Context

The treatment of nocturia is a key challenge due to the multi-factorial pathophysiology of the symptom and the disparate outcome measures used in research.

Objective

To assess and compare available therapy options for nocturia, in terms of symptom severity and quality of life.

Evidence acquisition

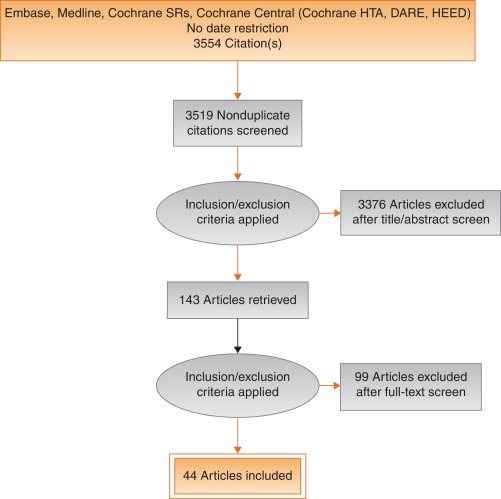

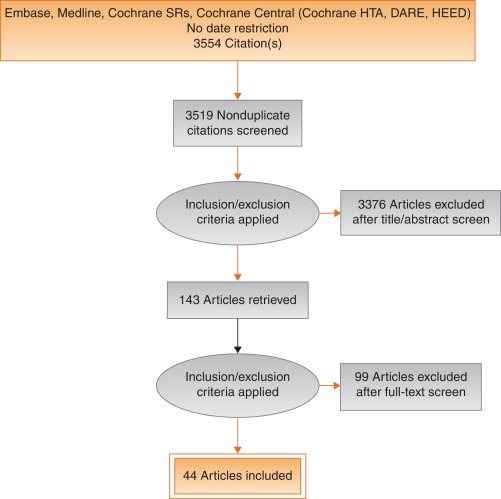

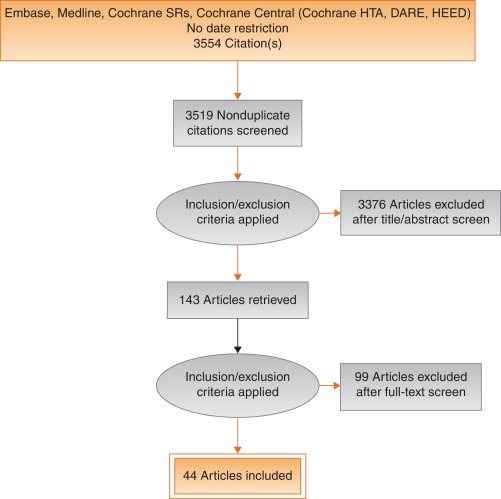

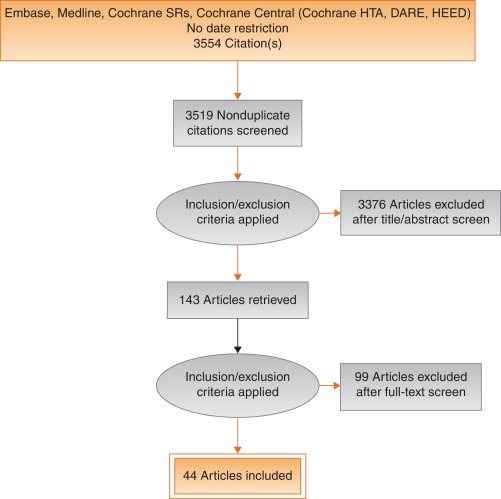

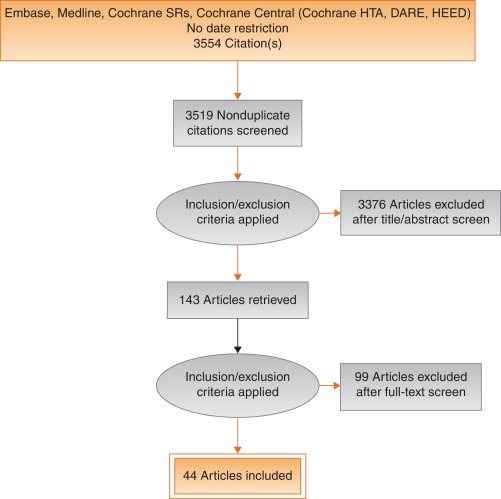

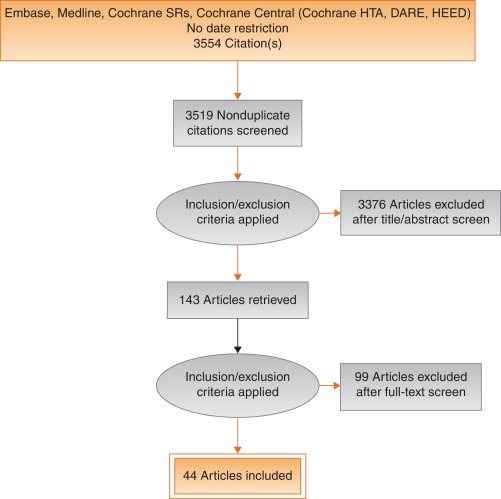

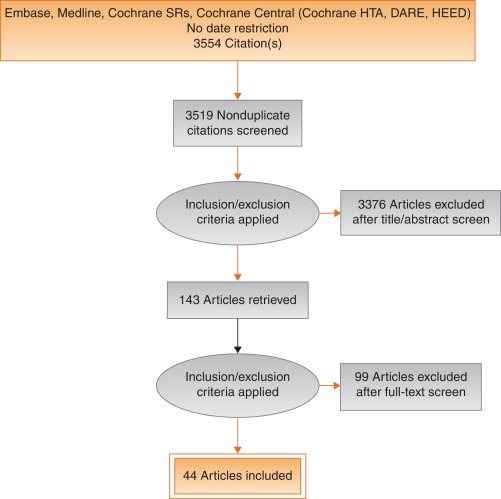

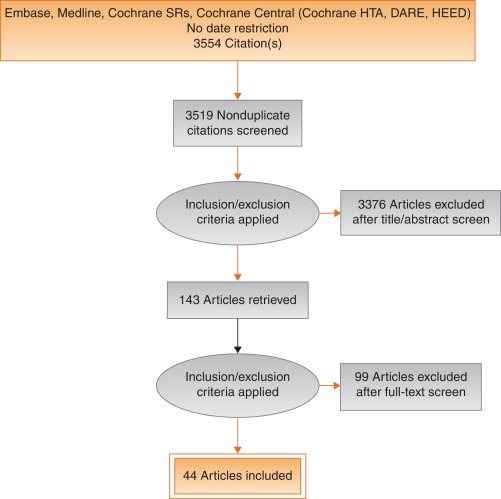

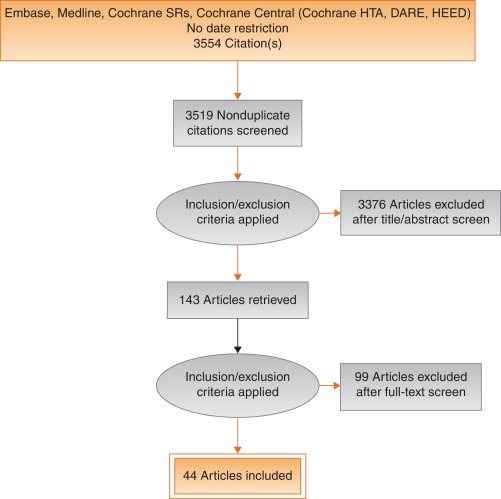

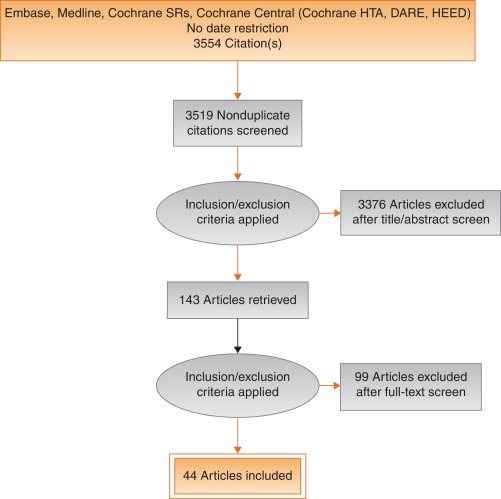

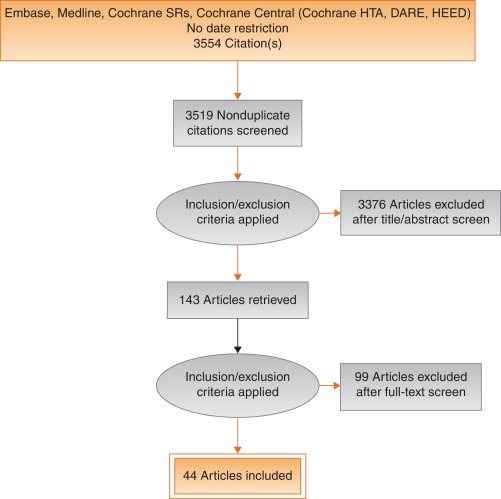

Medical databases (Embase, Medline, Cochrane Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Central) were searched with no date restriction. Comparative studies were included which studied adult men with nocturia as the primary presentation and lower urinary tract symptoms including nocturia or nocturnal polyuria. Outcomes were symptom severity, quality of life, and harms.

Evidence synthesis

We identified 44 articles. Antidiuretic therapy using dose titration was more effective than placebo in relation to nocturnal voiding frequency and duration of undisturbed sleep; baseline serum sodium is a key selection criterion. Screening for hyponatremia (< 130 mmol/l) must be undertaken at baseline, after initiation or dose titration, and during treatment. Medications to treat lower urinary tract dysfunction (α-1 adrenergic antagonists, 5-α reductase inhibitors, phosphodiesterase type 5inhibitor, antimuscarinics, beta-3 agonist, and phytotherapy) were generally not significantly better than placebo in short-term use. Benefits with combination therapies were not consistently observed. Other medications (diuretics, agents to promote sleep, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories) were sometimes associated with response or quality of life improvement. The recommendations of the Guideline Panel are presented.

Conclusions

Issues of trial design make therapy of nocturia a challenging topic. The range of contributory factors relevant in nocturia makes it desirable to identify predictors of response to guide therapy. Consistent responses were reported for titrated antidiuretic therapy. For other therapies, responses were less certain, and potentially of limited clinical benefit.

Patient summary

This review provides an overview of the current drug treatments of nocturia, which is the need to wake at night to pass urine. The symptom can be caused by several different medical conditions, and measuring its severity and impact varies in separate research studies. No single treatment deals with the symptom in all contexts, and careful assessment is essential to make suitable treatment selection.

Nocturia is defined by the International Continence Society (ICS) as the complaint that an individual has to wake at night one or more times to void [1] . It reflects the relationship between the amount of urine produced while asleep, and the storage by the bladder of urine received. Nocturia can occur as part of lower urinary tract dysfunction (LUTD), notably in overactive bladder syndrome (OAB). Nocturia can also occur in association with other forms of LUTD, such as bladder outlet obstruction or chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Nocturia is a feature of systemic conditions affecting water and salt balance [2] , leading to excessive production of urine at all times (global polyuria) or primarily at night (nocturnal polyuria), so that nocturia can be a systemic symptom [3 4] . For example, cardiovascular, endocrine, and renal disease can affect water and salt homeostasis [5] , leading to increased rate of urine production.

Summarizing the causative categories for nocturia, the International Consultation on Male Lower Urinary Tract symptoms (LUTS) [6] listed:

Bladder storage problems;

24-h (global) polyuria (> 40 ml/kg urine output over a 24-h period);

Nocturnal polyuria (nocturnal output exceeding 20% of 24-h urine output in younger patients, or 33% of urine output in people aged over 65 yr [1] );

Sleep disorders;

Mixed etiology.

Thus, the treatment of nocturia is potentially complex, and was identified by the European Association of Urology Guidelines Panel for Male non-neurogenic LUTS as a key challenge. The aim of the current systematic review of treatment was to assess and compare available therapy options for nocturia, in terms of symptom severity and quality of life. The review focusses on men, in view of the differing lower urinary tract anatomy and medication options available compared with women.

The objectives were to determine the relative benefits and harms of treatment options for nocturia, and to perform subgroup and/or sensitivity analysis.

The Embase, Medline, Cochrane Systematic Reviews, and Cochrane Central (Cochrane Health Technology Assessment, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, Health Economics Evaluations Database) were searched with no restriction on date of publication (date of final search September 2016). The search strategy was registered on PROSPERO on October 21, 2015 ( http://dx.doi.org/10.15124/CRD42015027092 ). Comparative studies were included (randomized controlled trials [RCTs], and nonrandomized comparative studies [both prospective and retrospective, interventional, or observational]), studying adult men (male-only or mixed sex populations), with nocturia or nocturnal polyuria as a primary outcome, categorized within the following symptom groups:

Nocturia (ICS definition [7] , or as defined by trialist) as the primary presentation (ie, nocturia as the predominant bothersome symptom);

Nocturia as a secondary component of LUTS (ie, LUTS including nocturia);

Nocturnal polyuria (ICS definition [7] , or alternative definition if stated by the investigating group).

Interventions included: anticholinergics, mirabegron, α-blockers, 5-α reductase inhibitors, oral phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors, desmopressin, diuretics, sleep-promoting agents, and phytotherapy. Comparator controls were: no treatment, placebo, and alternative experimental treatment.

The primary outcomes were:

Symptom severity for nocturia (outcome measure defined as < 2 episodes, or cure [ie, no episodes of nocturia] or reduction in nocturia episodes, or as defined by trialist);

Quality of life for nocturia.

The secondary outcomes were:

Harms: adverse events of treatment and events leading to potential harm (eg, hyponatremia, voiding difficulties), withdrawal, or drop-out rates;

Any other outcomes judged relevant by reviewer.

Two review authors independently screened the titles and abstracts of identified records, and the full text of potentially eligible records was evaluated using a standardized form. Risk of bias was assessed, including: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other sources of bias. A list of potential confounders was developed a priori: age, sex, description of primary pathology, severity, or bother of nocturia.

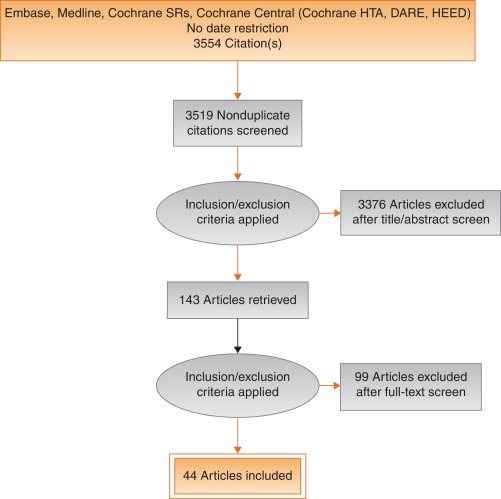

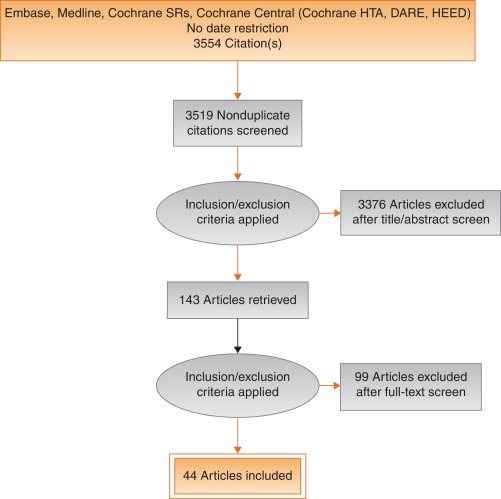

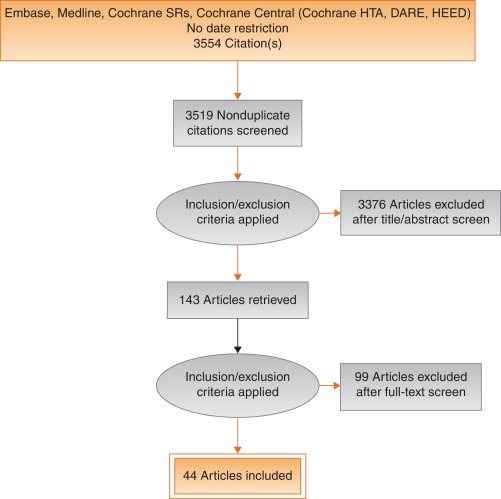

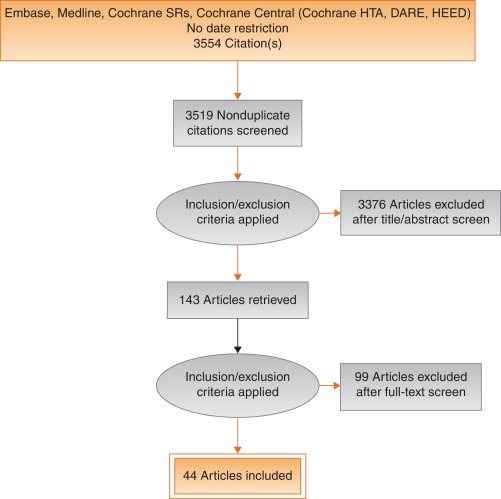

Studies are summarized in Figure 1 .

Fig. 1

Systematic review flow chart.

DARE = Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects; HEED = Health Economic Evaluations Database; HTA = Health Technology Assessment; SR = systemic reviews.

One study investigated a behavioral modification program with desmopressin in comparison with desmopressin monotherapy in patients with nocturnal polyuria and nocturia (≥ 2 voids/night; Levels of Evidence [LoE] 1b) [8] . Nocturnal voids declined by –1.5 with combined therapy, compared with –1.2 on desmopressin alone (not significant). Another group randomized obese men with LUTS already on tamsulosin to receive a basic or a comprehensive weight reduction program (LoE 2b) [9] . The improvement in nocturia episodes was similar in both arms (–0.1 ± 0.9). Both studies showed mild adverse events only in pharmacotherapy-related arms.

The antidiuretic hormone arginine vasopressin increases renal water reabsorption and urinary osmolality. Antidiuretic therapy using the arginine vasopressin V2 receptor agonist desmopressin, with dose titration to achieve the best clinical response (as defined by the researchers in each study; including the dose to achieve either no voids per night, a decrease in nocturnal urine production of ≥ 20%, or nocturnal diuresis < 0.5 ml/min), was more effective than placebo in terms of reduced nocturnal voiding frequency ( Table 1 ) and duration of undisturbed sleep ( Table 2 ).

| Desmopressin | Placebo | Mean difference | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study or subgroup | Mean | SD | Total | Mean | SD | Total | Weight (%) | IV, fixed, 95% CI | |

| Asplung 1999 | –0.8 | 0.99 | 17 | –0.2 | 1.1 | 17 | 15.4 | –0.60 (-1.30, 0.1)] |  |

| Fu 2011 | –1.5 | 1.28 | 39 | –0.3 | 1.41 | 41 | 21.9 | –1.20 (-1.79, –0.61) | |

| Mattiasson 2002 | –1.3 | 1.25 | 81 | –0.5 | 1.75 | 62 | 28.8 | –0.80 (-1.31, –0.29) | |

| Rezakhanina 2011 a | –1 | 0 | 30 | –0.2 | 0 | 30 | Not estimable | ||

| Van Kerrebroeck 2007 | –1.25 | 1.35 | 59 | –0.4 | 1.29 | 61 | 34.4 | –0.85 (1.32, –0.38) | |

| Wang 2011 b | –1.5 | 0 | 57 | –0.8 | 0 | 58 | Not estimable | ||

| Total (95% CI) | 283 | 269 | 100 | –0.87 (–1.15, –0.60) | |||||

| Heterogeneity: χ 2 = 1.85, df = 3 ( p = 0.60); I 2 = 0% | |||||||||

| Test for overall effect: Z = 6.21 ( p < 0.00001) | |||||||||

a No standard deviation values.

b No standard deviation values.

CI = confidence interval; df = difference; SD = standard deviation.Table 1Effect of desmopressin (with dose titrated against response) on nocturnal voiding frequency

| Desmopressin | Placebo | Mean difference | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study or subgroup | Mean | SD | Total | Mean | SD | Total | Weight (%) | IV, fixed, 95% CI | |

| Asplung 1999 a | 102 | 0 | 17 | 18 | 0 | 17 | Not estimable |  |

|

| Fu 2011 | 69.6 | 52.798 | 39 | 23.7 | 50.434 | 41 | 50.9 | 45.90 (23.25, 68.55) | |

| Mattiasson 2002 | 110.4 | 102.71 | 81 | 24 | 84.483 | 62 | 27.7 | 86.40 (55.70, 117.10) | |

| Rezakhanina 2011 b | 120 | 0 | 30 | 30 | 0 | 30 | Not estimable | ||

| Van Kerrebroeck 2007 | 108 | 106.5236 | 59 | 40 | 87.055 | 61 | 21.5 | 68.00 (33.13, 102.87) | |

| Wang 2011 b | 23 | 0 | 57 | 3 | 0 | 58 | Not estimable | ||

| Total (95% CI) | 283 | 269 | 100 | 61.85 (45.70, 78.00) | |||||

| Heterogeneity: χ 2 = 4.48, df = 2 ( p = 0.11); I 2 = 55% | |||||||||

| Test for overall effect: Z = 7.51 ( p < 0.00001) | |||||||||

a No standard deviation values.

b No standard deviation values.

CI = confidence interval; df = difference; SD = standard deviation.Table 2Effect of desmopressin (with dose titrated against response) on hours of undisturbed sleep

An RCT evaluated desmopressin (0.1 mg, 0.2 mg, or 0.4 mg, escalated according to response) in adults with ≥2 voids/night (LoE 1b) [10] . One hundred and twenty-seven patients (85 men) achieving >20% reduction in nocturnal diuresis entered a double-blind efficacy phase. More desmopressin-treated patients showed >50% reduction in nocturia (33% vs 11%), reduced mean number of nocturnal voids (39% vs 15%; absolute difference –0.84 voids/night), and duration of the first sleep.

Adult men ( n = 151) with ≥2 voids/night were studied for 3 wk, following a dose titration phase (LoE 1b) [11] . Nocturnal voids decreased from 3.0 to 1.7 on desmopressin (vs 3.2–2.7 on placebo), with 34% and 3% experiencing fewer than half the number of nocturnal voids, respectively. Mean duration of the first sleep period increased from 2.7 h to 4.5 h (vs 2.5–2.9 h). A fall in serum sodium level to <130 mmol/l was seen in 4% of patients. In a small short-term crossover study incorporating a dose-response titration, desmopressin was associated with a reduced nocturnal diuresis of 0.59 ml/min and fewer micturitions at night than for placebo (1.1 vs 1.7, p < 0.001; mean difference 0.59) [12] . Twenty-four-hour diuresis was unaffected. Another RCT looked at 60 men receiving 0.1-mg desmopressin or placebo for 8 wk (LoE 2b) [13] . Mean number of nocturia episodes reduced from 2.6 to 1.6 (vs placebo 2.5 to 2.3).

Antidiuretic therapy adverse effects are summarized in Table 3 . The key adverse event of hyponatremia (< 125 mmols/l), while rare, means that baseline sodium level (< 130 mmols/l) was a selection criterion in research studies, and accordingly review of sodium levels is essential during treatment. An RCT of 115 men older than 65 yr with nocturia and nocturnal polyuria compared placebo with nontitrated 0.1 mg desmopressin (LoE 1b) [14] , showing decreased nocturnal urine output and number of nocturia episodes ( p < 0.01). The authors stated that long-term desmopressin might induce hyponatremia gradually, but specific data provided was limited.

| Study | Fu et al [43] | Mattiasson et al [11] | Van Kerrebroek et al [10] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients exposed ( n ) | 122 | 224 | 184 |

| Total AE, n (%) | 62 (50) | 107 (48) | 93 (51) |

| Serious AE | 3 (3) | 1 (<1) | 3 (2) |

| Deaths | 0 | 1 (<1) a | NR |

| AE related to study medication | 37 (39) | 60 (27) | 52 (28) |

| Headache | 10 (8) | 26 (12) | 17 (9) |

| Nausea | 5 (4) | 10 (4) | NR |

| Hyponatremia | 3 (3) | 8 (4) | 6 (3) |

| Abdominal pain | NR | NR | 8 (4) |

| Dry mouth | NR | NR | 5 (3) |

| Micturition frequency | 0 | NR | NR |

| Dizziness | 6 (5) | NR | 1 (1) |

| Fatigue | NR | NR | NR |

| Peripheral edema | NR | NR | NR |

| Hypertension | 4 (3) | NR | 3 (2) |

| Diarrhea | NR | 9 (4) | NR |

| Insomnia | NR | NR | 3 (2) |

| Diplopia | NR | NR | 1 (<1) |

| Depression | NR | NR | 1 (<1) |

a Unlikely to be study related (exacerbation of chronic lung disease).

NR = not reported.Table 3Adverse effects (AEs) during desmopressin treatment, in studies where dose titration was undertaken

Options for formulation and reduced dose level have been further investigated. A 4-wk placebo-controlled exploratory study described outcomes with low doses (10–100 μg) of desmopressin in 757 people (55% men; LoE 1b) [15] . Nocturia severity was around 3 episodes/night, and 90% of patients had nocturnal polyuria. Increasing doses of desmopressin were associated with decreasing numbers of nocturnal voids and voided volume, greater responder rates, and increased first sleep period duration. Reductions in serum sodium to <125 mmol/l occurred in two men taking 100 μg desmopressin. A 3-mo RCT reported on desmopressin orally disintegrating tablets or placebo in 385 men with ≥2 nocturnal voids (LoE 1b) [16] . Fifty micrograms (–0.37) and 75 μg (–0.41) desmopressin reduced the number of nocturnal voids, and increased the time to first void by approximately 40 min. Two patients on 50 μg desmopressin and nine on 75 μg developed a serum sodium level <130 mmol/l. A separate study in Japan reported similar findings (LoE 1b) [17] .

Intranasal administration was trialed in 20 men with nocturnal polyuria in a short-term cross-over RCT comparing placebo or 20 μg desmopressin, followed by an open period with 40 μg desmopressin (LoE1b) [18] . Desmopressin reduced nocturnal urine volume and the percentage of urine passed at night. However, the reduction in nocturnal frequency was only significant during unblinded treatment with 40 μg desmopressin.

An 8-wk study assessed tamsulosin (oral controlled absorption system formulation) in men (aged > 45 yr, International Prostate Symptom Score [IPSS] > 13, maximum flow rate 4–12 ml/s, and > 2 nocturnal voids; LoE 1b) [19] . The mean increase in hours of undisturbed sleep was 60 min for placebo and 82 min for tamsulosin ( p = 0.198). The mean reduction in nocturnal voids was –1.1 for tamsulosin (–0.7 for placebo, p = 0.099). The mean reduction in IPSS was 8.0 for tamsulosin (vs 5.6, p = 0.0099). Eight treatment-emergent adverse events were reported with tamsulosin, 10 with placebo.

Several studies used α-adrenergic blockade as comparator arms, and these are summarized in Table 4 . One study randomized 31 men with benign prostate enlargement (BPE) and nocturia ≥3/night to 2 mg doxazosin for 2 wk increasing to 4 mg, versus 20 μg intranasal desmopressin [20] . In the doxazosin group, nocturia reduced from 3.2/night to 1.2/night, versus 3.4–1.5 for desmopressin. Improvements in nocturia, quality of life and peak flow rates were not significantly different, while change in IPSS was better in the doxazosin group. Another trial randomized men to receive either naftopidil 50 mg or tamsulosin 0.2 mg (LoE 2b) [21] . At 2 wk, patients on naftopidil significantly improved their nocturia score, but at 8 wk the results were comparable between the two arms.

| Study description | Results | Outcome | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comparator | Tamsulosin | |||||||||||

| Author (yr) | Comparator | Main study inclusion criteria | Study duration | Randomized patients | Mean age ± SD (range) | Total no. patients ( N ) | Mean difference (before and after intervention; SD) | Mean age ± SD (range) | Total no. patients ( N ) | Mean difference (before and after intervention; SD) | Mean difference IV, fixed, 95% CI | |

| Yee 2015, [9] | Weight reduction + a-blocker vs a-blocker | Men ≥50, BPH/LUTS, BMI 25–35 kg/m 2 | 12 mo | 130 | 66.5 ± 6.9 (NA) | 60 | –0.1, 0.3 | 63.3 ± 7.8 (NA) | 57 | –0.1, 0.3 | 0.0 (–0.11, 0.11) | No difference |

| Simaioforidis 2011, [24] | Tamsulosin vs TUR-P | Nocturia for at least 12 mo and moderate to severe LUTS | 12 mo | 66 | 69.8 ± 7.9 (53–81) | 33 | –1, 0.2 | 67.5 ± 7.1 (52–78) | 33 | –0.2, 0.2 | –0.84 (–0.93, –0.75) | TUR-P appears superior to tamsulosin for BPH related nocturia |

| Gorgel, 2013, [46] | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg + meloxicam 15 mg vs tamsulosin 0.4 mg | Men ≥50, BPH/LUTS, IPSS:8–19, Qmax 5–15 ml/s | 3 mo | 400 | 61.4 ± 7.5 (NA) | 200 | –2.7, 0.6 | 63.3 ± 6.6 (NA) | 200 | –1.4, 0.4 | –1.3 (–1.4, –1.2) | Combination improves sleep quality |

| Oelke 2012, [39] | Tadalafil 5 mg vs tamsulosin 0.4 mg | Men ≥45, BPH/LUTS, IPSS ≥13, Qmax 4–15 ml/s | 12 wk | 339 | 63.5 ± NA (45–83) | 171 | –0.5, 0.1 | 63.5 ± NA (45–84) | 167 | –0.5, 0.1 | 0.0 (–0.02, 0.2) | No difference |

| Chapple 2011, [23] | Silodosin 8 mg vs tamsulosin 0.4 mg | Men ≥50, BPH/LUTS, IPSS ≥13, Qmax 4–15 ml/s | 12 wk | 955 | 65.8 ± 7.7 (50–87) | 371 | –0.9, NA | 66 ± 7.4 (50–81) | 376 | –0.8 | Not estimable | Silodosin is superior to placebo only |

| Ukimura 2008, [21] | Naftopidil 50 mg vs tamsulosin 0.2 mg | Men ≥50 yr, BPH, OAB, nocturia ≥2, flow rate <15 ml/s | 6–8 wk | 59 | 69.6 ± 6.8 (NA) | 25 | –3.8, 0.2 | 68.8 ± 8.2 (NA) | 23 | –3.1, 0.1 | –0.7 (–0.79, –0.61) | Early improvement (2 wk) in naftopidil arm but results are comparable at 8 wk |

| Ichihara 2014 [26] | Mirabegron + tamsulosin 0.2 mg vs tamsulosin 0.2 mg | BPH, OAB | 8 wk | 96 | 75.9 ± 7.5 (NA) | 38 | –0.47, 0.1 | 73.1 ± 8.7 (NA) | 38 | –0.16, 0.1 | –0.31 (–0.35, –0.27) | The combination is not superior to monotherapy (IPSS Q7) |

| Ahmed 2015, [25] | Desmopressin + tamsulosin vs tamsulosin 0.4 mg | Men ≥50 yr, BPH, LUTS, nocturia ≥2 | 3 mo | 248 | 70.1 ± 9.3 (NA) | 123 | –1.96, 0.2 | 68.6 ± 10.5 (NA) | 125 | –1.4, 0.1 | –0.55 (–0.58, –0.52) | The combination improves nocturnal frequency and first sleep period |

| Data modified for the purposes of the table. | ||||||||||||

Table 4Randomized controlled trials comparing drug therapy against tamsulosin for nocturia

A post-hoc subgroup analysis of three pooled studies using silodosin 8 mg in men with LUTS looked at responses to Question 7 of the IPSS (“How many times did you typically get up at night to urinate?”; LoE 1b) [22] . More men treated with silodosin reported nocturia improvement (53% vs 43%, p < 0.0001) and fewer patients worsening (9% vs 14%, p < 0.0001). In men with >2 nocturnal voids at baseline, 61% and 49% of patients with silodosin and placebo had reductions of >1 voids/ night, respectively ( p = 0.0003). A multicenter 12-wk trial randomized men to receive silodosin, tamsulosin, or placebo and found that only silodosin significantly reduced nocturia versus placebo ( p = 0.013) and the change from baseline was –0.9, –0.8, and –0.7 for silodosin, tamsulosin, and placebo, respectively (LoE 1b) [23] .

An RCT compared tamsulosin versus TURP for nocturia in 66 men with LUTS suggestive of BPE and no other predisposing factors for nocturia (LoE 2b) [24] . Both tamsulosin and TURP improved nocturia, with a greater response seen with TURP in the number of nocturnal awakenings and in symptom scores.

The combination of desmopressin and tamsulosin is superior to tamsulosin alone, since it reduces nocturnal frequency (–1.96 vs –1.41) and increases the first period of sleep (77.9 min vs 40.6 min), respectively (LoE 2b) [25] . The add-on of mirabegron to tamsulosin significantly improved IPSS Question 7 score from baseline compared with tamsulosin monotherapy (–0.47 vs –0.16, respectively; LoE 2b) [26] . Evidence from the CombAT study suggests that the combination of dutasteride and tamsulosin is more efficient at reducing nocturia score compared with tamsulosin monotherapy (LoE 1b) [27] .

Headache is the most frequent adverse event with tamsulosin therapy (3.2–5.5%). Dry ejaculation is more common with silodosin than tamsulosin or placebo (14.2% vs 2.1% vs 1.1%, respectively, p < 0.001).

A post-hoc analysis of two 12-wk RCTs of tolterodine 4-mg extended release, evaluated 745 men with 2.5 or more nocturia episodes/night, using a 7-d diary capturing urgency scores for each void (LoE 1b) [28] . Tolterodine significantly reduced the weekly values for night-time severe OAB micturitions. Adverse events showed a higher incidence of dry mouth for tolterodine (11% vs 4%). Using bladder diaries in which each void was attributed as “non-OAB” or OAB, another study randomized tolterodine extended release 4 mg against placebo (LoE 1b) [29] . Tolterodine reduced OAB-related nocturnal micturitions, but not the total nocturnal micturitions.

A 3-mo RCT of 963 adults with OAB evaluated fesoterodine flexible dosing for nocturnal urgency (≥ 2/night; LoE 1b) [30] . Change in mean number of nocturnal urgency episodes (−1.28 vs −1.07) and nocturnal micturitions (–1.02 vs –0.85) was greater with fesoterodine than placebo. A separate post-hoc analysis of a 12-wk RCT studied 555 Asian adults with ≥2 nocturia, ≥8 voiding, and ≥1 urgency urinary incontinence episodes/24 h (LoE 2b) [31] . Reductions in nocturia were not significantly different (fesoterodine 4 mg –0.63, 8 mg –0.77, vs placebo –0.56). When patients with a nocturnal polyuria index >33% were excluded, the decrease in nocturia was significantly greater with fesoterodine 8 mg verus placebo. Increases in nocturnal voided volume/micturition were greater with fesoterodine 4 (+38 ml) and 8 mg (+42 ml) than placebo (+15 ml).

Subgroup analysis of data from an RCT of Japanese OAB patients, showed solifenacin 10 mg decreased nocturia by 0.46 episodes (LoE 2b) [32] . Solifenacin 5 mg and 10 mg increased night-time volume voided per micturition by 30 ml and 41 ml ( p = 0.0033 and p < 0.0001, respectively).

Propiverine was not superior to placebo in reducing nocturia frequency ( p = 0.471; LoE 1b) [33] . Similar results were seen from another placebo controlled trial which compared propiverine versus solifenacin (LoE 1b) [34] . Only solifenacin 10 mg resulted in statistically significant reductions in the number of nocturia episodes versus placebo ( p = 0.021).

Adverse events attributable to antimuscarinic medications (eg, dry mucous membranes, constipation, gastro-esophageal reflux) have been extensively reported in OAB, and there is no suggestion that they differ in a population of patients with nocturia.

Data from a phase 2 dose-ranging study of mirabegron in a mixed population with OAB, showed that mirabegron 50 mg reduced nocturia episodes by 0.6 from baseline (vs 0.22 on placebo, p < 0.05; LoE 1b) [35] . Adverse events attributable to mirabegron (eg, hypertension) have been reported in OAB studies.

Pooled data from dutasteride phase 3 studies looking at results of IPSS Question 7 has been reported for 4321 patients (LoE 1b) [36] . Improvements in overall nocturia parameters were superior with dutasteride versus placebo from 12 mo onwards. The largest treatment group differences were seen in patients with a baseline nocturia score of 2 or 3.

A post-hoc subgroup analysis of self-reported nocturia in the Medical Therapy of Prostatic Symptoms trial of men with LUTS (LoE 1b) [37] found mean nocturia was reduced by –0.35, –0.40, –0.54, and –0.58 in the placebo, finasteride, doxazosin, and combination groups at 1 yr. Reductions with doxazosin and combination therapy, but not finasteride, were greater than with placebo at 1 yr and 4 yr.

A secondary analysis of the Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Program Trial reported on 1078 men (LoE 2b) [38] . From a baseline mean of 2.5, nocturia decreased to 1.8, 2.1, 2.0, and 2.1 in the terazosin, finasteride, combination, and placebo groups, respectively. Of men with ≥2 episodes of nocturia, 50% reduction was seen in 39%, 25%, 32%, and 22%.

Adverse events attributable to 5-α reductase inhibitors (eg, reduced ejaculate volume and effects on prostate-specific antigen) have been extensively reported in male voiding LUTS patients, and there is no suggestion that they differ in a population of patients with nocturia.

Separately, individual studies using tadalafil did not show significant improvement in nocturia. An analysis of four registrational RCTs of tadalafil for LUTS evaluated pooled responses to IPSS Question 7 (LoE 1b) [39] . Overall severity of nocturia was 2.3 ± 1.2, and the mean treatment change was –0.4 with placebo and –0.5 with tadalafil. Improved nocturnal frequency was seen in 47.5% on tadalafil (41.3% with placebo), and worse in 11.5% (vs 13.9%), which was not considered clinically meaningful.

Adverse events attributable to PDE5 inhibitors have been extensively reported in erectile dysfunction patients, and there is no suggestion that they differ in a population of patients with nocturia.

Administration of a diuretic in the afternoon has been proposed to reduce salt and water load in the body prior to bedtime. A double blind RCT compared diuretic therapy (azosemide 60 mg) against diazepam (5 mg) in 51 patients (47 men) with nocturia ≥3/night and no daytime urological problems (LoE 2b) [40] . For people with a higher atrial natriuretic peptide at baseline, daytime diuretic decreased the nocturnal frequency. Diazepam decreased nocturia in 22 out of 29 patients.

The efficacy of 1 mg bumetanide was evaluated in an RCT of 28 patients (15 men) in general practice (LoE 2b) [41] . During the placebo period the weekly number of nocturia episodes was 13.8 and during bumetanide treatment the number was reduced by 3.8. Ten men with BPE did not improve with bumetanide.

An RCT of 49 men with nocturnal polyuria evaluated furosemide 40 mg given 6 h before sleep (LoE 1b) [42] , yielding a decrease of 0.5 voids/night, versus 0 for placebo.

Another study reported a strategy of furosemide and desmopressin for nocturia (≥ 2 voids/night) in the elderly (LoE 1b) [43] . Eighty-two patients (58 men) were randomized to receive furosemide (20 mg, 6 h before bedtime) and the individual's optimal dose of desmopressin (at bedtime) or placebo for 3 wk. Reduced nocturnal voids (3.5 vs 2.0, p < 0.01) and urine volume (920 ml vs 584 ml, p < 0.01) were observed with active treatment.

Some diuretics work by causing natriuresis, and hence may be contraindicated in patients with hyponatremia, or at risk of acquiring it.

Diclofenac taken in the late evening was evaluated in nocturnal polyuria [44] . Twenty-six patients (20 men, mean age 72 yr) received 2 wk of placebo or active medication, crossing-over following a 1-wk rest period. Nocturia decreased from 2.7 to 2.3 ( p < 0.004). An RCT of celecoxib 100 mg versus placebo was undertaken in 80 men with BPE and ≥2 nocturia/night (LoE 1b) [45] . In the celecoxib group, mean nocturnal frequency decreased from 5.2 to 2.5 compared with 5.3 to 5.1. No significant side effects were reported in either study.

Tamsulosin (0.4 mg) alone or combined with meloxicam (15 mg), have been compared in 400 men with LUTS and nocturia (LoE 1b) [46] . Total IPSS, IPSS-Quality of Life, nocturia, and sleep quality score were significantly lower with combination therapy. A RCT randomized 40 men to loxoprofen, α-blocker, and 5-α-reductase inhibitors (vs α-blocker and 5-α-reductase inhibitors; LoE 2b) [47] . The group receiving the combination including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) experienced a greater reduction in nocturia (–1.5 ± 0.9 vs –1.1 ± 0.9, p = 0.034), but with a higher incidence of gastrointestinal side effects. Gastric discomfort with loxoprofen was seen in 12.5%, as compared with 2.6% of the control group.

An 8-wk placebo-controlled RCT looked at SagaPro (SagaMedica, Reykjavik, Iceland), a product derived from Angelica archangelica leaf, in 69 men with ≥2 nocturnal voids (LoE 1b) [48] . The study found no significant difference between the treatment groups, except on post-hoc subgroup analysis. In a crossover trial of furosemide and gosha-jinki-gan, 36 patients were reported to have improved symptom score, quality of life, nocturnal frequency, and hours of undisturbed sleep with both medications (LoE 2b) [49] .

A crossover RCT of 20 men with bladder outflow obstruction and nocturia (mean 3.1/night) compared 2 mg melatonin with placebo (LoE 1b) [50] . Melatonin and placebo caused a decrease in nocturia of 0.32 and 0.05 episodes/night ( p = 0.07). Nocturia responder rates (a mean reduction of at least –0.5 episodes/night) were higher with active medication ( p = 0.04). Daytime urinary frequency and IPSS were minimally altered.

A summary of the effect of medical therapy, excluding antidiuretic, on nocturia is given in Table 5 . Risk of bias summary for all treatments is given in Figure 2 , and a table for individual studies is given in Supplementary data. Recommendations from the European Association of Urology Guidelines panel for Nonneurogenic Male LUTS are given in Table 6 .

| Study description | Results | Outcome | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active medication | Placebo | |||||||||||

| Author, yr | Active medication | Main inclusion criteria | Study duration | Randomized patients, men (%) vs women (%) | Mean age ± SD (range) | Total no. patients ( N ) | Mean difference (before and after intervention), SD | Mean age ± SD (range) | Total no. patients ( N ) | Mean difference (before and after intervention), SD | Mean difference IV, fixed, 95% CI | |

| Djavan 2005, [19] | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg | Men >45, IPSS >13, flow rate 4–12 ml/s and >2 nocturnal voids | 8 wk | 117 men 117, (100), women, (0) | 66.8 ± 8.5 (NA) | 60 | –1.1, NA | 67.6 ± 7.6, (NA) |

56 | –0.7, NA | Not estimable | Tamsulosin reduces nocturnal frequency and increase the hours of undisturbed sleep |

| Oelke 2014, [39] | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg | Men ≥45, BPH, LUTS duration >6 mo, IPSS ≥13, max flow rate 4–15 ml/s | 12 wk | 340, men 340, (100), women, (0) | 63.5 ± NA 45–84) | 165 | –0.5, 0.1 | 63.7 ± NA, (46–89) |

172 | –0.3, 0.1 | –0.20, (–0.22, –0.18) |

Not significant improvement in nocturnal frequency with tamsulosin over placebo |

| Oelke 2014, [39] | Tadalafil 5 mg OD | Men ≥45, BPH, LUTS duration >6 mo, IPSS ≥13, max flow rate 4–15 ml/s | 12 wk | 343, men 343, (100), women, (0) | 63.5 ± NA (45–83) | 171 | –0.5, 0.1 | 63.7 ± NA, (46–89) |

172 | –0.3, 0.1 | Not estimable | Not clinically meaningful improvement in nocturnal frequency with tadalafil over placebo |

| Yokoyama 2011, [32] | Solifenacin 5 mg | Age ≥20, at least 1 nocturia episode | 12 wk | 653, men 111, (17) women 542, (83) |

61.8 ± 12.6 (NA) | 321 | –0.42, 1.5 | 61.5 ± 12.2, (NA) |

332 | –0.34, 1.4 | –0.08, (–0.31, 0.15) |

Solifenacin 5 mg increases nighttime volume voided per micturition |

| Yokoyama 2011, [32] | Solifenacin 10 mg | Age ≥20, At least 1 nocturia episode | 12 wk | 641, men 96, (15) women 545, (85) |

60.6 ± 12.6 (NA) | 309 | –0.46, 1.4 | 61.5 ± 12.2, (NA) |

332 | –0.34, 1.4 | –0.12, (–0.34, 0.10) |

Solifenacin 10 mg decreases nocturia episodes. It increases nighttime volume voided per micturition |

| Sigurdsson 2013, [48] | SagaPro | Men, age ≥45, nocturia ≥? | 8 wk | 66, men 66, (100) women (0) |

66.3 ± NA (49–86) | 31 | –0.83, 0.1 | 67.4 ± NA, (47–85) |

35 | –0.81, 0.3 | –0.02, (–0.12, 0.08) |

No difference between treatment arms |

| Yamaguchi 2007, [34] | Propiverine 20 mg | Age ≥20, OAB symptoms | 12 wk | 779 a , men 125, (16.1) women 654 (83.9) |

59.6 ± 13.6 (23–94) | 348 | –0.43, 1.2 | 60.8 ± 13.3, (20–89) |

361 | –0.3, 0.9 | –0.13, (–0.29, 0.03) |

Propiverine is not superior to placebo in controlling nocturnal frequency |

| Yamaguchi 2007, [34] | Solifenacin 5 mg | Age ≥20, OAB symptoms | 12 wk | 778 a , men 127, (16.3) women 651 (83.7) |

60.4 ± 13.3 (20–89) | 344 | –0.43, 1.2 | 60.8 ± 13.3, (20–89) |

361 | –0.3, 0.9 | –0.13, (–0.29, 0.03) |

Solifenacin 5 mg is not superior to placebo |

| Yamaguchi 2007, [34] | Solifenacin 10 mg | Age ≥20, OAB symptoms | 12 wk | 766 a , men 115, (15) women 651 (85) |

59.9 ± 13.0 (20–86) | 334 | –0.46, 0.9 | 60.8 ± 13.3, (20–89) |

3.61 | –0.3, 0.9 | –0.16, (–0.29, –0.03) |

Solifenacin 5 mg is superior to placebo |

| Gotoh 2011, [33] | Propiverine 20 mg | Age ≥18, OAB symptoms | 12 wk | 554, men 131, (23.6) women 423 (76.4) |

56.6 ± 13.6 (23–85) | 284 | –0.29, 0.6 | 58.7 ± 14.1, (21–93) |

270 | –0.25, 0.7 | –0.04, (–0.15, 0.07) |

No significant statistical improvement in nocturnal frequency |

| Chaple 2013, [35] | Mirabegron 25 mg | Age ≥18, OAB symptoms ≥3 mo, ≥3 urgency episodes | 12 wk | 333 a , men 35, (10.5) women 298, (89.5) |

57.2 ± 12.1 (NA) | 145 | –0.52, 1.3 | 57.1 ± 12.9, (NA) |

144 | –0.44, 1.1 | –0.08, (–0.36, 0.2) |

Mirabegron 25 mg is not superior to placebo |

| Chaple 2013, [35] | Mirabegron 50 mg | Age ≥18, OAB symptoms ≥3 mo, ≥3 urgency episodes | 12 wk | 333 a , men 33, (10) women 300, (90) |

56.9 ± 12.5 (NA) | 142 | –0.6, 1.3 | 57.1 ± 12.9, (NA) |

144 | –0.44, 1.1 | –0.16, (–0.44, 0.12) |

Mirabegron 50 mg is superior to placebo |

| Chaple 2013, [35] | Mirabegron 100 mg | Age ≥18, OAB symptoms ≥3 mo, ≥3 urgency episodes | 12 wk | 334 a , men 32, (9.5) women 302, (90.5) |

57.1 ± 12.5 (NA) | 141 | –0.42, 1.3 | 57.1 ± 12.9, (NA) |

144 | –0.44, 1.1 | 0.02, (–0.26, 0.30) |

Mirabegron 100 mg is not superior to placebo |

| Chaple 2013, [35] | Mirabegron 200 mg | Age ≥18, OAB symptoms ≥3 mo, ≥3 urgency episodes | 12 wk | 332 a , men 27, (8) women 305, (92) |

58.0 ± 13.7 (NA) | 147 | –0.59, 1.3 | 57.1 ± 12.9, (NA) |

144 | –0.44, 1.1 | –0.15, (–0.43, 0.13) |

Mirabegron 200 mg is not superior to placebo |

| Chaple 2013, [35] | Tolterodine ER 4 mg | Age ≥18, OAB symptoms ≥3 mo, ≥3 urgency episodes | 12 wk | 251 a , men 31, (12.4) women 220, (87.6) |

56.6 ± 12.8 (NA) | 72 | –0.59, 1.2 | 57.1 ± 12.9, (NA) |

144 | –0.44, 1.1 | –0.15, (–0.49, 0.19) |

Tolterodine ER 4 mg is not superior to placebo |

| Drake 2004, [50] | Melatonin 2 mg | Menwith IPSS Q7 score ≥3 | 4 wk | 20, men 20, (100) women (0) |

72.2± NA (60–81) | 19 | –0.3, 0.9 | 72.2 ± NA, (60–81) |

19 | –0.1, 0.1 | –0.20, (–0.61, 0.21) |

Melatonin significantly improves nocturia response rate |

| Reynard 1988, [42] | Furosemide 40 mg | Age ≥50, NP |

4 wk | 49, men 49, (100) women (0) |

70 ± NA (NA) | 23 | –0.5, na | 69 ± NA, (NA) |

20 | 0, NA | Not estimable | Furosemide improves nocturnal frequency in NP patients |

| Yokoyama 2014, [31] | Fesoterodine 4 mg | Nocturia ≥2, ≥8 voiding, ≥1 urgency episodes | 12 wk | 354 a , men 88, (25) women 266 (75) |

62.0 ± 13.5 (27–86) | 180 | –0.63, 1.42 | 59.7 ± 14, (27–88) | 174 | –0.56, 1.45 | –0.07, (–0.37, 0.23) |

Fesoterodine reduces nocturnal frequency |

| Yokoyama 2014, [31] | Fesoterodine 8 mg | Nocturia ≥2, ≥8 voiding, ≥1 urgency episodes | 12 wk | 375 a , men 90, (24) women 285 (76) |

60.6 ± 14 (20–87) | 201 | –0.77, 1.34 | 59.7 ± 14, (27–88) | 174 | –0.56, 1.45 | –0.07, (–0.37,0.23) |

Fesoterodine reduces nocturnal frequency |

| Oelke 2014, [36] | Dutasteride 0.5 mg | BPH, IPSS ≥12, PSA: 1.5–10, flow: ≤15 ml/s | 12 mo | 4244, men 4244, (100) women (0) |

NA | 2121 | –0.28, 0.04 | NA | 2123 | –0.11, 0.05 | –0.17, (–0.17, –0.17) |

Dutasteride improves nocturia outcomes based on IPSS Question 7 Score |

| Adla 2006, [44] | Diclofenac 50 mg | Nocturia ≥2, NP | 5 wk | 26, men 20, (77) women 6, (23) |

72 ± NA (52–90) | 26 | –0.5, 0.23 | 72 ± NA, (52–90) |

26 | –0.1, 0.23 | –0.40, (–0.53, –0.27) |

Diclofenac reduces mean nocturnal frequency |

| Falahaktar 2008, [45] | Celecoxib 100 mg | BPH, ≥2 voids per night, IPSS ≥8, NP excluded | 1 mo | 80, men 80, (100) women (0) |

64.3 ± 7.7 (49–80) | 40 | –2.67, 0.2 | 64.9 ± 7.05, (50–80) | 40 | –0.18, 0.5 | –2.49, (–2.66, –2.32) |

Celecoxib reduces mean nocturnal frequency |

| Cannon 1999, [18] | Desmopressin 20 μg | NP | 7 wk | 18, men 80, (100) women (0) |

70.5 ± NA (52–80) | 18 | –0.3, 0.45 | 70.5 ± NA, (52–80) |

18 | 0.1, 0.69 | –0.40, (–0.78, –0.02) |

Improvement in nocturnal volume. |

| Cannon 1999, [18] | Desmopressin 40 μg | NP | 7 wk | 18, men 18, (100) women (0) |

70.5 ± NA (52–80) | 18 | –0.7, 0.39 | 70.5 ± NA, (52–80) |

18 | 0.1, 0.69 | –0.8, (–1.16, –0.44) |

Improvement in nocturnal volume and nocturnal frequency |

a Data modified for the purposes of the table.

BPH = benign prostatic hyperplasia; CI = confidence interval; ER = extended release; IPSS = International Prostate Symptom Score; IV = independent variable; LUTS = lower urinary tract symptoms; NA = not available; NP = nocturnal polyuria; OAB = overactive bladder; SD = standard deviation.Table 5Effect on nocturnal voiding frequency of drug therapies compared against placebo

| LE | GR | |

|---|---|---|

| Treatment should aim to address underlying causative factors, which may be behavioral, systemic condition(s), sleep disorders, lower urinary tract dysfunction, or a combination of factors | 4 | A a |

| Lifestyle changes to reduce nocturnal urine volume and episodes of nocturia, and improve sleep quality should be discussed with the patient | 3 | A a |

| Desmopressin may be prescribed to decrease nocturia in men under the age of 65 yr. Screening for hyponatremia must be undertaken at baseline, during dose titration and during treatment | 1a | A |

| α-1 adrenergic antagonists may be offered to men with nocturia associated with lower urinary tract symptoms | 1b | B |

| Antimuscarinic drugs may be offered to men with nocturia associated with overactive bladder | 1b | B |

| 5α-Reductase inhibitors may be offered to men with nocturia who have moderate-to-severe LUTS and an enlarged prostate (> 40 ml) | 1b | C |

| PDE5 inhibitors should not be offered for the treatment of nocturia | 1b | B |

| A trial of timed diuretic therapy may be offered to men with nocturia due to nocturnal polyuria. Screening for hyponatremia should be undertaken at baseline and during treatment | 1b | C |

| Agents to promote sleep may be used to aid return to sleep in men with nocturia | 2 | C |

a Upgraded based on panel consensus.

GR = grade; LE = level of evidence; PDE5 = phosphodiesterase type 5.Table 6European Association of Urology Guidelines Panel for Non-neurogenic Male Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (LUTS) recommendations on medication treatment of nocturia in men

A detailed review of principal medical therapies of nocturia has been presented. It assumes that conservative measures are addressed as part of the care package. The nature of the reports included reflects the importance of several influences; the use of subjective or objective markers as primary outcomes, the range of severity included (twice per night being a commonly applied threshold), and the importance of subjective “bother.” The differences apparent in published literature in regards to populations, definitions, study design, outcome measures, and treatment durations represent a substantial limitation for the evidence base of nocturia therapy. In nocturia, some trials report an improvement which is reported as statistically significant, but which might actually be comparatively small, making the clinical relevance potentially marginal. In addition, the studies described generally take a pragmatic approach of measuring all nocturnal voids, which is somewhat different from the ICS definition, which focusses on patients who “wake at night to void.” Very little published evidence is available to signify what implications this could have for interpretation of results.

The review identified that antidiuretic therapy using clinician-directed dose titration was more effective than placebo in terms of reduced nocturnal voiding frequency and duration of undisturbed sleep. Nocturia severity improvement contributes to overall improvements in health-related quality of life [51] . The potential to worsen severity of the abnormality means that hyponatremia is a contraindication to antidiuretic therapy. Screening for hyponatremia must be undertaken at baseline, after initiation or dose titration and during treatment. The cumulative risk of hyponatremia over time is not clear, although evidence suggests that sodium imbalance may happen at any time during treatment. Three out of nine desmopressin studies included in this systematic review 10 11 12 undertook dose titration with the active treatment; this study design was to assign patients to the dose with treatment response and also for safety considerations. Clearly, a response selection phase will increase the likelihood of a positive outcome in the RCT and the associated effect sizes, since nonresponders will be excluded before the full trial. Nonetheless, dose titration is a process which can be undertaken in clinical practice in order to tailor therapy to individual patients, both in terms of efficacy and safety. Such a process adds to the burden on patients and healthcare providers in increasing the number of clinical contacts required.

Medications to treat LUTD in men (α-1 adrenergic antagonists, 5-α reductase inhibitors, PDE-5 inhibitor, phytotherapy) were not significantly better than placebo in short-term use. Data on OAB medications (antimuscarinics, beta-3 agonist) generally had a female-predominant population, and were also not significantly better than placebo in short-term use. It is an assumption that this would also apply in male-only populations, but no studies specifically addressing the impact of OAB medications on nocturia in men were identified. Subcategorizing the “OAB-related” nocturia episodes appeared to yield benefit for antimuscarinic therapy in one trial. Potential benefit was seen in long-term use in some studies using α-1 adrenergic antagonists and 5-α reductase inhibitors. Differences between therapies emerged in studies where α-1 adrenergic antagonist was the comparator. Benefits with combination therapies were not consistently observed. Other medications (diuretics, agents to promote sleep, NSAIDs), were sometimes reported as being associated with response or quality of life improvement. Nonetheless, additional research is needed to corroborate initial findings, particularly for therapies like NSAIDs, where the mechanism of action is uncertain.

The symptom of nocturia is an important one, since there may a significant medical cause, potentially an opportunity to screen for undiagnosed or suboptimally-managed disease, perhaps reduced incidence of severe complication, and potential economic benefits. Accordingly, clearly-relevant causes of nocturia that can be treated by mechanism-specific approaches, such as poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, or sleep apnoea, require direct intervention as the principal therapeutic priority. Since nocturia is a symptom rather than a disease, causative categories have been proposed [6] , and the diversity of the affected population is manifest. The range of potentially relevant contributors may well affect therapy outcome. Despite this, research populations often include diverse individuals, and may not undertake the full extent of evaluation needed to categorize factors likely to affect therapy response. However, the testing may limit the ability to deliver a trial, and may be unfeasible in routine clinical practice. The likelihood of developing a therapy that can be generalized appears remote, so nocturia therapy choice needs to consider the specific situation of individual patients. Accordingly, the studies need to be considered for analysis of responders, as well as the overall population response, since this may help develop improved approaches to clinical assessment in the future. Responder analysis is particularly interesting in studies reporting modest reductions in nocturia, which might be reported as statistically significant, but which are hard to perceive as clinically significant. In such a setting, responder analysis may help identify whether a subgroup did get a larger (clinically more useful) reduction in nocturia severity; predictors of response to enable targeting of therapy to individuals more likely to benefit would be a helpful advance.

Objective markers are scientifically preferable, but some studies have used patient perception (such as the IPSS Question 7), which is not uniformly consistent with objective markers. Furthermore, reported effect sizes are sometimes greater than perceived in clinical practice, so findings of many studies merit independent corroboration and follow up with real-life studies. Effect size is also likely to be affected by baseline severity, and this should be considered in the evaluation of trial outcomes. Finally, there is very little information on long-term outcomes of drug therapy for nocturia.

Author contributions: Marcus J. Drake had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Gravas, Drake, Sakalis, Karavitakis, Bach, Bosch, Gacci, Gratzke, Herrman, Madersbacher, Mamoulakis, Tikkinen.

Acquisition of data: Sakalis, Karavitakis, Bedretdinova.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Sakalis, Karavitakis, Drake, Gravas.

Drafting of the manuscript: Drake, Sakalis, Gravas.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Drake, Gravas, Bach, Bosch, Gacci, Gratzke, Herrman, Madersbacher, Mamoulakis, Tikkinen.

Statistical analysis: None.

Obtaining funding: None.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Bedretdinova.

Supervision: Gravas, Drake.

Other: None.

Financial disclosures: Marcus J. Drake certifies that all conflicts of interest, including specific financial interests and relationships and affiliations relevant to the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript (eg, employment/affiliation, grants or funding, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, royalties, or patents filed, received, or pending), are the following: Bach has received speaker honoraria from Cook Urology, Boston Scientific, GSK, and Richard Wolf, participates in a trial for Ipsen, and has received fellowships and travel grants from Lisa Laser; Drake has received speaker honoraria from Allergan, Astellas, and Ferring. He has received grants and research support from Allergan, Astellas, and Ferring; Gacci is a company consultant for Bayer, Ibsa, GSK, Lilly, Pfizer, and Pierre Frabre. He participates in trials for Bayer, Ibsa, and Lilly, and has received travel grants and research support from Bayer, GSK, and Lilly; Gratzke is a company consultant for Astellas Pharma, Bayer, Dendreon, Lilly, Rottapharm-Madaus, and Recordati. He has received speaker honoraria from AMS, Astellas Pharma, Pfizer, GSK, Steba, and Rottapharm-Madaus, and travel grants and research support from AMS, DFG, Bayer Healthcare Research, the EUSP, MSD, and Recordati; Maderbacher is a company consultant for Astellas, GSK, Lilly, and Takeda, and receives speaker honoraria from Astellas, Böhringer Ingelheim, GSK, Lilly, MSD, and Takeda. Mamoulakis is a company consultant for Astellas, GSK, and Teleflex, and has received speaker honoraria from Elli Lilly. He participates in trials for Astellas, Elli Lilly, Karl Storz Endoscope, and Medivation, and has received fellowships and travel grants from Ariti, Astellas, Boston Scientific, Cook Medical, GSK, Janssen, Karl Storz Endoscope, Porge-Coloplast, and Takeda. Gravas has received grants or research support from Pierre Fabre Medicament and GSK, travel grants from Angelini Pharma Hellas, Astellas, GSK, and Pierre Fabre Medicament, and speaker honoraria from Angelini Pharma Hellas, Pierre Fabre Medicament, Lilly, and GSK, and is a consultant for Astellas, Pierre Fabre Medicament, and GSK. Herrmann declares Karl Storz GmBH, honoraria, financial support for attending symposia, financial support for educational programs, consultancy, advisory, royalties: Boston Scientific AG honoraria, financial support for attending symposia, financial support for educational programs, consultancy, advisory Board; LISA Laser OHG AG Honoraria, financial support for attending symposia, financial support for educational programs; Ipsen Pharma Honoraria, financial support for attending symposia, advisory board; Bosch has received grants or research support from GSK and Astellas, speaker honoraria from GSK, AstraZeneca, Allergan, and FerringAG. He participates in trials for Astellas and is a consultant for Astellas, Eli-Lilly, and Ferring AG.

Funding/Support and role of the sponsor: None.

Nocturia is defined by the International Continence Society (ICS) as the complaint that an individual has to wake at night one or more times to void [1] . It reflects the relationship between the amount of urine produced while asleep, and the storage by the bladder of urine received. Nocturia can occur as part of lower urinary tract dysfunction (LUTD), notably in overactive bladder syndrome (OAB). Nocturia can also occur in association with other forms of LUTD, such as bladder outlet obstruction or chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Nocturia is a feature of systemic conditions affecting water and salt balance [2] , leading to excessive production of urine at all times (global polyuria) or primarily at night (nocturnal polyuria), so that nocturia can be a systemic symptom [3 4] . For example, cardiovascular, endocrine, and renal disease can affect water and salt homeostasis [5] , leading to increased rate of urine production.

Summarizing the causative categories for nocturia, the International Consultation on Male Lower Urinary Tract symptoms (LUTS) [6] listed:

Bladder storage problems;

24-h (global) polyuria (> 40 ml/kg urine output over a 24-h period);

Nocturnal polyuria (nocturnal output exceeding 20% of 24-h urine output in younger patients, or 33% of urine output in people aged over 65 yr [1] );

Sleep disorders;

Mixed etiology.

Thus, the treatment of nocturia is potentially complex, and was identified by the European Association of Urology Guidelines Panel for Male non-neurogenic LUTS as a key challenge. The aim of the current systematic review of treatment was to assess and compare available therapy options for nocturia, in terms of symptom severity and quality of life. The review focusses on men, in view of the differing lower urinary tract anatomy and medication options available compared with women.

The objectives were to determine the relative benefits and harms of treatment options for nocturia, and to perform subgroup and/or sensitivity analysis.

The Embase, Medline, Cochrane Systematic Reviews, and Cochrane Central (Cochrane Health Technology Assessment, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, Health Economics Evaluations Database) were searched with no restriction on date of publication (date of final search September 2016). The search strategy was registered on PROSPERO on October 21, 2015 ( http://dx.doi.org/10.15124/CRD42015027092 ). Comparative studies were included (randomized controlled trials [RCTs], and nonrandomized comparative studies [both prospective and retrospective, interventional, or observational]), studying adult men (male-only or mixed sex populations), with nocturia or nocturnal polyuria as a primary outcome, categorized within the following symptom groups:

Nocturia (ICS definition [7] , or as defined by trialist) as the primary presentation (ie, nocturia as the predominant bothersome symptom);

Nocturia as a secondary component of LUTS (ie, LUTS including nocturia);

Nocturnal polyuria (ICS definition [7] , or alternative definition if stated by the investigating group).

Interventions included: anticholinergics, mirabegron, α-blockers, 5-α reductase inhibitors, oral phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors, desmopressin, diuretics, sleep-promoting agents, and phytotherapy. Comparator controls were: no treatment, placebo, and alternative experimental treatment.

The primary outcomes were:

Symptom severity for nocturia (outcome measure defined as < 2 episodes, or cure [ie, no episodes of nocturia] or reduction in nocturia episodes, or as defined by trialist);

Quality of life for nocturia.

The secondary outcomes were:

Harms: adverse events of treatment and events leading to potential harm (eg, hyponatremia, voiding difficulties), withdrawal, or drop-out rates;

Any other outcomes judged relevant by reviewer.

Two review authors independently screened the titles and abstracts of identified records, and the full text of potentially eligible records was evaluated using a standardized form. Risk of bias was assessed, including: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other sources of bias. A list of potential confounders was developed a priori: age, sex, description of primary pathology, severity, or bother of nocturia.

Studies are summarized in Figure 1 .

Fig. 1

Systematic review flow chart.

DARE = Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects; HEED = Health Economic Evaluations Database; HTA = Health Technology Assessment; SR = systemic reviews.

One study investigated a behavioral modification program with desmopressin in comparison with desmopressin monotherapy in patients with nocturnal polyuria and nocturia (≥ 2 voids/night; Levels of Evidence [LoE] 1b) [8] . Nocturnal voids declined by –1.5 with combined therapy, compared with –1.2 on desmopressin alone (not significant). Another group randomized obese men with LUTS already on tamsulosin to receive a basic or a comprehensive weight reduction program (LoE 2b) [9] . The improvement in nocturia episodes was similar in both arms (–0.1 ± 0.9). Both studies showed mild adverse events only in pharmacotherapy-related arms.

The antidiuretic hormone arginine vasopressin increases renal water reabsorption and urinary osmolality. Antidiuretic therapy using the arginine vasopressin V2 receptor agonist desmopressin, with dose titration to achieve the best clinical response (as defined by the researchers in each study; including the dose to achieve either no voids per night, a decrease in nocturnal urine production of ≥ 20%, or nocturnal diuresis < 0.5 ml/min), was more effective than placebo in terms of reduced nocturnal voiding frequency ( Table 1 ) and duration of undisturbed sleep ( Table 2 ).

| Desmopressin | Placebo | Mean difference | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study or subgroup | Mean | SD | Total | Mean | SD | Total | Weight (%) | IV, fixed, 95% CI | |

| Asplung 1999 | –0.8 | 0.99 | 17 | –0.2 | 1.1 | 17 | 15.4 | –0.60 (-1.30, 0.1)] |  |

| Fu 2011 | –1.5 | 1.28 | 39 | –0.3 | 1.41 | 41 | 21.9 | –1.20 (-1.79, –0.61) | |

| Mattiasson 2002 | –1.3 | 1.25 | 81 | –0.5 | 1.75 | 62 | 28.8 | –0.80 (-1.31, –0.29) | |

| Rezakhanina 2011 a | –1 | 0 | 30 | –0.2 | 0 | 30 | Not estimable | ||

| Van Kerrebroeck 2007 | –1.25 | 1.35 | 59 | –0.4 | 1.29 | 61 | 34.4 | –0.85 (1.32, –0.38) | |

| Wang 2011 b | –1.5 | 0 | 57 | –0.8 | 0 | 58 | Not estimable | ||

| Total (95% CI) | 283 | 269 | 100 | –0.87 (–1.15, –0.60) | |||||

| Heterogeneity: χ 2 = 1.85, df = 3 ( p = 0.60); I 2 = 0% | |||||||||

| Test for overall effect: Z = 6.21 ( p < 0.00001) | |||||||||

a No standard deviation values.

b No standard deviation values.

CI = confidence interval; df = difference; SD = standard deviation.Table 1Effect of desmopressin (with dose titrated against response) on nocturnal voiding frequency

| Desmopressin | Placebo | Mean difference | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study or subgroup | Mean | SD | Total | Mean | SD | Total | Weight (%) | IV, fixed, 95% CI | |

| Asplung 1999 a | 102 | 0 | 17 | 18 | 0 | 17 | Not estimable |  |

|

| Fu 2011 | 69.6 | 52.798 | 39 | 23.7 | 50.434 | 41 | 50.9 | 45.90 (23.25, 68.55) | |

| Mattiasson 2002 | 110.4 | 102.71 | 81 | 24 | 84.483 | 62 | 27.7 | 86.40 (55.70, 117.10) | |

| Rezakhanina 2011 b | 120 | 0 | 30 | 30 | 0 | 30 | Not estimable | ||

| Van Kerrebroeck 2007 | 108 | 106.5236 | 59 | 40 | 87.055 | 61 | 21.5 | 68.00 (33.13, 102.87) | |

| Wang 2011 b | 23 | 0 | 57 | 3 | 0 | 58 | Not estimable | ||

| Total (95% CI) | 283 | 269 | 100 | 61.85 (45.70, 78.00) | |||||

| Heterogeneity: χ 2 = 4.48, df = 2 ( p = 0.11); I 2 = 55% | |||||||||

| Test for overall effect: Z = 7.51 ( p < 0.00001) | |||||||||

a No standard deviation values.

b No standard deviation values.

CI = confidence interval; df = difference; SD = standard deviation.Table 2Effect of desmopressin (with dose titrated against response) on hours of undisturbed sleep

An RCT evaluated desmopressin (0.1 mg, 0.2 mg, or 0.4 mg, escalated according to response) in adults with ≥2 voids/night (LoE 1b) [10] . One hundred and twenty-seven patients (85 men) achieving >20% reduction in nocturnal diuresis entered a double-blind efficacy phase. More desmopressin-treated patients showed >50% reduction in nocturia (33% vs 11%), reduced mean number of nocturnal voids (39% vs 15%; absolute difference –0.84 voids/night), and duration of the first sleep.

Adult men ( n = 151) with ≥2 voids/night were studied for 3 wk, following a dose titration phase (LoE 1b) [11] . Nocturnal voids decreased from 3.0 to 1.7 on desmopressin (vs 3.2–2.7 on placebo), with 34% and 3% experiencing fewer than half the number of nocturnal voids, respectively. Mean duration of the first sleep period increased from 2.7 h to 4.5 h (vs 2.5–2.9 h). A fall in serum sodium level to <130 mmol/l was seen in 4% of patients. In a small short-term crossover study incorporating a dose-response titration, desmopressin was associated with a reduced nocturnal diuresis of 0.59 ml/min and fewer micturitions at night than for placebo (1.1 vs 1.7, p < 0.001; mean difference 0.59) [12] . Twenty-four-hour diuresis was unaffected. Another RCT looked at 60 men receiving 0.1-mg desmopressin or placebo for 8 wk (LoE 2b) [13] . Mean number of nocturia episodes reduced from 2.6 to 1.6 (vs placebo 2.5 to 2.3).

Antidiuretic therapy adverse effects are summarized in Table 3 . The key adverse event of hyponatremia (< 125 mmols/l), while rare, means that baseline sodium level (< 130 mmols/l) was a selection criterion in research studies, and accordingly review of sodium levels is essential during treatment. An RCT of 115 men older than 65 yr with nocturia and nocturnal polyuria compared placebo with nontitrated 0.1 mg desmopressin (LoE 1b) [14] , showing decreased nocturnal urine output and number of nocturia episodes ( p < 0.01). The authors stated that long-term desmopressin might induce hyponatremia gradually, but specific data provided was limited.

| Study | Fu et al [43] | Mattiasson et al [11] | Van Kerrebroek et al [10] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients exposed ( n ) | 122 | 224 | 184 |

| Total AE, n (%) | 62 (50) | 107 (48) | 93 (51) |

| Serious AE | 3 (3) | 1 (<1) | 3 (2) |

| Deaths | 0 | 1 (<1) a | NR |

| AE related to study medication | 37 (39) | 60 (27) | 52 (28) |

| Headache | 10 (8) | 26 (12) | 17 (9) |

| Nausea | 5 (4) | 10 (4) | NR |

| Hyponatremia | 3 (3) | 8 (4) | 6 (3) |

| Abdominal pain | NR | NR | 8 (4) |

| Dry mouth | NR | NR | 5 (3) |

| Micturition frequency | 0 | NR | NR |

| Dizziness | 6 (5) | NR | 1 (1) |

| Fatigue | NR | NR | NR |

| Peripheral edema | NR | NR | NR |

| Hypertension | 4 (3) | NR | 3 (2) |

| Diarrhea | NR | 9 (4) | NR |

| Insomnia | NR | NR | 3 (2) |

| Diplopia | NR | NR | 1 (<1) |

| Depression | NR | NR | 1 (<1) |

a Unlikely to be study related (exacerbation of chronic lung disease).

NR = not reported.Table 3Adverse effects (AEs) during desmopressin treatment, in studies where dose titration was undertaken

Options for formulation and reduced dose level have been further investigated. A 4-wk placebo-controlled exploratory study described outcomes with low doses (10–100 μg) of desmopressin in 757 people (55% men; LoE 1b) [15] . Nocturia severity was around 3 episodes/night, and 90% of patients had nocturnal polyuria. Increasing doses of desmopressin were associated with decreasing numbers of nocturnal voids and voided volume, greater responder rates, and increased first sleep period duration. Reductions in serum sodium to <125 mmol/l occurred in two men taking 100 μg desmopressin. A 3-mo RCT reported on desmopressin orally disintegrating tablets or placebo in 385 men with ≥2 nocturnal voids (LoE 1b) [16] . Fifty micrograms (–0.37) and 75 μg (–0.41) desmopressin reduced the number of nocturnal voids, and increased the time to first void by approximately 40 min. Two patients on 50 μg desmopressin and nine on 75 μg developed a serum sodium level <130 mmol/l. A separate study in Japan reported similar findings (LoE 1b) [17] .

Intranasal administration was trialed in 20 men with nocturnal polyuria in a short-term cross-over RCT comparing placebo or 20 μg desmopressin, followed by an open period with 40 μg desmopressin (LoE1b) [18] . Desmopressin reduced nocturnal urine volume and the percentage of urine passed at night. However, the reduction in nocturnal frequency was only significant during unblinded treatment with 40 μg desmopressin.

An 8-wk study assessed tamsulosin (oral controlled absorption system formulation) in men (aged > 45 yr, International Prostate Symptom Score [IPSS] > 13, maximum flow rate 4–12 ml/s, and > 2 nocturnal voids; LoE 1b) [19] . The mean increase in hours of undisturbed sleep was 60 min for placebo and 82 min for tamsulosin ( p = 0.198). The mean reduction in nocturnal voids was –1.1 for tamsulosin (–0.7 for placebo, p = 0.099). The mean reduction in IPSS was 8.0 for tamsulosin (vs 5.6, p = 0.0099). Eight treatment-emergent adverse events were reported with tamsulosin, 10 with placebo.

Several studies used α-adrenergic blockade as comparator arms, and these are summarized in Table 4 . One study randomized 31 men with benign prostate enlargement (BPE) and nocturia ≥3/night to 2 mg doxazosin for 2 wk increasing to 4 mg, versus 20 μg intranasal desmopressin [20] . In the doxazosin group, nocturia reduced from 3.2/night to 1.2/night, versus 3.4–1.5 for desmopressin. Improvements in nocturia, quality of life and peak flow rates were not significantly different, while change in IPSS was better in the doxazosin group. Another trial randomized men to receive either naftopidil 50 mg or tamsulosin 0.2 mg (LoE 2b) [21] . At 2 wk, patients on naftopidil significantly improved their nocturia score, but at 8 wk the results were comparable between the two arms.

| Study description | Results | Outcome | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comparator | Tamsulosin | |||||||||||

| Author (yr) | Comparator | Main study inclusion criteria | Study duration | Randomized patients | Mean age ± SD (range) | Total no. patients ( N ) | Mean difference (before and after intervention; SD) | Mean age ± SD (range) | Total no. patients ( N ) | Mean difference (before and after intervention; SD) | Mean difference IV, fixed, 95% CI | |

| Yee 2015, [9] | Weight reduction + a-blocker vs a-blocker | Men ≥50, BPH/LUTS, BMI 25–35 kg/m 2 | 12 mo | 130 | 66.5 ± 6.9 (NA) | 60 | –0.1, 0.3 | 63.3 ± 7.8 (NA) | 57 | –0.1, 0.3 | 0.0 (–0.11, 0.11) | No difference |

| Simaioforidis 2011, [24] | Tamsulosin vs TUR-P | Nocturia for at least 12 mo and moderate to severe LUTS | 12 mo | 66 | 69.8 ± 7.9 (53–81) | 33 | –1, 0.2 | 67.5 ± 7.1 (52–78) | 33 | –0.2, 0.2 | –0.84 (–0.93, –0.75) | TUR-P appears superior to tamsulosin for BPH related nocturia |

| Gorgel, 2013, [46] | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg + meloxicam 15 mg vs tamsulosin 0.4 mg | Men ≥50, BPH/LUTS, IPSS:8–19, Qmax 5–15 ml/s | 3 mo | 400 | 61.4 ± 7.5 (NA) | 200 | –2.7, 0.6 | 63.3 ± 6.6 (NA) | 200 | –1.4, 0.4 | –1.3 (–1.4, –1.2) | Combination improves sleep quality |

| Oelke 2012, [39] | Tadalafil 5 mg vs tamsulosin 0.4 mg | Men ≥45, BPH/LUTS, IPSS ≥13, Qmax 4–15 ml/s | 12 wk | 339 | 63.5 ± NA (45–83) | 171 | –0.5, 0.1 | 63.5 ± NA (45–84) | 167 | –0.5, 0.1 | 0.0 (–0.02, 0.2) | No difference |

| Chapple 2011, [23] | Silodosin 8 mg vs tamsulosin 0.4 mg | Men ≥50, BPH/LUTS, IPSS ≥13, Qmax 4–15 ml/s | 12 wk | 955 | 65.8 ± 7.7 (50–87) | 371 | –0.9, NA | 66 ± 7.4 (50–81) | 376 | –0.8 | Not estimable | Silodosin is superior to placebo only |

| Ukimura 2008, [21] | Naftopidil 50 mg vs tamsulosin 0.2 mg | Men ≥50 yr, BPH, OAB, nocturia ≥2, flow rate <15 ml/s | 6–8 wk | 59 | 69.6 ± 6.8 (NA) | 25 | –3.8, 0.2 | 68.8 ± 8.2 (NA) | 23 | –3.1, 0.1 | –0.7 (–0.79, –0.61) | Early improvement (2 wk) in naftopidil arm but results are comparable at 8 wk |

| Ichihara 2014 [26] | Mirabegron + tamsulosin 0.2 mg vs tamsulosin 0.2 mg | BPH, OAB | 8 wk | 96 | 75.9 ± 7.5 (NA) | 38 | –0.47, 0.1 | 73.1 ± 8.7 (NA) | 38 | –0.16, 0.1 | –0.31 (–0.35, –0.27) | The combination is not superior to monotherapy (IPSS Q7) |

| Ahmed 2015, [25] | Desmopressin + tamsulosin vs tamsulosin 0.4 mg | Men ≥50 yr, BPH, LUTS, nocturia ≥2 | 3 mo | 248 | 70.1 ± 9.3 (NA) | 123 | –1.96, 0.2 | 68.6 ± 10.5 (NA) | 125 | –1.4, 0.1 | –0.55 (–0.58, –0.52) | The combination improves nocturnal frequency and first sleep period |

| Data modified for the purposes of the table. | ||||||||||||

Table 4Randomized controlled trials comparing drug therapy against tamsulosin for nocturia

A post-hoc subgroup analysis of three pooled studies using silodosin 8 mg in men with LUTS looked at responses to Question 7 of the IPSS (“How many times did you typically get up at night to urinate?”; LoE 1b) [22] . More men treated with silodosin reported nocturia improvement (53% vs 43%, p < 0.0001) and fewer patients worsening (9% vs 14%, p < 0.0001). In men with >2 nocturnal voids at baseline, 61% and 49% of patients with silodosin and placebo had reductions of >1 voids/ night, respectively ( p = 0.0003). A multicenter 12-wk trial randomized men to receive silodosin, tamsulosin, or placebo and found that only silodosin significantly reduced nocturia versus placebo ( p = 0.013) and the change from baseline was –0.9, –0.8, and –0.7 for silodosin, tamsulosin, and placebo, respectively (LoE 1b) [23] .

An RCT compared tamsulosin versus TURP for nocturia in 66 men with LUTS suggestive of BPE and no other predisposing factors for nocturia (LoE 2b) [24] . Both tamsulosin and TURP improved nocturia, with a greater response seen with TURP in the number of nocturnal awakenings and in symptom scores.

The combination of desmopressin and tamsulosin is superior to tamsulosin alone, since it reduces nocturnal frequency (–1.96 vs –1.41) and increases the first period of sleep (77.9 min vs 40.6 min), respectively (LoE 2b) [25] . The add-on of mirabegron to tamsulosin significantly improved IPSS Question 7 score from baseline compared with tamsulosin monotherapy (–0.47 vs –0.16, respectively; LoE 2b) [26] . Evidence from the CombAT study suggests that the combination of dutasteride and tamsulosin is more efficient at reducing nocturia score compared with tamsulosin monotherapy (LoE 1b) [27] .

Headache is the most frequent adverse event with tamsulosin therapy (3.2–5.5%). Dry ejaculation is more common with silodosin than tamsulosin or placebo (14.2% vs 2.1% vs 1.1%, respectively, p < 0.001).

A post-hoc analysis of two 12-wk RCTs of tolterodine 4-mg extended release, evaluated 745 men with 2.5 or more nocturia episodes/night, using a 7-d diary capturing urgency scores for each void (LoE 1b) [28] . Tolterodine significantly reduced the weekly values for night-time severe OAB micturitions. Adverse events showed a higher incidence of dry mouth for tolterodine (11% vs 4%). Using bladder diaries in which each void was attributed as “non-OAB” or OAB, another study randomized tolterodine extended release 4 mg against placebo (LoE 1b) [29] . Tolterodine reduced OAB-related nocturnal micturitions, but not the total nocturnal micturitions.

A 3-mo RCT of 963 adults with OAB evaluated fesoterodine flexible dosing for nocturnal urgency (≥ 2/night; LoE 1b) [30] . Change in mean number of nocturnal urgency episodes (−1.28 vs −1.07) and nocturnal micturitions (–1.02 vs –0.85) was greater with fesoterodine than placebo. A separate post-hoc analysis of a 12-wk RCT studied 555 Asian adults with ≥2 nocturia, ≥8 voiding, and ≥1 urgency urinary incontinence episodes/24 h (LoE 2b) [31] . Reductions in nocturia were not significantly different (fesoterodine 4 mg –0.63, 8 mg –0.77, vs placebo –0.56). When patients with a nocturnal polyuria index >33% were excluded, the decrease in nocturia was significantly greater with fesoterodine 8 mg verus placebo. Increases in nocturnal voided volume/micturition were greater with fesoterodine 4 (+38 ml) and 8 mg (+42 ml) than placebo (+15 ml).

Subgroup analysis of data from an RCT of Japanese OAB patients, showed solifenacin 10 mg decreased nocturia by 0.46 episodes (LoE 2b) [32] . Solifenacin 5 mg and 10 mg increased night-time volume voided per micturition by 30 ml and 41 ml ( p = 0.0033 and p < 0.0001, respectively).

Propiverine was not superior to placebo in reducing nocturia frequency ( p = 0.471; LoE 1b) [33] . Similar results were seen from another placebo controlled trial which compared propiverine versus solifenacin (LoE 1b) [34] . Only solifenacin 10 mg resulted in statistically significant reductions in the number of nocturia episodes versus placebo ( p = 0.021).

Adverse events attributable to antimuscarinic medications (eg, dry mucous membranes, constipation, gastro-esophageal reflux) have been extensively reported in OAB, and there is no suggestion that they differ in a population of patients with nocturia.

Data from a phase 2 dose-ranging study of mirabegron in a mixed population with OAB, showed that mirabegron 50 mg reduced nocturia episodes by 0.6 from baseline (vs 0.22 on placebo, p < 0.05; LoE 1b) [35] . Adverse events attributable to mirabegron (eg, hypertension) have been reported in OAB studies.

Pooled data from dutasteride phase 3 studies looking at results of IPSS Question 7 has been reported for 4321 patients (LoE 1b) [36] . Improvements in overall nocturia parameters were superior with dutasteride versus placebo from 12 mo onwards. The largest treatment group differences were seen in patients with a baseline nocturia score of 2 or 3.

A post-hoc subgroup analysis of self-reported nocturia in the Medical Therapy of Prostatic Symptoms trial of men with LUTS (LoE 1b) [37] found mean nocturia was reduced by –0.35, –0.40, –0.54, and –0.58 in the placebo, finasteride, doxazosin, and combination groups at 1 yr. Reductions with doxazosin and combination therapy, but not finasteride, were greater than with placebo at 1 yr and 4 yr.

A secondary analysis of the Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Program Trial reported on 1078 men (LoE 2b) [38] . From a baseline mean of 2.5, nocturia decreased to 1.8, 2.1, 2.0, and 2.1 in the terazosin, finasteride, combination, and placebo groups, respectively. Of men with ≥2 episodes of nocturia, 50% reduction was seen in 39%, 25%, 32%, and 22%.

Adverse events attributable to 5-α reductase inhibitors (eg, reduced ejaculate volume and effects on prostate-specific antigen) have been extensively reported in male voiding LUTS patients, and there is no suggestion that they differ in a population of patients with nocturia.

Separately, individual studies using tadalafil did not show significant improvement in nocturia. An analysis of four registrational RCTs of tadalafil for LUTS evaluated pooled responses to IPSS Question 7 (LoE 1b) [39] . Overall severity of nocturia was 2.3 ± 1.2, and the mean treatment change was –0.4 with placebo and –0.5 with tadalafil. Improved nocturnal frequency was seen in 47.5% on tadalafil (41.3% with placebo), and worse in 11.5% (vs 13.9%), which was not considered clinically meaningful.

Adverse events attributable to PDE5 inhibitors have been extensively reported in erectile dysfunction patients, and there is no suggestion that they differ in a population of patients with nocturia.

Administration of a diuretic in the afternoon has been proposed to reduce salt and water load in the body prior to bedtime. A double blind RCT compared diuretic therapy (azosemide 60 mg) against diazepam (5 mg) in 51 patients (47 men) with nocturia ≥3/night and no daytime urological problems (LoE 2b) [40] . For people with a higher atrial natriuretic peptide at baseline, daytime diuretic decreased the nocturnal frequency. Diazepam decreased nocturia in 22 out of 29 patients.

The efficacy of 1 mg bumetanide was evaluated in an RCT of 28 patients (15 men) in general practice (LoE 2b) [41] . During the placebo period the weekly number of nocturia episodes was 13.8 and during bumetanide treatment the number was reduced by 3.8. Ten men with BPE did not improve with bumetanide.

An RCT of 49 men with nocturnal polyuria evaluated furosemide 40 mg given 6 h before sleep (LoE 1b) [42] , yielding a decrease of 0.5 voids/night, versus 0 for placebo.

Another study reported a strategy of furosemide and desmopressin for nocturia (≥ 2 voids/night) in the elderly (LoE 1b) [43] . Eighty-two patients (58 men) were randomized to receive furosemide (20 mg, 6 h before bedtime) and the individual's optimal dose of desmopressin (at bedtime) or placebo for 3 wk. Reduced nocturnal voids (3.5 vs 2.0, p < 0.01) and urine volume (920 ml vs 584 ml, p < 0.01) were observed with active treatment.

Some diuretics work by causing natriuresis, and hence may be contraindicated in patients with hyponatremia, or at risk of acquiring it.

Diclofenac taken in the late evening was evaluated in nocturnal polyuria [44] . Twenty-six patients (20 men, mean age 72 yr) received 2 wk of placebo or active medication, crossing-over following a 1-wk rest period. Nocturia decreased from 2.7 to 2.3 ( p < 0.004). An RCT of celecoxib 100 mg versus placebo was undertaken in 80 men with BPE and ≥2 nocturia/night (LoE 1b) [45] . In the celecoxib group, mean nocturnal frequency decreased from 5.2 to 2.5 compared with 5.3 to 5.1. No significant side effects were reported in either study.

Tamsulosin (0.4 mg) alone or combined with meloxicam (15 mg), have been compared in 400 men with LUTS and nocturia (LoE 1b) [46] . Total IPSS, IPSS-Quality of Life, nocturia, and sleep quality score were significantly lower with combination therapy. A RCT randomized 40 men to loxoprofen, α-blocker, and 5-α-reductase inhibitors (vs α-blocker and 5-α-reductase inhibitors; LoE 2b) [47] . The group receiving the combination including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) experienced a greater reduction in nocturia (–1.5 ± 0.9 vs –1.1 ± 0.9, p = 0.034), but with a higher incidence of gastrointestinal side effects. Gastric discomfort with loxoprofen was seen in 12.5%, as compared with 2.6% of the control group.

An 8-wk placebo-controlled RCT looked at SagaPro (SagaMedica, Reykjavik, Iceland), a product derived from Angelica archangelica leaf, in 69 men with ≥2 nocturnal voids (LoE 1b) [48] . The study found no significant difference between the treatment groups, except on post-hoc subgroup analysis. In a crossover trial of furosemide and gosha-jinki-gan, 36 patients were reported to have improved symptom score, quality of life, nocturnal frequency, and hours of undisturbed sleep with both medications (LoE 2b) [49] .

A crossover RCT of 20 men with bladder outflow obstruction and nocturia (mean 3.1/night) compared 2 mg melatonin with placebo (LoE 1b) [50] . Melatonin and placebo caused a decrease in nocturia of 0.32 and 0.05 episodes/night ( p = 0.07). Nocturia responder rates (a mean reduction of at least –0.5 episodes/night) were higher with active medication ( p = 0.04). Daytime urinary frequency and IPSS were minimally altered.

A summary of the effect of medical therapy, excluding antidiuretic, on nocturia is given in Table 5 . Risk of bias summary for all treatments is given in Figure 2 , and a table for individual studies is given in Supplementary data. Recommendations from the European Association of Urology Guidelines panel for Nonneurogenic Male LUTS are given in Table 6 .

| Study description | Results | Outcome | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active medication | Placebo | |||||||||||

| Author, yr | Active medication | Main inclusion criteria | Study duration | Randomized patients, men (%) vs women (%) | Mean age ± SD (range) | Total no. patients ( N ) | Mean difference (before and after intervention), SD | Mean age ± SD (range) | Total no. patients ( N ) | Mean difference (before and after intervention), SD | Mean difference IV, fixed, 95% CI | |

| Djavan 2005, [19] | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg | Men >45, IPSS >13, flow rate 4–12 ml/s and >2 nocturnal voids | 8 wk | 117 men 117, (100), women, (0) | 66.8 ± 8.5 (NA) | 60 | –1.1, NA | 67.6 ± 7.6, (NA) |

56 | –0.7, NA | Not estimable | Tamsulosin reduces nocturnal frequency and increase the hours of undisturbed sleep |

| Oelke 2014, [39] | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg | Men ≥45, BPH, LUTS duration >6 mo, IPSS ≥13, max flow rate 4–15 ml/s | 12 wk | 340, men 340, (100), women, (0) | 63.5 ± NA 45–84) | 165 | –0.5, 0.1 | 63.7 ± NA, (46–89) |

172 | –0.3, 0.1 | –0.20, (–0.22, –0.18) |

Not significant improvement in nocturnal frequency with tamsulosin over placebo |