence 2) [22], [23], [24], and [26] and eight RCTs of poor methodological quality (level of evidence 3) [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], and [25]. Clinically speaking, all studies but three [22], [24], and [25] evaluated short-term treatment schedules; standard outcome measures, such as the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) and the American Urological Association symptom index, were used in only five studies [22], [23], [24], [25], and [26].

Table 1 summarizes the studies reporting the efficacy and safety of Permixon in comparison to placebo [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], and [21].

Table 1

Efficacy and safety data of studies comparing Permixon with placebo

| Study | Arms | Duration, wk | RCT | Nocturnal voids at study end, mean ± SD | Change in nocturnal voids from baseline, mean ± SD | Qmax, ml/s, mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Efficacy data | ||||||

| Boccafoschi and Annoscia, 1983 [15] | Permixon (n = 11) Placebo (n = 11) |

8 | Yes | 1.8 ± 2.01 2.1 ± 1.79 |

NR | 13.7 ± 7.03 12.2 ± 7.03 |

| Emili et al., 1983 [16] | Permixon (n = 15) Placebo (n = 15) |

4 | Yes | 1.67 ± 0.98 2.33 ± 1.11 |

NR | 13.7 ± 3.56 9.4 ± 2.72 |

| Mandressi et al., 1983 [17] | Permixon (n = 20) Placebo (n = 20) Pygeum (n = 20) |

4 | Yes | NR | −2.06 (−42%) −0.96 (−4%) −1.6 (−38%) |

NR |

| Cukier et al., 1985 [18] | Permixon (n = 71) Placebo (n = 76) |

10 | Yes | 2.2 ± 1.97 2.9 ± 1.99 |

NR | NR |

| Tasca et al., 1985 [19] | Permixon (n = 14) Placebo (n = 13) |

8 | Yes | 0.9 ± 2.02 1.9 ± 1.99 |

NR | 16.2 ± 7.03 11.8 ± 7.03 |

| Reece Smith et al., 1986 [20] | Permixon (n = 33) Placebo (n = 37) |

12 | Yes | 1.86 ± 1.2 1.9 ± 1.4 |

NR | NR |

| Descotes et al., 1995 [21] | Permixon (n = 82) Placebo (n = 94) |

4 | Yes | 1.4 ± 1.7 1.5 ± 1.1 |

−0.7 −0.3 |

15.3 ± 11.89 13.5 ± 8.59 |

| Safety data | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Arms | Overall drug-related adverse event, % | Libido decrease, % | Withdrawal, % | Withdrawal due to adverse events, % |

| Boccafoschi and Annoscia, 1983 [15] | Permixon (n = 11) Placebo (n = 11) |

0 10 |

NR | 0 0 |

0 0 |

| Emili et al., 1983 [16] | Permixon (n = 15) Placebo (n = 15) |

0 0 |

NR | 0 0 |

0 0 |

| Tasca et al., 1985 [19] | Permixon (n = 15) Placebo (n = 15) |

6.7 15 |

NR | 6.7 13.3 |

6.7 0 |

| Reece Smith et al., 1986 [20] | Permixon (n = 40) Placebo (n = 40) |

10 0 |

0 0 |

17 7 |

5 0 |

NR = not reported; Qmax = maximum urinary flow rate; RCT = randomized controlled trial; SD = standard deviation.

The number of nocturnal voids at study end were significantly lower with Permixon (WMD −0.31; 95% CI, −0.59 to −0.03; p = 0.03). Moreover, maximum urinary flow rate (Qmax) at study end was significantly higher in the patients treated with Permixon (WMD 3.37; 95% CI, 1.71–5.03; p < 0.0001). With regard to safety, the overall adverse event rates were similar for Permixon and placebo (OR 1.12; 95% CI, 0.13–9.75; p = 0.92). Finally, withdrawal rates were similar following Permixon or placebo (OR 1.52; 95% CI, 0.32–7.33; p = 0.60).

Figure 2 shows the forest plots for efficacy and safety data of Permixon in comparison to placebo.

Forest plots of comparisons in studies with Permixon versus placebo: (a) number of nocturnal voids at study end; (b) maximum urinary flow rate at study end; (c) rate of overall adverse events; (d) withdrawal rate.

CI = confidence interval; IV = inverse variance; M-H = Mantel-Haenszel; SD = standard deviation.

Table 2 summarizes the studies reporting efficacy and safety of Permixon or combination therapy compared with tamsulosin.

Table 2

Efficacy and safety data of studies comparing Permixon or combination therapy with tamsulosin

| Study | Arms | Duration, wk | RCT | Change in IPSS from baseline, mean ± SD | Change in IPSS storage subscore, mean ± SD | Change in IPSS voiding subscore, mean ± SD | Change in IPSS QoL score, mean ± SD | Nocturnal voids, mean ± SD | Qmax increase, ml/s, mean ± SD | PVR, ml, mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Efficacy data | ||||||||||

| Debruyne et al., 2002 [22] | Permixon (n = 340) Tamsulosin (n = 345) |

52 | Yes | −4.4 ± 5.5 −4.4 ± 5.1 |

−1.7 ± 2.8 −1.5 ± 2.4 |

−2.8 ± 3.7 −2.9 ± 3.7 |

NR | NR | 1.9 ± 4.8 1.8 ± 4.8 |

NR |

| Latil et al., 2015 [23] | Permixon (n = 102) Tamsulosin (n = 101) |

12 | Yes | −4.3 ± 3 −6.6 ± 3 |

NR | NR | −0.87 ± 1.6 −1.29 ± 1.6 |

NR | 1.77 ± 2.1 2.09 ± 2 |

15.2 ± 33.6 4.04 ± 34 |

| Glémain et al., 2002 [24] | Permixon plus tamsulosin (n = 157) Placebo plus tamsulosin (n = 159) |

52 | Yes | −6.0 ± 6 −5.2 ± 6.4 |

−1.9 ± 2.9 −1.9 ± 3.1 |

−4.1 ± 4.4 −3.3 ± 4.6 |

−1.3 ± 1.4 −1.0 ± 1.4 |

NR | 1.2 ± 4.6 1.3 ± 5.2 |

NR |

| Ryu et al., 2015 [25] | Permixon plus tamsulosin (n = 60) Tamsulosin (n = 60) |

52 | Yes | −5.8 ± 0.43 −5.5 ± 0.54 |

−1.9 ± 0.33 0.9 ± 0.3 |

−3.9 ± 0.41 −4.5 ± 0.42 |

−2.4 ± 0.43 −2.5 ± 0.4 |

NR | 2.1 ± 0.31 2.0 ± 0.26 |

8.3 ± 1.45 −10.6 ± 1.79 |

| Safety data | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Arms | Overall AEs, % | Withdrawal, % | Withdrawal due to AEs, % | Ejaculatory dysfunction, % | Postural hypotension, % | Headache, % | Dizziness, % |

| Debruyne et al., 2002 [22] | Permixon (n = 349) Tamsulosin (n = 354) |

66* 67* |

15 16 |

8 8 |

0.5 4 |

1 1 |

8 11 |

3 2 |

| Latil et al., 2015 [23] | Permixon (n = 102) Tamsulosin (n = 101) |

29 31 |

8 3 |

NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Glémain et al., 2002 [24] | Permixon plus tamsulosin (n = 168) Placebo plus tamsulosin (n = 161) |

16 10 |

18 20 |

4 3 |

8 5 |

1 0 |

NR | 2 2 |

| Ryu et al., 2015 [25] | Permixon plus tamsulosin (n = 60) Tamsulosin (n = 60) |

20 17 |

0 0 |

0 0 |

6 7 |

4 4 |

10 11 |

4 2 |

* These figures include both drug-related and drug-unrelated AEs.

AE = adverse event; IPSS = International Prostate Symptom Score; NR = not reported; PVR = postvoid residual urine; Qmax = maximum urinary flow rate; QoL = quality of life; RCT = randomized controlled trial; SD = standard deviation.

In the studies comparing Permixon with tamsulosin [22] and [23], no statistically significant difference was found in terms of mean change in IPSS from baseline to study end (WMD 1.15; 95% CI, −1.11 to 3.40; p = 0.32) and mean change in Qmax from baseline to study end (WMD −0.16; 95% CI, −0.60 to 0.28; p = 0.48) (Fig. 3a and 3b). With regard to safety, prevalence of adverse events (OR 0.95; 95% CI, 0.72–1.26; p = 0.72) and withdrawal rate (OR 0.96; 95% CI, 0.66–1.40; p = 0.83) were lower with Permixon than with tamsulosin, albeit not significantly (Fig. 3c and 3d). In one study [22], however, ejaculatory dysfunction was significantly less common with Permixon than with tamsulosin (0.5% vs 4%; p = 0.007). Figure 3 shows the forest plots for efficacy and safety data of Permixon compared with tamsulosin.

Fig. 3

Forest plots of comparisons in studies with Permixon versus tamsulosin: (a) change in International Prostate Symptom Score at study end; (b) change in maximum urinary flow rate at study end; (c) rate of overall adverse events; (d) withdrawal rate.

CI = confidence interval; IV = inverse variance; M-H = Mantel-Haenszel; SD = standard deviation.

In the studies comparing Permixon plus tamsulosin with tamsulosin alone [24] and [25], mean IPSS significantly decreased from baseline to study end with the combination therapy versus tamsulosin alone (WMD 0.31; 95% CI 0.13–0.48; p < 0.01). A non–statistically significant trend in favor of the combination therapy was demonstrated for Qmax improvement (WMD 0.10; 95% CI, −0.02 to 0.21; p = 0.10). With regard to rate of adverse events, a non–statistically significant trend favoring tamsulosin monotherapy was shown (OR 1.63; 95% CI, 0.94–2.84; p = 0.08). Figure 4 shows the forest plots concerning efficacy and safety data of Permixon plus tamsulosin compared with tamsulosin.

Forest plots of comparisons in studies with combination of Permixon and tamsulosin versus tamsulosin monotherapy: (a) change in International Prostate Symptom Score at study end; (b) change in maximum urinary flow rate at study end; (c) rate of overall adverse events.

CI = confidence interval; IV = inverse variance; M-H = Mantel-Haenszel; SD = standard deviation.

A single study compared efficacy and safety of Permixon and finasteride [26]. Specifically, Carraro et al. randomized 1098 patients with moderate to severe LUTS/BPH to 26-wk treatment with Permixon (n = 553) or finasteride (n = 484). Mean prostate volume was 43 and 44 ml in the Permixon and finasteride arms, respectively. Both drugs showed similar efficacy with regard to improvement in IPSS (−5.8 with Permixon vs −6.2 with finasteride; p = 0.17) and improvement in the IPSS item for quality of life (−1.5 vs −1.4, respectively; p = 0.14), although increase in Qmax was slightly higher with finasteride (+2.7 vs +3.2, respectively; p = 0.035). However, decreased libido and impotence were less common in the Permixon arm (2.2% and 1.5%, respectively) than in the finasteride arm (3% and 2.8%, respectively). Sexual function score was significantly lower (corresponding to better function) with Permixon than with finasteride (7.9 vs 9.3; p < 0.01).

Funnel plots of all studies used in this meta-analysis were generated for all evaluated comparisons. Only a single study lies outside the 95% CI with an even distribution about the vertical, suggesting little evidence of publication bias.

α-Blockers, 5-ARIs, or their combination are among the standard drug therapies for bothersome LUTS/BPH [1] and [2]. Both categories of drugs are effective for improving symptoms, with 5-ARIs also able to reduce the risk of disease progression [1] and [2]. However, such therapies are associated with significant side effects, including postural hypotension and ejaculatory dysfunction for α-blockers and erectile dysfunction and loss of libido for 5-ARIs, that may reduce patient adherence to therapies [27] and [28]. Impairment of sexual function is of particular concern, considering that concomitant sexual dysfunction and LUTS are highly prevalent in adult men [29].

Phytotherapy is a common therapeutic option for LUTS/BPH and is used in approximately 17% of patients [3]. Specifically, Tacklind et al. reported on behalf of the Cochrane Collaboration a large meta-analysis of all RCTs evaluating Serenoa repens, which is the most common phytoterapeutic drug, and demonstrated no advantage for Serenoa repens in comparisons with placebo in relieving LUTS [7]. However, the latest version of the Cochrane meta-analysis suffers from some limitations. All of the different brands of Serenoa repens were pooled together, which is a questionable choice, as Bilia et al. clearly stated in the feedback on the Cochrane meta-analysis [7]. Specifically, some differences exist among the different brands of Serenoa repens, as reported by some preclinical studies, with Permixon seeming to be the brand with the highest percentage of free fatty acids and the highest in vitro efficacy [8], [9], and [10]. Consequently, the conclusion of the Cochrane meta-analysis might be affected by the fact that various kinds of extracts were pooled in the analysis. Indeed, this conclusion changed when the Cochrane Collaboration included in its meta-analysis well-designed RCTs but with different extracts of Serenoa repens obtained through different extraction processes [30] and [31]. Specifically, Barry et al. used Prosta-Urgenin Uno, an ethanolic Serenoa repens extract produced by Rottapharm Madaus (Selangor, Malaysia) [30], whereas Bent et al. evaluated a carbon dioxide Serenoa repens extract (Indena, Milan, Italy) [31]. That issue may explain why the Cochrane Collaboration concluded in a previous meta-analysis that Serenoa repens improves urologic symptoms and flow measures compared with placebo [32]. In fact, the same authors of the Cochrane meta-analysis stated that they did not know if their conclusions were generalizable to proprietary products of Serenoa repens such as Permixon, inviting investigation of the issue [7] and [33], which was the objective of the current meta-analysis. Moreover, some inaccuracies are evident in their data analysis and extraction. For example, Qmax values for two studies [21] and [34] reported in the Cochrane meta-analysis were not consistent with those reported in the original papers.

Consequently, to assess the validity of the Cochrane meta-analysis data for all brands of Serenoa repens with regard to Permixon, we performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of the RCTs assessing efficacy and safety of Permixon. We found that Permixon was more effective than placebo in reducing the number of nocturnal voids and Qmax and as effective as tamsulosin and short-term finasteride in improving LUTS. Moreover, combination therapy of Permixon and tamsulosin might provide some benefits in comparison to tamsulosin monotherapy in terms of LUTS improvement. In all comparisons with the other drugs, Permixon was associated with a favorable profile of adverse events, especially with regard to ejaculatory and erectile functions.

The findings of the present study were partially similar to those of Boyle et al, who reported a systematic review of RCTs and open-label studies on Permixon in 2004 [35]. Specifically, Boyle et al. demonstrated that Permixon was able to increase Qmax by roughly 2 ml/s, to reduce the mean number of nocturnal voids by roughly one, and to cause a five-point decrease in IPSS in comparison to placebo. Our analysis, which included studies comparing Permixon with tamsulosin or short-term finasteride, reconfirmed the same figures with regard to improvement in number of nocturnal voids and Qmax.

The present data showed stronger evidence for Permixon, the hexanic extract of Serenoa repens, either as monotherapy or in combination with tamsulosin, than the extract suggested by current guidelines for the whole category of phytoterapeutic drugs and for other Serenoa repens brands. This finding is supported by the recent assessment report on Serenoa repens released by the European Medicines Agency [36]. In this report, only the hexanic extract of Serenoa repens has been recognized as a well-established medicinal product thanks to its proven efficacy and tolerability in controlled trials. Conversely, ethanolic extracts have been categorized as traditional use products because of the lack of clinical trials, and supercritical CO2 extracts have not been assigned any particular status because clinical studies have not provided sufficiently reliable data and because the extracts have been marketed for <15 yr. Moreover, the anti-inflammatory properties of Serenoa repens may represent a further potential advantage of this drug to improve storage and voiding LUTS. Interestingly, this direct anti-inflammatory effect has not been demonstrated for other drugs commonly prescribed for the treatment of LUTS/BPH [6].

We acknowledge that the overall quality of the available studies was limited, with the majority of RCTs being of low methodological quality. Specifically, most studies enrolled a limited number of patients, lacked sample size calculation, and did not use validated tools to measure LUTS (eg, IPSS and frequency–volume charts). Moreover, most studies assessed short-term treatment schedules, especially regarding finasteride. High-quality RCTs comparing Permixon with placebo, α-blockers, and 5-ARIs in the long term and large clinical trials testing the anti-inflammatory properties of Permixon are needed to corroborate our findings. Furthermore, how long Permixon should be continued, who will profit most from this therapy, and whether Permixon may reduce the risk of BPH progression and related complications remain unanswered questions.

The conclusions of the recent Cochrane meta-analysis on effects and harms of Serenoa repens in the treatment of LUTS/BPH apparently do not apply to Permixon. Our meta-analysis showed that Permixon decreased the number of nocturnal voids and improved Qmax compared with placebo and had efficacy for relieving LUTS similar to that of tamsulosin and short-term finasteride. Moreover, we showed that Permixon had a favorable safety profile with a very limited impact on sexual function, which is significantly affected by all other available drugs for LUTS/BPH.

Author contributions: Vincenzo Ficarra had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Ficarra, Novara.

Acquisition of data: Novara, Giannarini.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Novara, Ficarra.

Drafting of the manuscript: Novara, Giannarini.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Alcaraz, Cózar-Olmo, Descazeaud, Montorsi, Ficarra.

Statistical analysis: Novara, Ficarra.

Obtaining funding: None.

Administrative, technical, or material support: None.

Supervision: Ficarra.

Other (specify): None.

Financial disclosures: Vincenzo Ficarra certifies that all conflicts of interest, including specific financial interests and relationships and affiliations relevant to the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript (eg, employment/affiliation, grants or funding, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, royalties, or patents filed, received, or pending), are the following: None.

Funding/Support and role of the sponsor: None.

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is a common cause of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) in adult men. α-Blockers, 5α-reductase inhibitors (5-ARIs), antimuscarinics, and phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors, either alone or in combination, are the standard medical treatments for patients with uncomplicated bothersome LUTS/BPH unresponsive to behavioral management [1] and [2].

Phytotherapy is currently prescribed in both Europe and the United States for the treatment of male LUTS/BPH, and a 2010 publication reported that approximately 17% of the patients with LUTS used this category of drug as monotherapy [3]. Moreover, a recent population study from France suggested that phytotherapy was taken by 32% of patients using combination therapies [4]. Extracts of saw palmetto, known as Serenoa repens, are the most commonly used phytotherapeutic compounds. Specifically, Serenoa repens is a lipidosterolic extract of the berry of the dwarf palm tree that has antiandrogenic action, antiproliferative proapoptotic effects, and anti-inflammatory properties [5]. This last effect could be of interest considering the most recent in vitro and in vivo studies highlighting the potential role of inflammation in LUTS/BPH [6].

A recent Cochrane Collaboration meta-analysis pooled all available randomized controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating all of the different extracts of Serenoa repens and demonstrated that they were no more effective than placebo in relieving male LUTS/BPH [7]. However, quality of plant extracts is strictly related to the quality of the botanical source as well as to the method of preparation and drug extraction. Consequently, different products derived from the same plant can have different activity and different safety profiles [8]. Some preclinical studies confirmed that major differences exist among different brands of Serenoa repens. Specifically, Habib and Wyllie [9] compared the concentrations of free fatty acids, methyl and ethyl esters, long-chain esters, and glycerides in 14 brands of Serenoa repens and demonstrated major differences among the extracts; Permixon (Pierre Fabre Medicament, Paris, France) had the highest percentage of free fatty acids considered to be responsible, at least in part, for the therapeutic effects of Serenoa repens. Moreover, Scaglione et al. [10] evaluated the efficacy of different batches of seven different Serenoa repens extracts in inhibiting 5α-reductase type I and II enzymes and demonstrated major differences among the different extracts and between different batches of the same extracts, with Permixon showing the highest efficacy and the lowest variability from batch to batch. In a recent publication by the same group [11], among nine more Serenoa repens extracts that were different from those studied previously, Permixon showed the highest activity, reinforcing the evidence that potency differs among extracts. Taken together, these data raise questions about the conclusions of the Cochrane meta-analysis because of the pooling of different, potentially nonbioequivalent extracts, as also suggested by the European Association of Urology guidelines [1].

With a focus solely on Permixon, which showed the highest efficacy in preclinical studies and has the most accurate standards of drug preparation and extraction, we performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of all RCTs assessing the efficacy and safety of Permixon for the treatment of LUTS/BPH.

The systematic review of the literature was performed in January 2016 using the Medline, Scopus, and Web of Science databases. All searches used free-text protocols searching for the keyword Serenoa repens in all record fields. No limitations were used. Moreover, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews was also searched using the same keyword.

Three authors assessed the eligibility of the papers relevant to the review topic. Specifically, all RCTs reporting on efficacy and safety from the use of Permixon in LUTS/BPH were selected. One author extracted information on patients, interventions, and outcomes that was checked by other two authors, and discrepancies were resolved by open discussion with the senior author. The quality of the retrieved RCTs was assessed using the Jadad score [12].

Meta-analysis was conducted using Review Manager software v.5.0 (Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK). Statistical heterogeneity was tested using the χ2 test. A value of p < 0.10 was used to indicate heterogeneity. Random-effects models were used for the meta-analyses. The results were expressed as weighted mean difference (WMD) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) for continuous outcomes and as an odds ratio (OR) with a 95% CI for dichotomous variables. The presence of publication bias was evaluated through a funnel plot [13].

The study complies with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement [14].

Figure 1 summarizes the literature review process that led to the identification of the 12 RCTs used in the meta-analysis. Specifically, seven RCTs compared Permixon with placebo [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], and [21], two RCTs compared Permixon with tamsulosin [22] and [23], two RCTs compared Permixon plus tamsulosin with placebo plus tamsulosin [24] and with tamsulosin alone [25], and a single RCT compared Permixon with finasteride [26]. Among these publications, there were four RCTs of good methodological quality (level of evidence 2) [22], [23], [24], and [26] and eight RCTs of poor methodological quality (level of evidence 3) [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], and [25]. Clinically speaking, all studies but three [22], [24], and [25] evaluated short-term treatment schedules; standard outcome measures, such as the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) and the American Urological Association symptom index, were used in only five studies [22], [23], [24], [25], and [26].

Table 1 summarizes the studies reporting the efficacy and safety of Permixon in comparison to placebo [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], and [21].

Table 1

Efficacy and safety data of studies comparing Permixon with placebo

| Study | Arms | Duration, wk | RCT | Nocturnal voids at study end, mean ± SD | Change in nocturnal voids from baseline, mean ± SD | Qmax, ml/s, mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Efficacy data | ||||||

| Boccafoschi and Annoscia, 1983 [15] | Permixon (n = 11) Placebo (n = 11) |

8 | Yes | 1.8 ± 2.01 2.1 ± 1.79 |

NR | 13.7 ± 7.03 12.2 ± 7.03 |

| Emili et al., 1983 [16] | Permixon (n = 15) Placebo (n = 15) |

4 | Yes | 1.67 ± 0.98 2.33 ± 1.11 |

NR | 13.7 ± 3.56 9.4 ± 2.72 |

| Mandressi et al., 1983 [17] | Permixon (n = 20) Placebo (n = 20) Pygeum (n = 20) |

4 | Yes | NR | −2.06 (−42%) −0.96 (−4%) −1.6 (−38%) |

NR |

| Cukier et al., 1985 [18] | Permixon (n = 71) Placebo (n = 76) |

10 | Yes | 2.2 ± 1.97 2.9 ± 1.99 |

NR | NR |

| Tasca et al., 1985 [19] | Permixon (n = 14) Placebo (n = 13) |

8 | Yes | 0.9 ± 2.02 1.9 ± 1.99 |

NR | 16.2 ± 7.03 11.8 ± 7.03 |

| Reece Smith et al., 1986 [20] | Permixon (n = 33) Placebo (n = 37) |

12 | Yes | 1.86 ± 1.2 1.9 ± 1.4 |

NR | NR |

| Descotes et al., 1995 [21] | Permixon (n = 82) Placebo (n = 94) |

4 | Yes | 1.4 ± 1.7 1.5 ± 1.1 |

−0.7 −0.3 |

15.3 ± 11.89 13.5 ± 8.59 |

| Safety data | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Arms | Overall drug-related adverse event, % | Libido decrease, % | Withdrawal, % | Withdrawal due to adverse events, % |

| Boccafoschi and Annoscia, 1983 [15] | Permixon (n = 11) Placebo (n = 11) |

0 10 |

NR | 0 0 |

0 0 |

| Emili et al., 1983 [16] | Permixon (n = 15) Placebo (n = 15) |

0 0 |

NR | 0 0 |

0 0 |

| Tasca et al., 1985 [19] | Permixon (n = 15) Placebo (n = 15) |

6.7 15 |

NR | 6.7 13.3 |

6.7 0 |

| Reece Smith et al., 1986 [20] | Permixon (n = 40) Placebo (n = 40) |

10 0 |

0 0 |

17 7 |

5 0 |

NR = not reported; Qmax = maximum urinary flow rate; RCT = randomized controlled trial; SD = standard deviation.

The number of nocturnal voids at study end were significantly lower with Permixon (WMD −0.31; 95% CI, −0.59 to −0.03; p = 0.03). Moreover, maximum urinary flow rate (Qmax) at study end was significantly higher in the patients treated with Permixon (WMD 3.37; 95% CI, 1.71–5.03; p < 0.0001). With regard to safety, the overall adverse event rates were similar for Permixon and placebo (OR 1.12; 95% CI, 0.13–9.75; p = 0.92). Finally, withdrawal rates were similar following Permixon or placebo (OR 1.52; 95% CI, 0.32–7.33; p = 0.60).

Figure 2 shows the forest plots for efficacy and safety data of Permixon in comparison to placebo.

Forest plots of comparisons in studies with Permixon versus placebo: (a) number of nocturnal voids at study end; (b) maximum urinary flow rate at study end; (c) rate of overall adverse events; (d) withdrawal rate.

CI = confidence interval; IV = inverse variance; M-H = Mantel-Haenszel; SD = standard deviation.

Table 2 summarizes the studies reporting efficacy and safety of Permixon or combination therapy compared with tamsulosin.

Table 2

Efficacy and safety data of studies comparing Permixon or combination therapy with tamsulosin

| Study | Arms | Duration, wk | RCT | Change in IPSS from baseline, mean ± SD | Change in IPSS storage subscore, mean ± SD | Change in IPSS voiding subscore, mean ± SD | Change in IPSS QoL score, mean ± SD | Nocturnal voids, mean ± SD | Qmax increase, ml/s, mean ± SD | PVR, ml, mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Efficacy data | ||||||||||

| Debruyne et al., 2002 [22] | Permixon (n = 340) Tamsulosin (n = 345) |

52 | Yes | −4.4 ± 5.5 −4.4 ± 5.1 |

−1.7 ± 2.8 −1.5 ± 2.4 |

−2.8 ± 3.7 −2.9 ± 3.7 |

NR | NR | 1.9 ± 4.8 1.8 ± 4.8 |

NR |

| Latil et al., 2015 [23] | Permixon (n = 102) Tamsulosin (n = 101) |

12 | Yes | −4.3 ± 3 −6.6 ± 3 |

NR | NR | −0.87 ± 1.6 −1.29 ± 1.6 |

NR | 1.77 ± 2.1 2.09 ± 2 |

15.2 ± 33.6 4.04 ± 34 |

| Glémain et al., 2002 [24] | Permixon plus tamsulosin (n = 157) Placebo plus tamsulosin (n = 159) |

52 | Yes | −6.0 ± 6 −5.2 ± 6.4 |

−1.9 ± 2.9 −1.9 ± 3.1 |

−4.1 ± 4.4 −3.3 ± 4.6 |

−1.3 ± 1.4 −1.0 ± 1.4 |

NR | 1.2 ± 4.6 1.3 ± 5.2 |

NR |

| Ryu et al., 2015 [25] | Permixon plus tamsulosin (n = 60) Tamsulosin (n = 60) |

52 | Yes | −5.8 ± 0.43 −5.5 ± 0.54 |

−1.9 ± 0.33 0.9 ± 0.3 |

−3.9 ± 0.41 −4.5 ± 0.42 |

−2.4 ± 0.43 −2.5 ± 0.4 |

NR | 2.1 ± 0.31 2.0 ± 0.26 |

8.3 ± 1.45 −10.6 ± 1.79 |

| Safety data | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Arms | Overall AEs, % | Withdrawal, % | Withdrawal due to AEs, % | Ejaculatory dysfunction, % | Postural hypotension, % | Headache, % | Dizziness, % |

| Debruyne et al., 2002 [22] | Permixon (n = 349) Tamsulosin (n = 354) |

66* 67* |

15 16 |

8 8 |

0.5 4 |

1 1 |

8 11 |

3 2 |

| Latil et al., 2015 [23] | Permixon (n = 102) Tamsulosin (n = 101) |

29 31 |

8 3 |

NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Glémain et al., 2002 [24] | Permixon plus tamsulosin (n = 168) Placebo plus tamsulosin (n = 161) |

16 10 |

18 20 |

4 3 |

8 5 |

1 0 |

NR | 2 2 |

| Ryu et al., 2015 [25] | Permixon plus tamsulosin (n = 60) Tamsulosin (n = 60) |

20 17 |

0 0 |

0 0 |

6 7 |

4 4 |

10 11 |

4 2 |

* These figures include both drug-related and drug-unrelated AEs.

AE = adverse event; IPSS = International Prostate Symptom Score; NR = not reported; PVR = postvoid residual urine; Qmax = maximum urinary flow rate; QoL = quality of life; RCT = randomized controlled trial; SD = standard deviation.

In the studies comparing Permixon with tamsulosin [22] and [23], no statistically significant difference was found in terms of mean change in IPSS from baseline to study end (WMD 1.15; 95% CI, −1.11 to 3.40; p = 0.32) and mean change in Qmax from baseline to study end (WMD −0.16; 95% CI, −0.60 to 0.28; p = 0.48) (Fig. 3a and 3b). With regard to safety, prevalence of adverse events (OR 0.95; 95% CI, 0.72–1.26; p = 0.72) and withdrawal rate (OR 0.96; 95% CI, 0.66–1.40; p = 0.83) were lower with Permixon than with tamsulosin, albeit not significantly (Fig. 3c and 3d). In one study [22], however, ejaculatory dysfunction was significantly less common with Permixon than with tamsulosin (0.5% vs 4%; p = 0.007). Figure 3 shows the forest plots for efficacy and safety data of Permixon compared with tamsulosin.

Fig. 3

Forest plots of comparisons in studies with Permixon versus tamsulosin: (a) change in International Prostate Symptom Score at study end; (b) change in maximum urinary flow rate at study end; (c) rate of overall adverse events; (d) withdrawal rate.

CI = confidence interval; IV = inverse variance; M-H = Mantel-Haenszel; SD = standard deviation.

In the studies comparing Permixon plus tamsulosin with tamsulosin alone [24] and [25], mean IPSS significantly decreased from baseline to study end with the combination therapy versus tamsulosin alone (WMD 0.31; 95% CI 0.13–0.48; p < 0.01). A non–statistically significant trend in favor of the combination therapy was demonstrated for Qmax improvement (WMD 0.10; 95% CI, −0.02 to 0.21; p = 0.10). With regard to rate of adverse events, a non–statistically significant trend favoring tamsulosin monotherapy was shown (OR 1.63; 95% CI, 0.94–2.84; p = 0.08). Figure 4 shows the forest plots concerning efficacy and safety data of Permixon plus tamsulosin compared with tamsulosin.

Forest plots of comparisons in studies with combination of Permixon and tamsulosin versus tamsulosin monotherapy: (a) change in International Prostate Symptom Score at study end; (b) change in maximum urinary flow rate at study end; (c) rate of overall adverse events.

CI = confidence interval; IV = inverse variance; M-H = Mantel-Haenszel; SD = standard deviation.

A single study compared efficacy and safety of Permixon and finasteride [26]. Specifically, Carraro et al. randomized 1098 patients with moderate to severe LUTS/BPH to 26-wk treatment with Permixon (n = 553) or finasteride (n = 484). Mean prostate volume was 43 and 44 ml in the Permixon and finasteride arms, respectively. Both drugs showed similar efficacy with regard to improvement in IPSS (−5.8 with Permixon vs −6.2 with finasteride; p = 0.17) and improvement in the IPSS item for quality of life (−1.5 vs −1.4, respectively; p = 0.14), although increase in Qmax was slightly higher with finasteride (+2.7 vs +3.2, respectively; p = 0.035). However, decreased libido and impotence were less common in the Permixon arm (2.2% and 1.5%, respectively) than in the finasteride arm (3% and 2.8%, respectively). Sexual function score was significantly lower (corresponding to better function) with Permixon than with finasteride (7.9 vs 9.3; p < 0.01).

Funnel plots of all studies used in this meta-analysis were generated for all evaluated comparisons. Only a single study lies outside the 95% CI with an even distribution about the vertical, suggesting little evidence of publication bias.

α-Blockers, 5-ARIs, or their combination are among the standard drug therapies for bothersome LUTS/BPH [1] and [2]. Both categories of drugs are effective for improving symptoms, with 5-ARIs also able to reduce the risk of disease progression [1] and [2]. However, such therapies are associated with significant side effects, including postural hypotension and ejaculatory dysfunction for α-blockers and erectile dysfunction and loss of libido for 5-ARIs, that may reduce patient adherence to therapies [27] and [28]. Impairment of sexual function is of particular concern, considering that concomitant sexual dysfunction and LUTS are highly prevalent in adult men [29].

Phytotherapy is a common therapeutic option for LUTS/BPH and is used in approximately 17% of patients [3]. Specifically, Tacklind et al. reported on behalf of the Cochrane Collaboration a large meta-analysis of all RCTs evaluating Serenoa repens, which is the most common phytoterapeutic drug, and demonstrated no advantage for Serenoa repens in comparisons with placebo in relieving LUTS [7]. However, the latest version of the Cochrane meta-analysis suffers from some limitations. All of the different brands of Serenoa repens were pooled together, which is a questionable choice, as Bilia et al. clearly stated in the feedback on the Cochrane meta-analysis [7]. Specifically, some differences exist among the different brands of Serenoa repens, as reported by some preclinical studies, with Permixon seeming to be the brand with the highest percentage of free fatty acids and the highest in vitro efficacy [8], [9], and [10]. Consequently, the conclusion of the Cochrane meta-analysis might be affected by the fact that various kinds of extracts were pooled in the analysis. Indeed, this conclusion changed when the Cochrane Collaboration included in its meta-analysis well-designed RCTs but with different extracts of Serenoa repens obtained through different extraction processes [30] and [31]. Specifically, Barry et al. used Prosta-Urgenin Uno, an ethanolic Serenoa repens extract produced by Rottapharm Madaus (Selangor, Malaysia) [30], whereas Bent et al. evaluated a carbon dioxide Serenoa repens extract (Indena, Milan, Italy) [31]. That issue may explain why the Cochrane Collaboration concluded in a previous meta-analysis that Serenoa repens improves urologic symptoms and flow measures compared with placebo [32]. In fact, the same authors of the Cochrane meta-analysis stated that they did not know if their conclusions were generalizable to proprietary products of Serenoa repens such as Permixon, inviting investigation of the issue [7] and [33], which was the objective of the current meta-analysis. Moreover, some inaccuracies are evident in their data analysis and extraction. For example, Qmax values for two studies [21] and [34] reported in the Cochrane meta-analysis were not consistent with those reported in the original papers.

Consequently, to assess the validity of the Cochrane meta-analysis data for all brands of Serenoa repens with regard to Permixon, we performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of the RCTs assessing efficacy and safety of Permixon. We found that Permixon was more effective than placebo in reducing the number of nocturnal voids and Qmax and as effective as tamsulosin and short-term finasteride in improving LUTS. Moreover, combination therapy of Permixon and tamsulosin might provide some benefits in comparison to tamsulosin monotherapy in terms of LUTS improvement. In all comparisons with the other drugs, Permixon was associated with a favorable profile of adverse events, especially with regard to ejaculatory and erectile functions.

The findings of the present study were partially similar to those of Boyle et al, who reported a systematic review of RCTs and open-label studies on Permixon in 2004 [35]. Specifically, Boyle et al. demonstrated that Permixon was able to increase Qmax by roughly 2 ml/s, to reduce the mean number of nocturnal voids by roughly one, and to cause a five-point decrease in IPSS in comparison to placebo. Our analysis, which included studies comparing Permixon with tamsulosin or short-term finasteride, reconfirmed the same figures with regard to improvement in number of nocturnal voids and Qmax.

The present data showed stronger evidence for Permixon, the hexanic extract of Serenoa repens, either as monotherapy or in combination with tamsulosin, than the extract suggested by current guidelines for the whole category of phytoterapeutic drugs and for other Serenoa repens brands. This finding is supported by the recent assessment report on Serenoa repens released by the European Medicines Agency [36]. In this report, only the hexanic extract of Serenoa repens has been recognized as a well-established medicinal product thanks to its proven efficacy and tolerability in controlled trials. Conversely, ethanolic extracts have been categorized as traditional use products because of the lack of clinical trials, and supercritical CO2 extracts have not been assigned any particular status because clinical studies have not provided sufficiently reliable data and because the extracts have been marketed for <15 yr. Moreover, the anti-inflammatory properties of Serenoa repens may represent a further potential advantage of this drug to improve storage and voiding LUTS. Interestingly, this direct anti-inflammatory effect has not been demonstrated for other drugs commonly prescribed for the treatment of LUTS/BPH [6].

We acknowledge that the overall quality of the available studies was limited, with the majority of RCTs being of low methodological quality. Specifically, most studies enrolled a limited number of patients, lacked sample size calculation, and did not use validated tools to measure LUTS (eg, IPSS and frequency–volume charts). Moreover, most studies assessed short-term treatment schedules, especially regarding finasteride. High-quality RCTs comparing Permixon with placebo, α-blockers, and 5-ARIs in the long term and large clinical trials testing the anti-inflammatory properties of Permixon are needed to corroborate our findings. Furthermore, how long Permixon should be continued, who will profit most from this therapy, and whether Permixon may reduce the risk of BPH progression and related complications remain unanswered questions.

The conclusions of the recent Cochrane meta-analysis on effects and harms of Serenoa repens in the treatment of LUTS/BPH apparently do not apply to Permixon. Our meta-analysis showed that Permixon decreased the number of nocturnal voids and improved Qmax compared with placebo and had efficacy for relieving LUTS similar to that of tamsulosin and short-term finasteride. Moreover, we showed that Permixon had a favorable safety profile with a very limited impact on sexual function, which is significantly affected by all other available drugs for LUTS/BPH.

Author contributions: Vincenzo Ficarra had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Ficarra, Novara.

Acquisition of data: Novara, Giannarini.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Novara, Ficarra.

Drafting of the manuscript: Novara, Giannarini.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Alcaraz, Cózar-Olmo, Descazeaud, Montorsi, Ficarra.

Statistical analysis: Novara, Ficarra.

Obtaining funding: None.

Administrative, technical, or material support: None.

Supervision: Ficarra.

Other (specify): None.

Financial disclosures: Vincenzo Ficarra certifies that all conflicts of interest, including specific financial interests and relationships and affiliations relevant to the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript (eg, employment/affiliation, grants or funding, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, royalties, or patents filed, received, or pending), are the following: None.

Funding/Support and role of the sponsor: None.

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is a common cause of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) in adult men. α-Blockers, 5α-reductase inhibitors (5-ARIs), antimuscarinics, and phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors, either alone or in combination, are the standard medical treatments for patients with uncomplicated bothersome LUTS/BPH unresponsive to behavioral management [1] and [2].

Phytotherapy is currently prescribed in both Europe and the United States for the treatment of male LUTS/BPH, and a 2010 publication reported that approximately 17% of the patients with LUTS used this category of drug as monotherapy [3]. Moreover, a recent population study from France suggested that phytotherapy was taken by 32% of patients using combination therapies [4]. Extracts of saw palmetto, known as Serenoa repens, are the most commonly used phytotherapeutic compounds. Specifically, Serenoa repens is a lipidosterolic extract of the berry of the dwarf palm tree that has antiandrogenic action, antiproliferative proapoptotic effects, and anti-inflammatory properties [5]. This last effect could be of interest considering the most recent in vitro and in vivo studies highlighting the potential role of inflammation in LUTS/BPH [6].

A recent Cochrane Collaboration meta-analysis pooled all available randomized controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating all of the different extracts of Serenoa repens and demonstrated that they were no more effective than placebo in relieving male LUTS/BPH [7]. However, quality of plant extracts is strictly related to the quality of the botanical source as well as to the method of preparation and drug extraction. Consequently, different products derived from the same plant can have different activity and different safety profiles [8]. Some preclinical studies confirmed that major differences exist among different brands of Serenoa repens. Specifically, Habib and Wyllie [9] compared the concentrations of free fatty acids, methyl and ethyl esters, long-chain esters, and glycerides in 14 brands of Serenoa repens and demonstrated major differences among the extracts; Permixon (Pierre Fabre Medicament, Paris, France) had the highest percentage of free fatty acids considered to be responsible, at least in part, for the therapeutic effects of Serenoa repens. Moreover, Scaglione et al. [10] evaluated the efficacy of different batches of seven different Serenoa repens extracts in inhibiting 5α-reductase type I and II enzymes and demonstrated major differences among the different extracts and between different batches of the same extracts, with Permixon showing the highest efficacy and the lowest variability from batch to batch. In a recent publication by the same group [11], among nine more Serenoa repens extracts that were different from those studied previously, Permixon showed the highest activity, reinforcing the evidence that potency differs among extracts. Taken together, these data raise questions about the conclusions of the Cochrane meta-analysis because of the pooling of different, potentially nonbioequivalent extracts, as also suggested by the European Association of Urology guidelines [1].

With a focus solely on Permixon, which showed the highest efficacy in preclinical studies and has the most accurate standards of drug preparation and extraction, we performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of all RCTs assessing the efficacy and safety of Permixon for the treatment of LUTS/BPH.

The systematic review of the literature was performed in January 2016 using the Medline, Scopus, and Web of Science databases. All searches used free-text protocols searching for the keyword Serenoa repens in all record fields. No limitations were used. Moreover, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews was also searched using the same keyword.

Three authors assessed the eligibility of the papers relevant to the review topic. Specifically, all RCTs reporting on efficacy and safety from the use of Permixon in LUTS/BPH were selected. One author extracted information on patients, interventions, and outcomes that was checked by other two authors, and discrepancies were resolved by open discussion with the senior author. The quality of the retrieved RCTs was assessed using the Jadad score [12].

Meta-analysis was conducted using Review Manager software v.5.0 (Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK). Statistical heterogeneity was tested using the χ2 test. A value of p < 0.10 was used to indicate heterogeneity. Random-effects models were used for the meta-analyses. The results were expressed as weighted mean difference (WMD) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) for continuous outcomes and as an odds ratio (OR) with a 95% CI for dichotomous variables. The presence of publication bias was evaluated through a funnel plot [13].

The study complies with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement [14].